Pioneering programme teaches pupils about the dangers of female genital mutilation

Having initially been met with trepidation, the programme is now going nationwide. Maureen Paton meets the women who started it

Mohammed, aged nine, has cut out a line of paper dolls and pinned them to a colourful poster adorned with the abbreviation FGM and the word "Help". His friend David, also nine, has written the supportive message "You Are Not Alone" inside a big red heart, while across the room their classmates Sara and Sia are making up a rap song from the slogan "My Body, My Rules". After whispering and giggling at the start of the 90-minute workshop, the children are beginning to enjoy getting creative with paper, pens and rhyming patter.

"They're often nervous at first, but we break the ice by telling them it's OK to be embarrassed because this is a sensitive and important subject," says the workshop's founder, Saria Khalifa. "We run it really informally and interactively, encouraging them to ask questions all the way through."

This afternoon's session, at a primary school in Brent, north-west London, is part of a groundbreaking schools programme on female genital mutilation. In a child-centred initiative that is the first of its kind in UK schools, girls and boys as young as nine are being taught about the physical realities of FGM. Since it started last May, a pan-London series of FGM awareness sessions has reached 8,200 schoolchildren so far, including up to 400 nine- to 11-year-olds. And now the scheme – run by FGM charity Forward – is also being rolled out in Manchester and Birmingham with other cities to follow.

Age-appropriate teaching methods are used, with secondary-school pupils aged 11-12 being shown plastic demonstration models of female external genitalia and younger, primary-school students, aged nine to 11, watching a more abstract, less explicit animated film, as well as making posters and devising songs. Both age groups, however, are told all the facts about the cutting of young girls' genitalia to control their sexual feelings and thus preserve their "purity" for future husbands. Quite apart from the illegality (if performed on UK citizens, permanent residents or those who are habitually resident in the UK) and the assault on human rights, the long-term health effects include chronic pain and major problems in giving birth. Some of these school sessions have even resulted in young FGM survivors coming forward to ask for help and advice from the charity's outreach programme, with an average of one "disclosure" for every five classes.

The results have been so impressive that a government grant of £176,300 has now been awarded to the charity for a year's work in schools, announced by the education secretary, Nicky Morgan, last month.

This pioneering programme has been created and run by two young London women, after the launch of a pilot scheme four years ago with one of the charity's youth groups in Bristol. Biology graduate Vanessa Diakides, 28, heads up the sessions – devised by her team leader, former medical student Saria, 27 – and goes into schools at the invitation of head teachers. Emotive words such as "barbaric" and "horrific" are avoided; instead they concentrate on the facts – the medical harm caused and the illegality. "We are trying to build up trust and not make students feel that we are out to insult their family culture, otherwise the exact people we're trying to reach would shut down," Vanessa explains.

Yet despite the non-sensational approach, at first there was considerable official opposition. "Even just a few years ago, it was really difficult to get schools – and particularly local authorities – on board," Saria admits. "It was considered too sensitive, that we would traumatise young people, that they wouldn't be able to handle it, whereas we have found that they tend to be really engaged and articulate in their views."

What began to change the squeamish minds of local councils, she explains, was the lead taken by the Metropolitan Police, which has its own dedicated FGM response unit: Project Azure. "The Met was pushing for an FGM schools programme in the south London borough of Greenwich and commissioned us to start it back in 2011," says Saria. "At first it was very ad hoc until we formalised the programme last year."

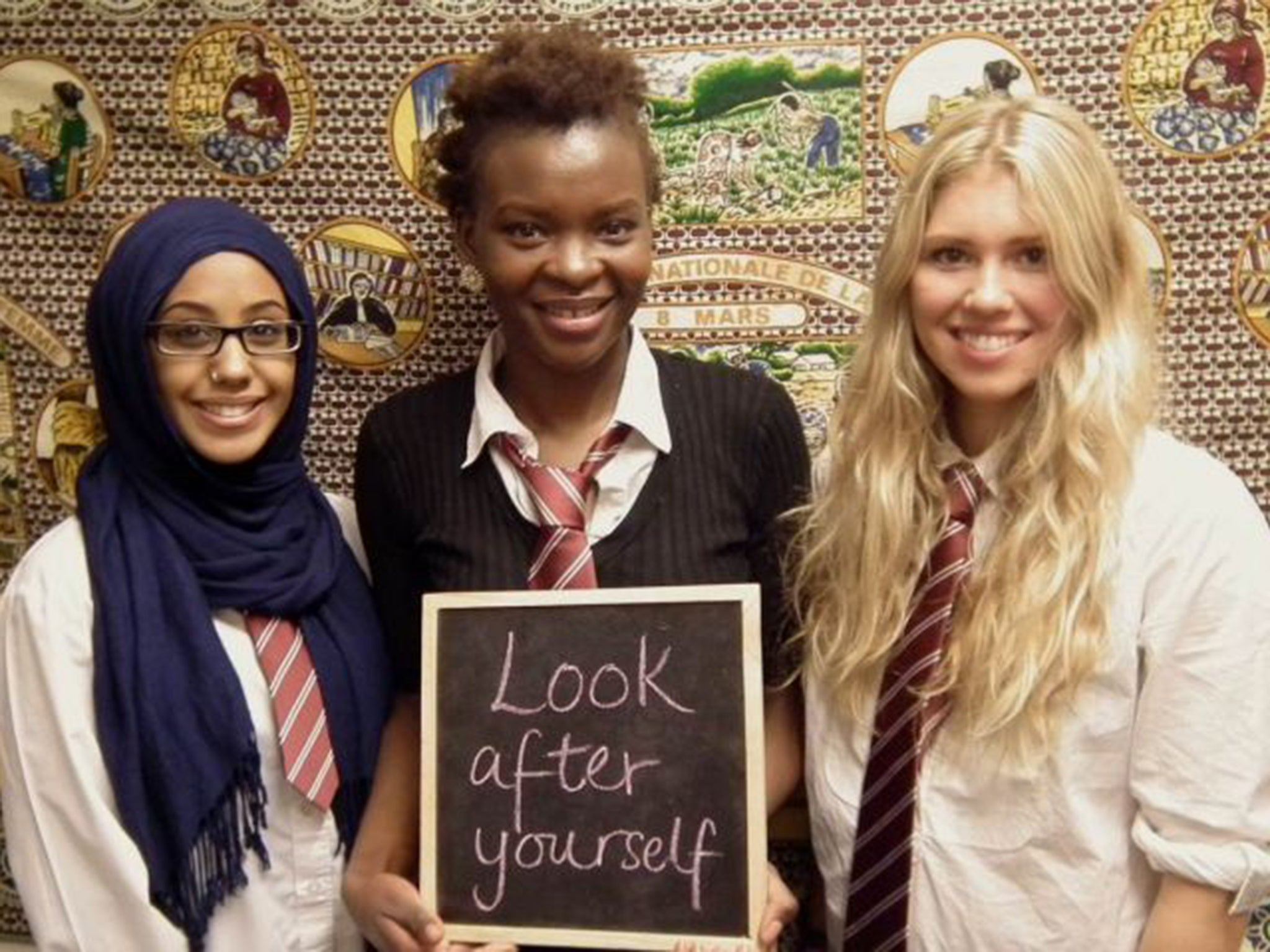

Although the workshop sessions (which are free) tend to be booked by schools in areas from the communities most affected by FGM – Africa and parts of the Middle East and Asia – the sessions don't discriminate, and are delivered to students from all ethnic backgrounds. "It's one of our strictest rules, that we don't create stigmatisation," says Saria, who was born in Britain to a family from Sudan, where FGM is carried out on 88 per cent of girls. "The sessions can be either optional or compulsory, depending on what the head teacher wants."

"How you get schools on board is to make it clear that it's a safeguarding issue," Vanessa explains. "If heads want gender-segregated seminars, we do separate sessions for the boys as well as the girls, because everyone has a role to play in preventing it. It may be happening to the boys' sisters, to their future daughters maybe, to their friends and classmates. We encourage them to talk about it on social media, to tweet and rap about it; it's all about getting them inspired."

I meet Vanessa and Saria at the north-west London offices of Forward (the Foundation for Women's Health Research and Development). It was originally set up in 1983 to end FGM and child marriage in the UK and Africa, by former London midwife Efua Dorkenoo, OBE , who died of cancer in October 2014 after nearly 30 years of campaigning.

Vanessa decided to specialise in work with vulnerable women and girls after witnessing, as a teenager, the very British culture of secrecy around sexual crimes. "A lot of horrific things had happened about 10-12 years ago to friends of mine at school and also at uni," she explains. "People I knew were being sexually assaulted, quite seriously, and then having to carry on as if nothing had happened because no one would talk about it; I found that weird."

Vanessa's background – her English mother is a retired teacher and her Greek-born father is a local councillor in Tottenham – can, she says, often work in her favour by giving her a useful neutrality in such a taboo area; and in the secondary-school sessions, she also provides balance by bringing up Britain's own history of clitorectomies performed by doctors in the 19th century to "cure" hysteria and lesbianism. Students, she says, can be less trouble than the staff: "Some of them giggle when I mention the word 'clitoris'; others get nervous and alarmed and one male teacher ran out to be sick in the corridor."

Parents can pull their children out of the sessions, yet the only time that has happened so far, she says, was when "members of the traveller community in Slough were very displeased about us mentioning female genitals in front of their children. Some heads will describe the sessions to parents as a health and safeguarding issue, others will slot them into a biology lesson and be explicit about the content."

Forward works with parents as well as teachers to encourage involvement; and it has high hopes for Green Party MP Caroline Lucas's Private Member's Bill, soon to receive its second reading in the Commons, to make sex and relationship education – including FGM – statutory in schools. At the moment, it's down to the discretion of individual head teachers about how much, or how little, is taught in their schools.

Despite FGM having been illegal in Britain since 1985, there has yet to be a successful prosecution of this most hidden of sexual crimes, estimated to have been performed on 137,000 girls and women in the UK with a further 60,000 girls under 15 at risk (and more than 130 million victims worldwide). With many adults unwilling to admit the problem, this child-centred approach creates a safe space that will enable the survivors to come forward afterwards – if they wish. "We have a safeguarding responsibility ourselves so we do have to report disclosures and refer them for help and counselling, but we make that clear to the girls so that they don't feel a confidence has been betrayed. We are not there to shock or campaign; we are there to inform and educate," Vanessa concludes. "It's really important not to victimise people in your head, thinking, 'Oh you poor dear, let me cry for you.' It's much more about empowerment – and how we can support them."

All children's names have been changed. Go to forwarduk.org.uk or ring 020 8960 4000 for more information

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies