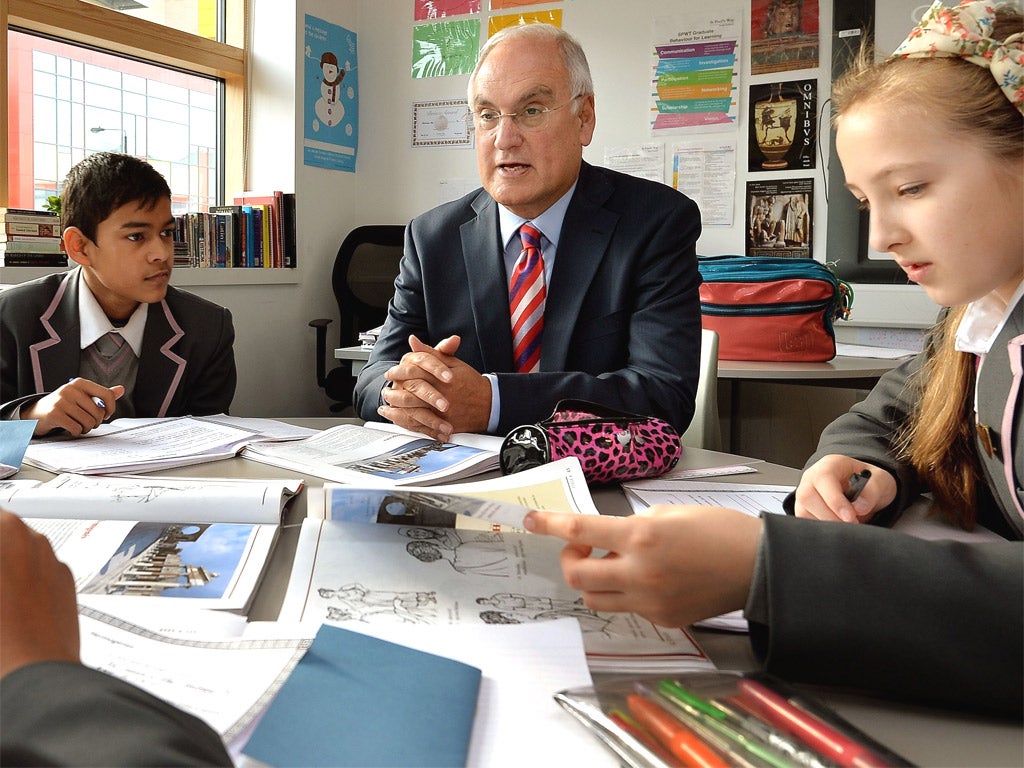

All seven and 14-year-olds must take exams, says Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw

Sir Michael calls for tests abolished almost a decade ago to be reinstated amid concerns over standards in maths and English

A return to compulsory national curriculum tests for all seven and 14-year-olds was demanded today by chief schools inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw as essential for improving standards in maths and English.

The externally marked tests, taken by 600,000 for seven-year-olds, were abolished almost a decade ago after complaints that it was too early an age to put children through the stress of external testing. Those for 14-year-olds were scrapped four years later in 2008.

However, today’s annual report from education standards watchdog Ofsted revealed that - largely as a consequence - the weakest teaching was now seen in the first three years of primary schooling and that assessment of that age group by teachers was “inconsistent”.

By contrast, the strongest teachers were often deployed teaching 10 and 11-year-olds as they prepared to take their national curriculum tests at 11 - which would help schools do well in league tables.

“This suggests widespread deployment of the better teachers to teach pupils who are preparing for tests and examinations,” says the report - which also found there were fewer good or outstanding lessons delivered to 13 and 14-year-olds.

Sir Michael, who is chief executive of Ofsted, made a direct plea to Education Secretary Michael Gove to bring the tests back - a move that is likely to spark an outcry from teachers’ leaders and even lead to calls for a boycott of them if they are reintroduced.

In a speech to coincide with the publication of the report, he said: “Talk to any good headteacher and they will tell you it was a mistake to abolish those tests. That’s because good teachers use those tests to make sure every child learns well.

“On getting rid of the tests we conceded too much ground to vested interests. Our education system should be run for the benefit of children and no-one else.”

He added: “It is really up to the Government as to whether they’re willing to have that battle (to introduce the tests) but I think it is a battle worth having.”

However, Christine Blower, general secretary of the National Union of Teachers, described his call as “an unhelpful step”.

“We already have formal assessment in the early years and the phonics check at age five,” she said. “This is all too much testing too soon.”

Russell Hobby, general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, added: “Ofsted is wrong to set store by increased testing at key stage one (for seven-year-olds). Tests at this age are not an objective measure of performance.” The answer was to improve teachers’ assessment techniques.

A spokeswoman for the Department for Education said it was consulting on primary school assessment arrangements and would be making an announcement “in due course”. It said it expected teachers to be accurate in their assessments of pupils.

In Sir Michael’s report, it also emerged that teaching standards were weakest in maths and English and in the lower ability sets. “Better teaching was seen, generally, in higher ability sets and in the upper age group,” it said.

Around a third of lessons in the two core subjects was less than good. “Without a strong foundation in English and mathematics, children and young people are not prepared for the next stage in their education,” it added.

The overall theme of the report was that there were grounds for optimism as nearly 80 per cent of schools were now judged to be good or outstanding - the highest proportion since Ofsted was founded 20 years ago. In addition, 90 per cent of those that need to improve were making progress.

Sir Michael said the “battle against mediocrity” was being won but major barriers still prevented England’s education system from competing with the best of the world - too much mediocre teaching and weak leadership, massive regional variations on the quality of education and the significant under-performance of children from low-income families, particularly white children.

A total of 1.75 million children were still taught either in inadequate schools or schools which needed to improve before they could be rated as good.

A regional breakdown showed children in many of the country’s urban areas - Camden, Hammersmith and Fulham, Islington and Tower Hamlets - were now guaranteed the opportunity to go to a good secondary. In the Isle of Wight, though, only 14 per cent of pupils attended a good secondary school. Other low performing authorities were Barnsley (22 per cent) and Stoke (34 per cent).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies