Egon Ronay was a genius at self-publicity. The Hungarian-born restaurateur, journalist and guide-book compiler, and self-appointed campaigner against bad public catering in motorway eating-places, had the gift of getting his name in the newspapers.

He managed to do this despite enclosing himself in a carapace of mystery, refusing ever to give his date of birth – in his Who's Who entry, or even to those who tried (in vain) to get a CBE for him, and were required to fill out an Honours Nomination Form. He had his reasons.

Ronay was born in Budapest, says his entry in Wikipedia (the sole source of a date of birth) on 24 July 1915. He was educated, he says in The Unforgettable Dishes of my Life, a 1989 memoir-cum-recipe book, as a day-boy at a school belonging "to the Catholic teaching order of the Piarists, much like the Benedictines and widespread in Central Europe." Having "confessed" to playing the piano, he was appointed the school organist "for four long years," which "put me off church for some time." The "fathers drove us hard academically," and he was grateful for the ten-minute intervals between lessons that allowed him to buy an Imperial bread-roll and some milk from the school caretaker whose perk was the baked goods concession.

Ronay's grandfather "built a 120-room hotel in Pöstyén, Northern Hungary, in 1910" he says, and the profession "was continued by my father, who owned and ran five of the best restaurants in Budapest between the two wars." These included the fashionable Hangli, one of Budapest's celebrated garden restaurants. His father, he never tired of telling interviewers, was "Budapest's fifth-highest taxpayer"; the family was seriously wealthy – and he was an only child.

He told the Evening Standard in 2005 that "I spent every summer in England from the age of about eight, because my father was very keen I should learn the language. I fell in love with the country. Later, when I was studying law at Budapest, I went to summer schools at Cambridge University." He shared the Anglophilia common among his countrymen – and though he spoke the accented English common to most of the Hungarian emigrés of his era, he wrote very serviceable, fluent English prose.

He gave up the law to go into the family business – though having taken his LLD from Budapest University, he remained forever litigious; and many journalists (myself included) will have memories of publishing what they thought were neutral or even favourable references to Ronay, only to be followed by a letter threatening a writ. Before going into management he went into the family's kitchens, then continued his training abroad, finishing up at the Dorchester.

He doesn't say whether his mother, Irene, had Transylvanian antecedents, but when his father opened a restaurant in the 1930s specialising in this rustic cuisine, she trained the head Chef Papp, using her own experience and recipes she had researched in old books. She was obviously a very good cook, though this fact is at slight variance with what he had to say about his family's social position: cooking was seldom one of the accomplishments of well-born ladies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In his memoir Ronay commented explicitly on the family's social status in this anecdote: "Someone had made a stupid but offensive remark about the social standing and family background of my closest friend and me (we were both 20). The code of our circle was merciless: there had to be a duel."

The story is funny, its telling ironic and laced with self-mockery, as his friend was chosen by lot actually to fight the duel, and the wonky pistols missed their targets; but the implication of membership in the upper classes is not lost upon the reader. He also writes of the balls "for 400 or 500" he went to, and paints a picture – heavily embellished by cream and pastries – of la douceur de la vie between the wars.

At the same age (20) he married his first wife, Edit, the mother of his extraordinarily talented daughters, Esther (the elder, born 1943 or earlier, a film editor and director) and Edina (born 1945, an actress in Carry On Cowboy and some episodes of The Avengers, as well as a fashion designer, and mother of the actress Sheba Ronay), both of whom were born in Hungary. This first wife was airbrushed out of Who's Who, merely crediting the daughters as "by a previous marriage," though he told the Standard that Edit joined him in London with the one-year-old Edina.

The secret Ronay could not tell his supporters or his organised fan club (of which more later), the reason he was never awarded an official honour, and presumably his motive for withholding his date of birth from the published record (neither "Egon" nor "Ronay" is an uncommon name in Hungary, and it would have been difficult to find his war record without knowing that date), was that he had been an enemy combatant in the Second World War. Hungary was the first country to adhere to the Tripartite Pact of Germany, Italy and Japan. Britain declared war on Hungary on 6 December 1941 and Hungary declared war on Britain a few days later. Ronay says he was was conscripted, and was part of the occupying forces after the Vienna Awards, when Hitler and Mussolini gave Hungary Southern Slovakia and Northern Transylvania.

He claimed to have deserted in 1943, and told the Standard, "There was so much confusion it was possible but risky, so I went into hiding." He also said he took no part (at least in uniform) in the Siege of Budapest, one of the bloodiest battles of the war, from 29 Dec. 1944- 13 Feb. 1945, when Soviet forces finally defeated the Wehrmacht and the SS for control of the city. The Ronays suffered in 1944, when the Soviets in the east began shelling the Western part of the city where they lived, and they took refuge in the cellar.

"All the magnificent bridges ... except one, over the Danube, were destroyed, and two of my father's restaurants," he told the Standard. The winter was especially cold, so though "there were bodies everywhere ... they were frozen. Also, there were dead horses lying in the street, and some people managed to cut meat from them to eat." One of his father's restaurants was lost to Russian reprisals – they drove a tank through the dining room and kitchen – and also pillaged by retreating Germans, who left only big sacks of ersatz coffee, with which Ronay attempted to reopen the place as a café in late 1945.

The next week he says he was rounded up, with a dozen others, by a patrol, and threatened with being sent to Siberia as part of a work gang. One of the guards, however, was a soldier he'd served two days earlier in the café, who recognised him. "So I said to the interrogator, I am not a fascist, I am a waiter, a worker, and this man knows me." He was the only one released – "Fortunately, they did not look at my hands." His parents were "exiled by Stalinists to a peasant village," and, as he'd fought on the wrong side, it was evident that he must leave; he said the mayor of Budapest got him an exit visa. By his own account he must have been in hiding for three years.

Penniless, and leaving behind his wife and two children, Ronay left for London on 10 October 1946 – he didn't return for 37 years, saw his mother only once more, and didn't attend his father's funeral in 1959: "I would have been arrested immediately." It would be interesting to know how Ronay convinced a British immigration official to admit even an involuntary enemy combatant in 1946, as most of the emigrating Hungarians since the beginning of the War had been Jewish. He appears to have been naturalised as a British subject soon after – at least this assertion was made on the application for honours. Either the authorities did not know of his war record, or he was accorded British nationality despite having fought for the enemy, perhaps because British officials had reason to believe his story – though that would make it odd that he was later refused an honour.

He got a job almost immediately, as manager of the Society Restaurant, Jermyn Street, and subsequently of 96 Piccadilly, "elevated to fame by a visit by the then Princess Elizabeth... a large establishment of many elegant dining rooms." It was his job to "dress the room," to seat people so that on entering customers could spot the celebrities of the day, or would at least see tables filled with pretty girls. In 1952 someone loaned him £4,000 and he opened his own 39-seat restaurant, the Marquee, in Knightsbridge, opposite the side entrance of Harrods.

As chef he brought Jean Bardes from a well-known old-fashioned eatery in Beaulieu on the French Riviera, who served what Ronay claimed were an authentic pâté de campagne, "matelote d'anguille smacking of Bordeaux, classic bouillabaisse exuding Marseilles, to name a few," though the last is famously impossible to reconstruct with the fish available in Britain. Fanny Cradock, then the Daily Telegraph's food writer, spotted a soul-mate.

A liar (she was a double bigamist when she finally married Johnny), self-invented food expert who knew even less about food than Ronay, and had hard-core suburban taste, she called the Marquee "London's most food-perfect small restaurant," got Ronay to join her "Brains Trust" flying circus, where Fanny and Johnny toured the country giving cookery demonstrations, preceded by what the three of them regarded as "highbrow discussions" about food and wine. When Cradock defected to the Daily Mail in 1954 Ronay took over the Daily then Sunday Telegraph slot for six years. He continued to own the Marquee until 1955 – the ethical standards of journalism being different in those days.

During this time he put together his first Egon Ronay Guide, which appeared in 1957. It was a success. Though his own knowledge of food was limited to Central Europe and a bit of France, his palate, said Andrew Eliel, who worked with him on the Guides much later in the 1990s, "was impeccable." From the beginning Ronay had a knack for finding good people to work for him, and in the 1960s and 70s employed substantial figures such as the chef Simon Hopkinson and the late Alan Crompton-Batt. Ironically, the first Guide praised the food served at the Airport Restaurant in what is now called Heathrow, but it also puffed The Ivy, Mirabelle and Bentleys (all now enjoying a second wind).

He carried on writing and publishing his restaurant guides, encouraging the reticent British to complain and demand better food and higher standards of service until 1984, when he sold the Guide – and his name (which he won back in a High Court action in 1997) – to the AA, a move he came bitterly to regret. In fact, by the 1980s, his guides were distinctly old hat. They had been superseded at the higher level by the red Michelin Guide to Britain, and at the lower by the users'-democracy of the Good Food Guide.

The Michelin inspectors had more training and more generous expenses than Ronays' (which were always for a meal for one without wine), and the reader-contributors of the Good Food Guide knew about those cuisines – Indian, Chinese, Thai – becoming important, at least in London, of which Ronay then had small personal experience or liking.

Moreover the French had created their nouvelle cuisine, not something very sympathetic to the author of a cookbook giving among his favourite recipes, Reveller's Soup: flour-thickened stock served with tinned sauerkraut, lard, smoked bacon, frankfurters and soured cream.

In 2005 he published his guide to what were supposedly the country's top 200 restaurants, the first title to carry his name since his High Court victory, and the first over which he had had complete editorial control since 1984. Published in association with the RAC, the guide was a moist squib, ranking number 159,745 at year's end in Amazon's book sales, as opposed to the Michelin 2006 published at almost the same time, and ranking 11,278. His name was, of course, unknown to the young bankers-with-bonuses clients of restaurants such as the high-end Sketch, whose over-design and big prices he particularly and virtuously loathed.

He was well-off, with a grand house in London and a pile in Berkshire, overlooking the Downs. In 1967 he married Barbara Greenslade, a pianist of concert standard, and more recently an accomplished painter. (They adopted a son, Gerard, who enjoyed a vogue as a chocolatier, publishing Chocolate Kit in 1997.)

Consulting for the BAA's seven airports from 1992-2002 gave him continued comfortable access to travel, and even his 1989 book makes it clear that by that date he'd travelled to America, North Africa, Italy and extensively in France, where frequent travelling companions were the New York Times' political and food journalist, the late R W "Johnny" Apple and his wife, Betsey. Ronay was musical, and had a genuine love of concerts and opera, and evidences in his 1989 memoir that he was interested in and knowledgeable about architecture.

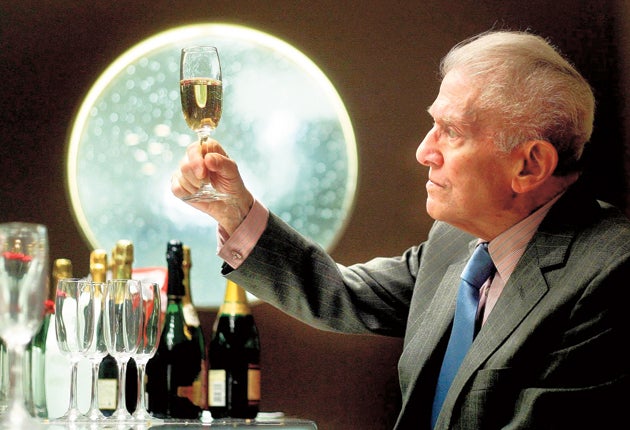

Ronay was a dapper, small man, trim and fit well into his 90s because he continued to do the daily Canadian Air Force Exercises. He was always well turned out, with beautifully tailored clothes. However, he was a vain man. His vanity reached its apogee in 1983 when, in imitation of the French l'Académie de Gastronomes, a slightly bogus body that elected him to membership in 1979, and another gourmandising group, the Club des Cent, he founded the British Academy of Gastronomes and became President for life.

More than one restaurateur has told me how much he dreaded being chosen for the "honour" of dining Ronay's Academy, as the special price negotiated always meant a big loss for the establishment, combined with the nuisance value of having to cook a menu of Ronay's choice, and then having to endure listening from behind the green baize door to Ronay's course-by-course criticism of the non-profit meal. Few of his distinguished associates in his Academy were aware of these details or of the group's unpopularity with London's chefs.

In the late 1990s Ronay and I had had a trivial tiff about something, and, after the ritual waving of the writ, agreed to meet and make it up. We did so at a lunch at the old Tante Claire in Royal Hospital Road. I was not entirely surprised that Egon had been careful to commission a photographer to capture the occasion of our handshake; but when invited to join his Academy I politely made my excuses.

Ronay had succeeded in becoming a brand, and for people who were a certain age in the 1970s, his name was a talisman. In later years Ronay righteously attacked those who abused their monopoly position in catering for the public, such as motorway cafes, airlines and hospitals. As anyone who has recently been forced to have a meal in any of these knows, he did not achieve much beyond gaining a glimmer or two of the limelight for himself.

Ronay's taste ran to gulyás (as it should be spelled), sole Walewska and dinner at Maxims in Paris – all emblems of the early years of the last century or the last years of the one before. Was he a force for gastronomic good? Did he actually improve anything beside his own bank balance? Probably not. But this strange, sometimes impressive Hungarian bundle of contradictions will make a small, but diverting footnote to the history of gourmandise.

Egon Ronay, restaurateur, guidebook compiler, journalist, gastronome, born 24 July 1915, Budapest; married twice; 1935 Edit, (two daughters); 1967 Barbara Greenslade , (one son, adopted); emigrated to UK 1946; died Berkshire, 12 June 2010

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies