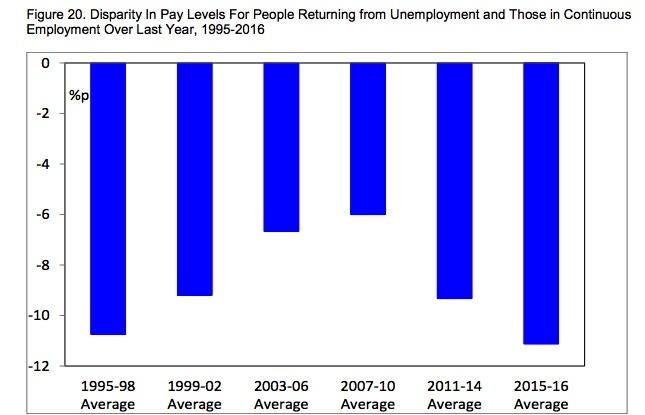

The chart that shows the cost of losing your job is at its highest for more than 20 years

The disparity in wage levels between people now in work but unemployed a year earlier and those in continuous employment is at its highest since the before the late 1990s

The financial cost of losing one's job has risen significantly, which is likely to be one of the reasons why workers have been unwilling to press employers for pay rises, one of the external members of the rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee of the Bank of England has argued.

In a speech to the Resolution Foundation think tank, Michael Saunders presented data which shows the disparity in wage levels between people now in work but unemployed a year earlier and those in continuous employment over that time has been rising.

The unemployment penalty

The 2015-16 wage gap was 11 per cent, which is higher than any period since before the late 1990s.

This was after making various adjustments for age, education, gender and occupation.

Mr Saunders also noted that unemployed people today are considerably less likely to claim the dole than they were 20 years ago (with a 50 per cent rate now versus an 80 per cent rate in the 1990s).

Mr Saunders, who joined the MPC from Citi, last year said this “wage scarring” effect, combined with a surge in self-employment and the numbers of people working in the so-called “gig economy”, was evidence of increased job insecurity in the UK labour market.

“Reduced job security and the greater financial cost of unemployment may reduce workers’ bargaining power and create higher risk aversion – making people more likely to settle for modest or no wage growth and continued employment, rather than push for higher wage growth if that comes with risks of job losses,” he said.

The Bank has been puzzling over the fact that the headline unemployment rate currently stands at just 4.8 per cent – close to historic lows – but average wage inflation still remains well below pre-crisis levels, with little sign of workers demanding higher wages.

A tighter employment market is normally associated with higher wage inflation and also consumer price inflation and the Bank in previous times would have been expected to raise interest rates when unemployment fell to such low levels.

Mr Saunders said that he expected the “equilibrium jobless rate” – the unemployment rate associated with stable inflation – for the UK has now fallen below 5 per cent.

And in an indication that he is in no hurry to vote for the Bank to raise rates from their current level of 0.25 per cent, he said: “The economy might be able to run with lower unemployment than previously, consistent with the inflation target.”

The Bank cut rates in August in expectation of a possible recession in the wake of the Brexit vote, but now says that the next move in rates could be in either direction.

Mr Saunders said he was sceptical of the central forecast of the Bank's most recent Inflation report, which projected the jobless rate rising to 5.4 per cent in 2017 due to an economic slowdown brought on by higher inflation and lower business investment.

“Rather than the rise in unemployment forecast in the November Inflation Report, it seems quite possible to me that the jobless rate will stay below 5 per cent this year,” he said.

The Bank will produce its next set of forecasts in February.

Its Governor, Mark Carney, this week suggested that growth forecasts could be revised up in the light of recent stronger survey data than expected.

Other work this week drew attention to the pain in a significant part of the labour market, despite strong headline figures.

Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies today showed that the proportion of low-paid men working part time, rather than full time, has shot up from 10 per cent to 25 per cent since the middle of the 1990s.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies