The Summer of Love: fact or fiction?

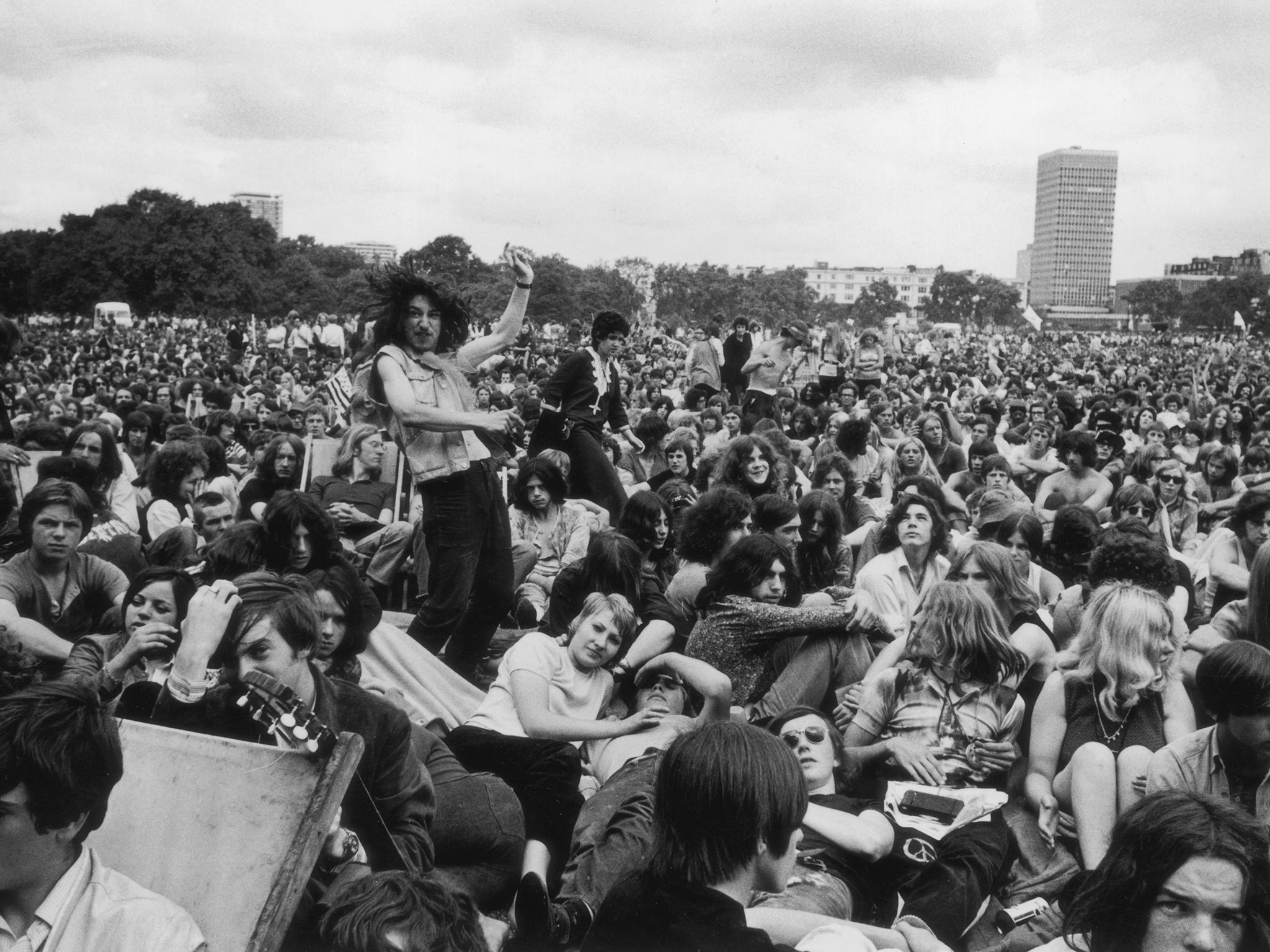

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love. But, asks David Lister, how much of it really happened – and how much of it is mythologising and self-mythologising, both at the time and in the decades that followed, a yearning for a past that never was?

Love will for the next few months be not just in the air, not just all around, but full-frontally assaulting us. For this year sees the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Summer of Love. We live more than ever in an age obsessed with anniversaries, and you can be sure that none will arrive with as much homage, as much music, as many psychedelic colours as this one. Even before the turn of this year, Shakespeare’s Globe theatre in London was out of the blocks. Announcing its 2017 season of Shakespeare plays it proclaimed, predictably, the “Summer of Love season” with the even more predictable instruction to audiences: “Be sure to wear flowers in your hair. ”

Others are certain to follow, perhaps quoting the line from the 1967 song a little more accurately, perhaps not. Few will notice. Precise quotation, like the summer of 1967 itself, is lost in a drug-infused mist. Precision, memory and hard reality were never among the foremost hippy virtues. So, as we celebrate that time of free love, good will to all men and lashings of good will from men to women, we should pause to wonder how much of it actually existed.

For some, of course, it did. There were be-ins, love-ins, The Beatles releasing Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, (now being memorialised in expensive box sets and of outtakes), Pink Floyd and other trippy bands playing all night festivals, long hair a requisite, as if it ever signalled anything more profound than a need to conform. But I maintain it was a small minority who indulged in these multicoloured fantasies.

As the cultural historian Andrew Roberts wrote in The Independent on an earlier anniversary of the Summer of Love, “In this England, respectable fathers would favour car-coats, listening to Mrs Dale’s Diary and driving Morris Oxfords with starting-handle brackets and leather upholstery rather than sporting a kaftan at the wheel of a psychedelic Mini … In 1967, the BBC was still screening The Black & White Minstrel Show. Homosexual acts were partly decriminalised. Forty years ago, Britain was fighting a bloody colonial battle in Aden, unmarried women might still be refused the Pill, and ‘orphans’ would still depart from Tilbury to a new life in Australia.”

And, on a less exalted level, it has also been conveniently forgotten that in that year when music was the voice of youth displaying their revolutionary and psychedelic credentials, the best double-A side (remember those? ) ever released, “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields Forever” by The Beatles, was kept off the number one spot by Engelbert Humperdinck’s “Please Release Me”. Perhaps there should be an anniversary to commemorate the triumphs of the middle of the road against all adversity. Yet still we refuse to accept that the Summer of Love was anything but a golden age, when hippies (slowly) roamed the land spreading peace and harmony, you took the train to work, with a joint in your hand and flowers in your hair, love and sex were freely available, with no impediment caused by lack of previous acquaintance or acne.

If you remember the Sixties you weren’t there, said John Lennon supposedly. Though if you remember precisely who said that memorable and much claimed quote, you probably also weren’t there. If you remember the Summer of Love you were there, but almost certainly wishing you were playing a greater part in it. And, how the memory can play tricks. Mike Bartlett’s recent, acclaimed play Love, Love, Love was partly set in that momentous year, and had a character so distracted by love that he punched the air and exclaimed “Yes!”

1967: The truth about the summer of love

Show all 2Well actually, no. In 1967 no one punched the air exclaiming “Yes!”. That gesture came decades later. It’s a tiny but typical example of how we not just misremember the Summer of Love, we see it through the prism of today, largely to wallow in the contrast between a present of anxiety, distrust and fear and a past remembered as harmony and tender, positive emotion. Contrast there was at the time, too, neatly expressed in the introduction to the book Summer of Love by the late Beatles producer, George Martin. What a cunning title that book had. A book about the making of the Sgt Pepper album cashing in on a phrase that even at the time of publication, 1994, was developing mythical qualities. Martin wrote: “It was the Summer of Love. US Air Force B-52s were dropping 800 tons of bombs a day on North Vietnam; Mao Zedong’s Red Guards had the whole of China by the throat; and Biafra’s Ibo people were starving when they were not being massacred. “But from where I was sitting, at EMI’s Abbey Road studios in west London, people in their thousands were giving themselves over to Peace and Love.

They were dropping out, growing their hair, painting their bodies, and inventing sex. They contemplated revolution, and their navels. Flowers gave them power. They had pot and acid, optimism and enthusiasm. They had ‘happenings’, ‘be-ins’ and ‘love-ins’. They had idealism, energy, money and youth. And they had one other thing. They had music. ”

I agree. There were – just – thousands doing these exotic things and deluding themselves that flowers gave them power. They did have money. And they were, for the most part, in London. Somehow, an indulgence by a tiny and affluent part of the nation’s demographic, in largely one area of the country, has come to be seen as a universal phenomenon which sprinkled its fairy dust on the young everywhere, from Newcastle to Rochdale, Wolverhampton to Truro, not just the King’s Road to Carnaby Street. If anywhere can claim to be the birthplace of the Summer of Love, it is San Francisco and in particular one district, Haight-Ashbury, where tens of thousands gathered at one point, and where many more young Americans in colourful clothes made a pilgrimage during the year. But as Joel Selvin, senior pop critic with the San Francisco Chronicle, has written: “The mythology of that summer in 1967 has never disappeared.

The San Francisco hippy, dancing in Golden Gate Park with long hair flowing, has become as much of an enduring American archetype as the gunfighters and cowboys who roamed the Wild West. More importantly, the rise of Sixties counterculture has had a significant impact on our culture today. The Summer of Love resonates in strip mall yoga classes, pop music, visual art, fashion, attitudes toward drugs, the personal computer revolution, and the current mad dash toward the greening of America. While some of the counterculture's dreams came true, others, particularly the movement's idealistic politics, evaporated like the sweet-smelling pot smoke that saturated the air that summer.”

Even that may be crediting a little too much to the “idealistic politics” of that summer (and certainly to the origins of the personal computer). To the background of the Vietnam War, which cast such a huge shadow over that decade, it was understandable that a young generation, many of whom were likely to be drafted, would seek a politics of reconciliation. But hippy politics were actually no politics at all. A philosophy of peace and love and little more could not begin to offer a solution to the world’s conflicts or offer an alternative political approach to that being pursued by Western democratic governments. Nowhere can one find any sort of cogent political philosophy from the young of that era.

In Britain the nearest thing to it came from the underground press, but its anarchical agenda also offered little apart from the freeing up of sexual repression and challenges to censorship. The feminist revolution of the late Sixties and early Seventies also began to cast the Summer of Love in a less favourable light. Free love seemed a glamorous and delightfully parent-shocking concept at the time, but it came of an age when all the leaders were male, and it offered males the opportunities afforded by a boundless supply of nubile young women (as far as could be seen from George Martin’s studio window at least). For the young women involved, in an age group ostensibly subscribing to a philosophy of free love, and a society in which male wishes were paramount, the benefits were less obvious.

Mythology surrounding the summer of 1967 is the same as the mythology surrounding the Sixties as a whole. It was far from a time defined by revolution, anarchy, hippiedom, and unfettered love with endless supplies of drugs to a trippy soundtrack. All these things existed, but in corners, publicised and exaggerated into perpetuity.

A portrait of a young nation doing its homework, being respectful to its parents and perhaps wishing for but actually finding little adventure at a time when gap years hadn’t been invented, is a less glamorous tale, and one that social history has largely chosen to ignore. It is a portrait of the Sixties that does not fit the narrative. As individuals we try to paint a better picture of our own past by adjusting our memory of events until we are convinced that what we remember must be true. Individuals do this. But rarely if ever can this massive, dishonest and self-glamorising adjustment of memory have affected an entire nation, perhaps an entire world, as it has over the Summer of Love.

As if on the drugs that we like to remember there being, we have bought into a collective rainbow-flecked memory of a summer drenched in love. As our parents and grandparents have decided to remember the summers of their youth as forever sunny, so we Baby Boomers have decided to remember this particular summer as forever and unrepeatably passionate. The myth of the Summer of Love is a cultural comfort blanket, enveloping us in the warmth of shared memory. The accuracy of that memory is immaterial. Our collective psyche demands that we were all once daring, dangerous, adventurous, experimental, revolutionary, romantic and free, existing on a diet of love in a never-ending summer. The alternative is too grim to contemplate.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies