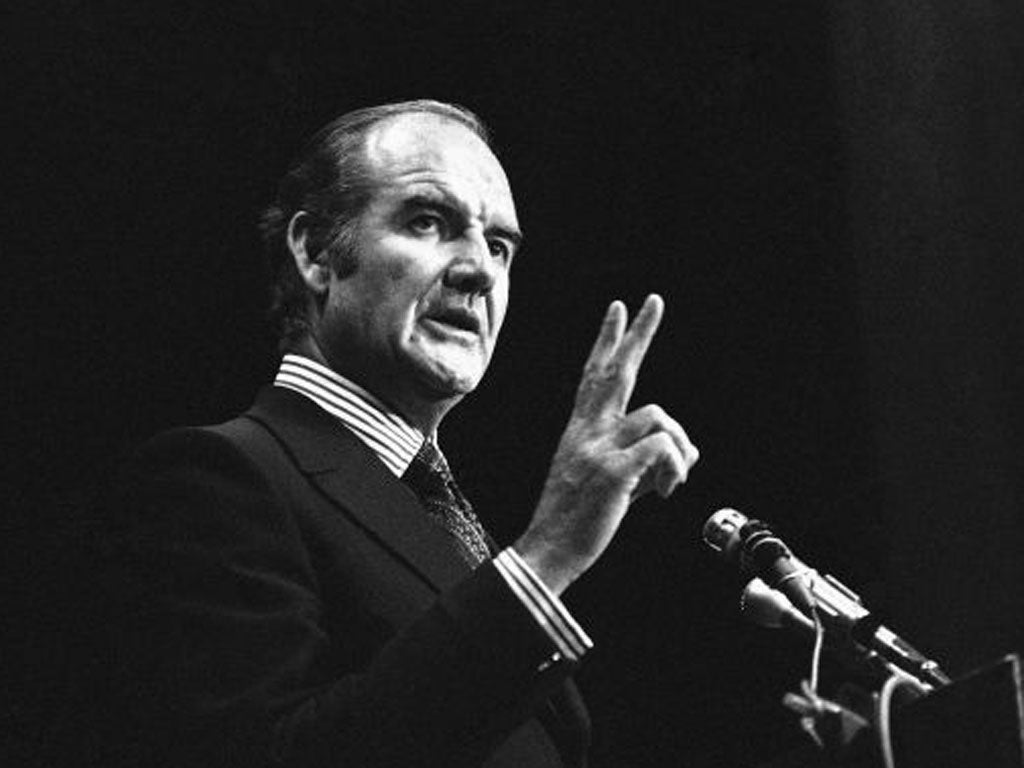

George McGovern: Admired politician whose career was overshadowed by his landslide defeat against Nixon in 1972

George McGovern was a brave Second World War air force pilot. He served three terms as an admired Senator for his native South Dakota. Late in life he became a diplomat and indefatigable advocate for the world's poor. But he will be above all remembered as the man on the wrong end of one of the biggest landslides in presidential history.

His shambolic 1972 campaign became an emblem of all that went wrong with the Democratic Party between the decline of Lyndon Johnson and the election of Bill Clinton a quarter of a century later. As both a social liberal and Vietnam war dove, his views were too much for a substantial section of his own party, not to mention the wider electorate.

Personally, McGovern was the most decent and honourable of men. His misfortune, however, was to run against the most ruthless and cynical president of modern times. Even Bob Dole, a bitter political opponent of McGovern and in 1972 a hit man for Richard Nixon, would later admit, "George McGovern is a gentleman and has always been a gentleman."

The future presidential candidate imbibed his strongly moralistic outlook from his father, a Wesleyan Methodist minister in Avon, South Dakota, a tiny plains town of 500 souls. An outstanding student and debater, he won a scholarship to Dakota Wesleyan University in nearby Mitchell, where the family had moved when George was aged six.

There he was twice elected class president and won a state public speaking contest with a speech entitled "My Brother's Keeper", a fervent statement of an individual's responsibility to his fellow human beings. In Mitchell, too, he met another student, Eleanor Stegeberg, whom he married. But the war intervened, cutting short his studies as McGovern signed up with the air force. His exploits, carrying out 35 missions with a B-24 bomber squadron based in liberated Italy, made him a military hero, and a protagonist of historian Stephen Ambrose's bestseller The Wild Blue: The Men and Boys Who Flew the B-24s over Germany. McGovern nicknamed his plane "The Dakota Queen", in honour of Eleanor. Ambrose wrote not only of the young man's skills as a pilot, but also of the extraordinary affection in which he was held by his crew.

The fighting over, McGovern went home to complete his undergraduate degree before gaining a Masters and doctorate in American history and government at Northwestern University in Chicago. Already, though, he was starting to become active in the South Dakota Democratic party, and gradually the lure of full-time politics became irresistible.

In 1956 McGovern was elected to the first of two terms as a Congressman, quickly becoming an expert on agricultural issues. Four years later he tasted serious defeat for the first time when he ran for the Senate against the incumbent Republican Karl Mundt, whom McGovern detested for his support of the red-baiting Joe McCarthy. "It was my worst campaign," he would say, "I hated my opponent so much I lost my sense of balance." Appointment by President Kennedy as director of the Food for Peace programme was only limited consolation.

In 1962 McGovern was more successful, winning South Dakota's other Senate seat. But it was his opposition to the Vietnam war, rather than his farm expertise, that turned him into a national figure. McGovern did vote for the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin resolution that led to an escalation of the war, but within a year he was describing Lyndon Johnson's carpet bombing strategy as "a policy of madness".

If Vietnam was an affront to McGovern's conscience, the death in June 1968 of his friend Robert Kennedy – to whom McGovern had spoken by phone minutes before RFK's assassination in Los Angeles – hit home equally hard. In August, two weeks before the Democratic convention opened in Chicago, McGovern declared his own candidacy for the nomination. But he secured only 146 votes in the roll call, far behind vice-president Hubert Humphrey, whom he subsequently endorsed.

After Humphrey lost the 1968 election to Nixon, McGovern emerged as a prominent party figure and, amid the growing polarisation of the country over Vietnam, almost inevitably as a contender for the party's 1972 presidential nomination. Helping him were changes in party rules after the tumultuous Chicago convention, reducing the clout of old-style powerbrokers and enhancing the role of primaries in the nominating process.

One by one other rivals dropped out. Ted Kennedy, the opponent Nixon feared most, was undone by Chappaquiddick, while Maine's Senator Ed Muskie, the establishment favourite, imploded in the early primaries. That May, moreover, a gunman put stop to George Wallace's ambitions. Running a strong grassroots campaign, McGovern secured the nomination.

His platform was the most liberal in modern Democratic history, promising an immediate withdrawal from Vietnam ("I'm fed up to the ears with old men dreaming up wars for young men to die in," he declared), a $30bn cut in defence spending, and calling for a guaranteed annual income for all Americans. But the convention in Miami was a shambles. Proceedings so overran that McGovern ended up delivering his acceptance speech at 3am, and the actress Shirley MacLaine cheerily described California delegates, of whom she was one, as resembling "a couple of high schools, a grape boycott, a Black Panther rally and four or five politicians who walked in the wrong door."

Even more damaging, if possible, was the fiasco of McGovern's vice-presidential choice, Senator Tom Eagleton of Missouri, who was forced to withdraw after admitting he had a history of severe depression. After much dithering, McGovern dropped Eagleton from the ticket. By then however, damned either for waiting too long before taking action, or for having not had the courage to see the storm out, he had squandered much of his reputation for honesty and straight dealing, which were among his main political assets.

McGovern replaced Eagleton with Sargent Shriver, brother-in-law of JFK and a former director of the Peace Corp and US ambassador to France. Shriver was an excellent candidate, but the pattern was already set. The Watergate scandal was yet to have an impact, and Nixon ran a meticulously organised "Rose Garden" campaign, rarely straying from the White House and claiming he was focussing on the nation's important business.

On 7 November 1972 Nixon carried every state except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia, winning 60.7 per cent of the popular vote. McGovern managed to joke about the disaster: "We opened the doors of the Democratic party, and 20m Democrats walked out," he told a dinner of political journalists a few months after the debacle.

McGovern's star thereafter quickly faded. In 1980 he lost his Senate seat, and by the time he launched a third and futile White House bid four years later, he was a symbol of all that made the Democratic party (with the sole and Watergate-influenced exception of Jimmy Carter) virtually unelectable in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1972, an idealistic anti-war law school graduate called Bill Clinton was a worker on the McGovern campaign. By the late 1980s, when the now Governor Clinton was trying to shift the party towards the centre as he prepared his own run for the Presidency, McGovern was a virtual unmentionable. By then, however, the former candidate had left politics for good to devote himself to third world issues, above all food and nutrition. In 1998 Clinton, by now President, appointed McGovern as US envoy to the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation in Rome.

In October 2001 he became Global Ambassador for Hunger on behalf of the World Food Programme, the UN agency he helped found back in his Kennedy administration days, and which had grown into the world's largest humanitarian aid agency. In his book Ending World Hunger in Our Time, he laid out a strategy to end world hunger with programmes that fed and educated poor children.

At the age of 72, McGovern was scarred by family tragedy when his daughter Terry, a homeless alcoholic, froze to death in the winter of 1994. He poured his grief into a moving memoir, Terry: My Daughter's Life And Death Struggle With Alcoholism, with whose proceeds he established the McGovern Family Foundation to raise funds for alcohol research.

George Stanley McGovern, politician and diplomat: born Avon, South Dakota 19 July 1922; Congressman for South Dakota 1957-61, Senator 1963-1981; Democratic party Presidential nominee 1972; Presidential candidate, 1984; President, Middle East Policy Council 1991-1998; US Ambassador to FAO, Rome 1998-2001; married 1943 Eleanor Stegeberg (one son, four daughters, one deceased); died Sioux Falls, South Dakota 21 October 2012.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies