3,000 miles, 10 months: one Australian’s march for indigenous rights

This 27-year-old is walking across his homeland to highlight the continued mistreatment of its First Peoples, whose calls for special representation in parliament remain ignored

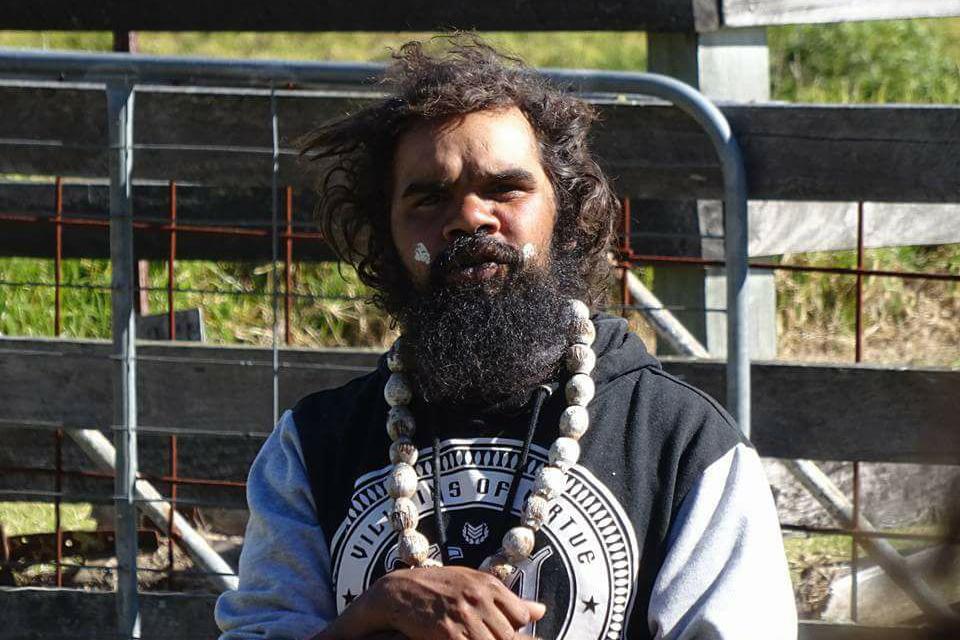

Clinton Pryor’s already walked nearly 3,000 miles by the time I meet up with him on a Thursday morning. We’re on a country road between Sydney and Melbourne.

Pryor, an Aboriginal activist from Australia’s west coast, is starting his 310th day on foot to protest against the treatment of indigenous Australians, and he seems anxious to get going.

He takes a final drag off a cigarette. “Ready, guys?” he says, looking toward his support crew – grandpas with long white beards, one driving a white station wagon barefoot, the other astride a bike.

His girlfriend, Kerry-Lee Coulthard, who met Pryor when he passed through her hometown in central Australia, eyes the road ahead. And with that, Pryor’s Walk for Justice continues.

9:42am – Developing a voice

“We’re doing this for the grassroots people,” says Pryor, a mile into the walk. “A lot of people are not being heard.”

The 27-year-old, who wears a knee brace on one leg, says he started out his trek from Perth to Canberra to raise awareness about two specific issues: homelessness among indigenous Australians, an issue he has experienced firsthand, and the forced closing of remote Aboriginal communities by the government, which he has been protesting since at least 2014.

Over time, though, he said his mission has evolved to reflect what First Peoples have told him they were struggling with. Suicide. Poverty. Racist policing. Corruption. Lack of rights to land, lack of work, and perhaps most of all, Pryor says, lack of inclusion in decisions made by the government.

“This is a civil rights movement,” he says. “The power should be shared.”

He talks about the importance of a treaty, which he says should have been signed 229 years ago, when the first European settlers landed in Australia. He emphasises that services for Aboriginal communities, including access to water and education, need to be expanded. And at times, he seems frustrated with the whole idea of politics, declaring, “We just want things done right.”

Sovereignty comes up often, as it does in other contexts. In May, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island leaders agreed on a set of demands – the “Uluru Statement from the Heart” – which called for First Australians to be given greater control over their lives by creating a permanent representative body enshrined in the constitution.

At the Garma Festival earlier this month, a meeting of indigenous leaders and chiefs of political, business and industry groups, the call for representation was repeated. But Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, who was there, resisted those demands.

“An all-or-nothing approach often results in nothing,” said Turnbull.

Neither Pryor nor others seemed to have broken through with their message. The Walk for Justice has been covered sporadically by the local news media, and Pryor’s following on Facebook and Twitter is yet to force Canberra to pay attention.

“Our parliamentarians struggle to respond to anything that comes from the Aboriginal community,” says Megan Davis, a Cobble Cobble woman from Queensland and a law professor at the University of New South Wales who is a member of the Referendum Council that advises lawmakers on how to advance recognition for indigenous Australians.

“It’s shocking that in 2017 you still have to be arguing that point – that we should actually be at the table when you’re discussing our issues.”

12:18pm – A team emerges

Pryor relies on other forms of encouragement. Just after noon, a man parks his truck across the road, runs to Pryor and hands him a few 20-dollar bills. “Doing good, brother. You’re making us all proud,” he says before dashing away.

When it starts to rain a few minutes later, Noonie Raymond, a member of Pryor’s support team, delivers large umbrellas, one for him, one for Coulthard.

Raymond is on a mountain bike. Brett Burnell drives the station wagon, a 1999 Ford Falcon packed with supplies and signed by dozens of well-wishers during the journey.

With their matching shirts and long, grey beards, Raymond and Burnell look like brothers; they are hard to tell apart.

Both men, longtime activists without Aboriginal roots said they joined Pryor to help right the wrongs of their country’s past.

“We’re learning our history, which we weren’t taught growing up,” says Raymond .

The challenges have varied. The Ford Falcon, bought for 1,300 Australian dollars (£800), was a replacement for a Mercedes van that Burnell started out with, but crashed after drifting asleep at the wheel. In the desert, Pryor says, they went two days without water, and at one point, Pryor’s left leg swelled with fluid, forcing him to walk 31 miles in excruciating pain.

As a group – with around a half-dozen team members on the road and helping with social media and organisation – they’ve been pushing ahead through donations.

Pryor has raised a little more than £20,000 through a GoFundMe page, and gifts of food, money, car parts and the occasional place to stay have also helped.

One especially fortunate gift of lodging led to Pryor meeting Coulthard.

Six months ago, he was staying in Port Augusta, a small city north of Adelaide, when he noticed a woman hanging laundry next door. It was Coulthard.

“He must have been stalking me for 10 minutes,” she says, shyness giving way to humour. “He came up to me. Then we spent three hours talking.”

Asked what they talked about, she chuckled. “He asked about my dreams,” she said.

She told him how she’d always hoped to help the homeless. She told him she’d always hoped to visit Hawaii.

Before long, Coulthard, 30, was travelling to see Pryor between long stretches of walking. She overcame her fear of flying. And he changed, too.

“I stopped drinking,” he said. “All because of her.”

2:20 pm – A shared mission

Pryor’s feet sometimes fall behind schedule.

Admitting he was a bit slowed down by Coulthard, who doesn’t usually join him, he jumps in a car just before 2pm to drive to a march in Nowra. (His team marks where he’s stopped so he can return and start again later.)

At a riverside park, dozens of people gather. Sausages cooked on a grill. A police officer with white face paint on his cheeks waves cars in as Paul Mcleod, 60, an elder whose mother was part of the Yuin nation, lights a ceremonial fire and performs a traditional dance.

“All of our people walk with him, in the spirit, if not in the flesh,” Mcleod tells the crowd in English and in local languages. “It means a lot. To all of us.”

Pryor, his face also painted, also speaks. He identifies himself as a Wajuk, Balardung, Kija and a Yulparitja man from the West, and most of what he argued for sounded similar to what he’d told me on the walk.

But he also seems to struggle with how to explain his purpose. At one point, he apologises for losing his train of thought. He says he was tired from walking.

He looks 10 years younger, surrounded by men, women and children still seeking equality hundreds of years after colonisation, on behalf of ancient peoples who have inhabited Australia for at least 65,000 years. Earlier in the day, he had asked me how to spell a few common words – such as ‘Europe’ – and admitted that he’s struggled with illiteracy.

By the end of his speech, though, he finds his footing. In 2004, Michael Long trekked from Melbourne to Canberra, to put Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples back on the national agenda. More than a decade later, with hundreds of miles to go, Pryor casts his own walk as an act of resilience.

“I’ve been walking for 10 months,” he said. “It’s about telling everyone to get back up and keep fighting.”

© New York Times

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies