Andy Rooney: Writer who found fame with his grumbles about modern life on CBS

Every American age has had its licenced curmudgeon. A century ago Mark Twain filled that role, then came Will Rogers and HL Mencken. The latest of that line was Andy Rooney, whose pungent television commentaries about life's myriad petty irritations made him a national institution.

Rooney's soapbox was CBS's venerable 60 Minutes weekly news magazine, broadcast every Sunday evening. For more than 30 years, from 1978 until just a month before his death, he held forth for a couple of minutes at the end of the show, more often than not grumbling about something.

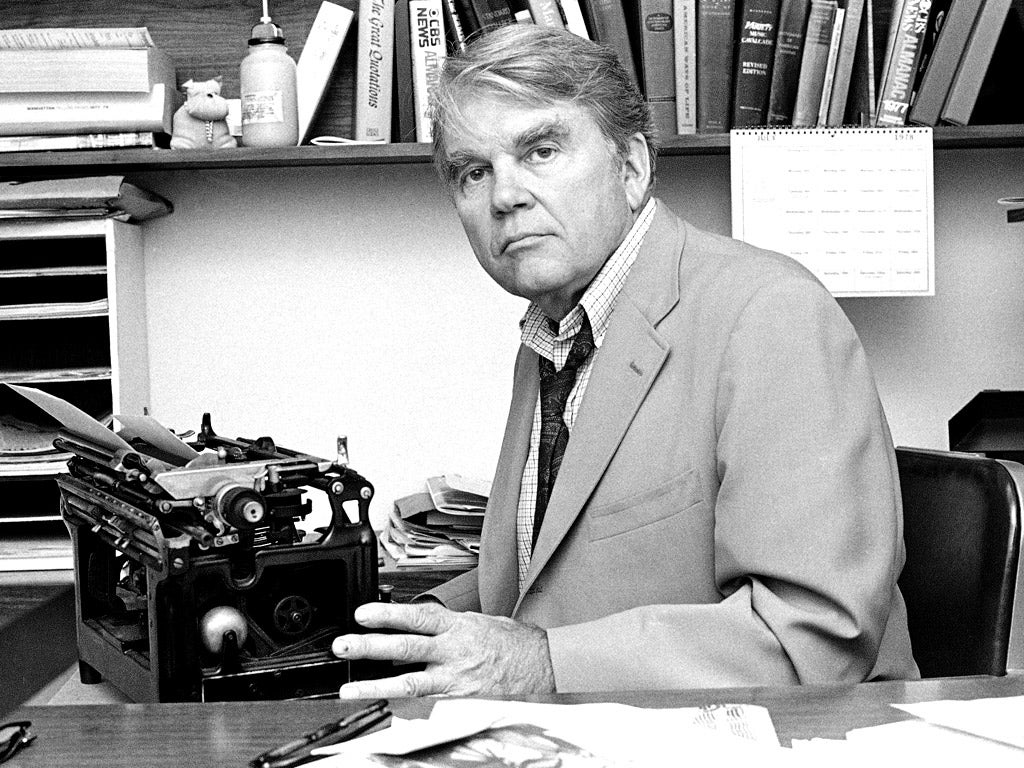

The segment was filmed not on a studio set, but with Rooney sitting behind his desk in his cluttered office. His target might be anything: the spuriousness of much modern art or the pointless cotton wads you find in pill bottles, the ordeal of New Year's Eve or the problems of turning a computer on and off. If Bill Gates had invented television, he once mused, "You'd need two hours to watch 60 Minutes."

Occasionally he would tackle a serious subject – in 2003 he criticised the Iraq War, and earlier this year spoke of his rejoicing that Osama bin Laden had finally been killed. But mostly he sounded off on his pet peeves. In one 1994 show he offered his list of the five worst inventions: electric hand driers in public washrooms, "useless" dust jackets on books, pop-top cans, venetian blinds and the ballpoint pen. In Rooney's experience these latter invariably didn't work; fountain pens, he told viewers, were far more reliable.

Viewers loved it, but anyone who complains in public for a living is bound sooner or later to sound off about the wrong thing, and Rooney did so more than once. His costliest gaffe came in 1989, when he listed "homosexual unions" among "self-induced ills which kill us," and followed that up by giving an interview with a gay newspaper in which he reportedly disparaged the intelligence of African Americans.

Rooney denied the latter slur (the interview was not recorded), but accepted a three-month suspension by CBS. In the event, he was back in his slot on 60 Minutes within a month. Shorn of Rooney's commentaries, the programme had lost 20 per cent of its ratings at a stroke.

Although it was his quirky television appearances, with his persona of cantankerous old-timer, that made him nationally famous, Rooney always regarded himself first and foremost as a writer. That had been his goal, he once said, ever since a high school English teacher had told him he had a talent for the written word.

Drafted into the army in August 1941, he talked his way into a job as a reporter with the US military newspaper Stars and Stripes. He flew on bombing missions over Germany, covered the bloody 1944 D-Day landings on Omaha Beach and was one of the first Americans to enter the Nazi concentration camps.

After the war, Rooney joined CBS as a writer for radio and television, striking up a close friendship with Walter Cronkite, who would become America's most famous news anchor, and other leading lights of the network including the reporter Harry Reasoner, who delivered a series of "Everyman" essays, scripted by Rooney. "Someone had to write what they said, and that was me," he put it in typical down-to-earth fashion.

In his final years on 60 Minutes, the advancing years took some of the edge of his performances, but the public still loved him. In his 1,097th and final broadcast on 2 October, Rooney gave thanks: "I've done a lot of complaining here, but of all the things I've complained about, I can't complain about my life." His only regret, he once confessed, was that "insignificance didn't have more stature." In his hands, it did.

Rupert Cornwell

Andrew Aitken Rooney, writer and commentator: born Albany, New York 14 January 1919; married 1942 Marguerite Howard (three daughters, one son); died New York City 4 November 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies