Hamish McRae: Watch what the G20 does over the next decade, not what politicians say

Economic Life: It is a somewhat sobering thought that Turkey and Indonesia will add more to global wealth over the next decade than Germany, France or Britain

Today and tomorrow the finance ministers and central banks of the Group of Twenty, the world of economics' new coordinating body – are meeting in Paris for one of their regular twice-a-year gatherings to ponder the direction of the recovery. There have been as usual the spate of briefings and leaks about their intentions, stories that I always feel should never be taken too seriously. What matters is what politicians do, not what they say.

There are, however, some pointers to the coming months, things to watch for that they might do or that might simply happen. At the heart of the matter is whether the present growth phase of the economy will encounter some sort of early-cycle pause and if so how serious might that be. I can see at least five huge unresolved issues that will, depending on how they are handled, determine whether there is such a pause. So what we should be looking for are hints about future policy on those issues. A word about each in a moment; first, a comment on the growth phase itself.

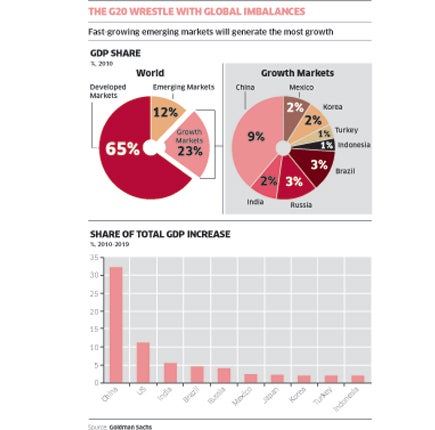

None of us can know how long the present expansion will last but it is reasonable to expect several years of solid growth. Previous growth phases have lasted seven-to-nine years. But the present phase will differ from previous ones as most of that growth will come from the fastest-growing and largest emerging economies. At the moment the developed world still accounts for 65 per cent of global GDP. Of the rest, a new paper by Goldman Sachs identifies a number of large emerging economies which it describes as the "growth markets". You can see them on the right hand of the two pie charts above. Look forward to 2020 and these markets will deliver most of the growth that will happen. As you can see from the bar charts, among the developed countries only the US will deliver a significant portion of global growth. Japan and Korea get on to the chart but no European country. It is a somewhat sobering thought that Turkey and Indonesia will add more to global wealth over the next decade than Germany, France or Britain.

But – and this is the crucial point – these countries will only be able to deliver that growth within a freely trading world economy. So what the G20 has to confront are the threats to that, threats that can be summed up under the general heading of global imbalances.

Issue one is the US fiscal deficit. We have just had the US budget for the coming fiscal year, the one that starts next October – we run our fiscal year April to April, they do it October to October. In his proposed budget, President Barack Obama projects that the deficit will come down from nearly 12 per cent of GDP to 7 per cent. That would actually be a slightly swifter decline than that proposed in the UK, so if it were achieved it would be a huge step forward. Unfortunately in subsequent years the pace for correcting the deficit eases back and the US is still planning to be running a deficit of 3 per cent of GDP in 2017. And of course this is only the President's plan and it will be changed by Congress. Quite which way it will be changed is far from clear and the big numbers of the decline are most ambitious.

Still, we will in a few months' time have some sort of feeling about how serious the US is in cutting its fiscal deficit and that will have a significant impact on one element of global imbalances. The savings imbalance, whereby Chinese savings finance the US deficit, is one destabilising element in the world economy. Though the link between the fiscal deficit and the current account deficit is a loose one, a narrowing of the former is an essential precondition for a narrowing of the latter.

But if debtors must take responsibility for their debts, creditors must take responsibility for their lending. Issue two is Chinese monetary and currency policy.

Here three things are happening. One is that the trade surplus is declining fast: it has halved in the past few months. The second is that inflation has become a serious problem in China and export prices are rising fast. And the final one is that monetary policy is being tightened at last and it would be consistent were China also to permit some further upward creep of the yuan/dollar exchange rate. As a result of all this, it is at least plausible that the trade imbalance between China and the rest of the world will decline in the coming months. In short, China's contribution to global imbalances will decline.

Issue three is European sovereign solvency. When will the first EU member state, presumably Greece, default? This is not the sort of question you ask in polite society, and my instinct is that default is still at least three years off. But it may be that the new Irish government's efforts, post the forthcoming election, to renegotiate its loan package, will trigger a reassessment of the dangers of a sovereign default – or you might even say, the need for a sovereign default. The financing needs of other much larger EU nations in the coming months are huge and we have to accept there will be further bail-outs. Things could become very difficult indeed.

Issue four is global energy and food production capacity. Already, very early in the growth phase of the cycle there is great pressure on the oil price and on food prices. If there is growth on the scale envisaged by Goldman Sachs over this decade, that pressure will remain, indeed grow, in the years to come. One of the things being talked about is the role of speculation in raising food and raw material prices. Would it were just that. Whatever the impact in the short-term – and I think it is pretty clear that the last spike in oil prices was indeed driven by speculation – in the long run it all evens out. So what will hold down prices will be the ability to increase capacity, difficult in the case of oil, and hold down demand, difficult in the face of rapid growth. Unfortunately it is not really within the scope of politicians to increase the supply of oil and raw materials, though I suppose they can by their actions decrease the supply.

Finally issue five, the fate of the dollar. The basic question here is how long the dollar retains its role as the global reserve currency. You will hear all sorts of guff about the replacement by something else, and at the head of that queue is the International Monetary Fund's Special Drawing Rights. But there is no point in talking about this if central banks, particularly the Chinese, go on buying dollars and sticking them in their reserves. Still, within the foreseeable future the dollar's role will decline, so what happens in the coming months may give us a clue to the speed of that decline.

Bit of a hodge-podge? Yup. That is an inevitable characteristic of these international meetings. But as I say, watch what they do, not what they say about those five issues noted above. Note too, where growth is coming from this decade, and how as a result the balance of power is changing.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies