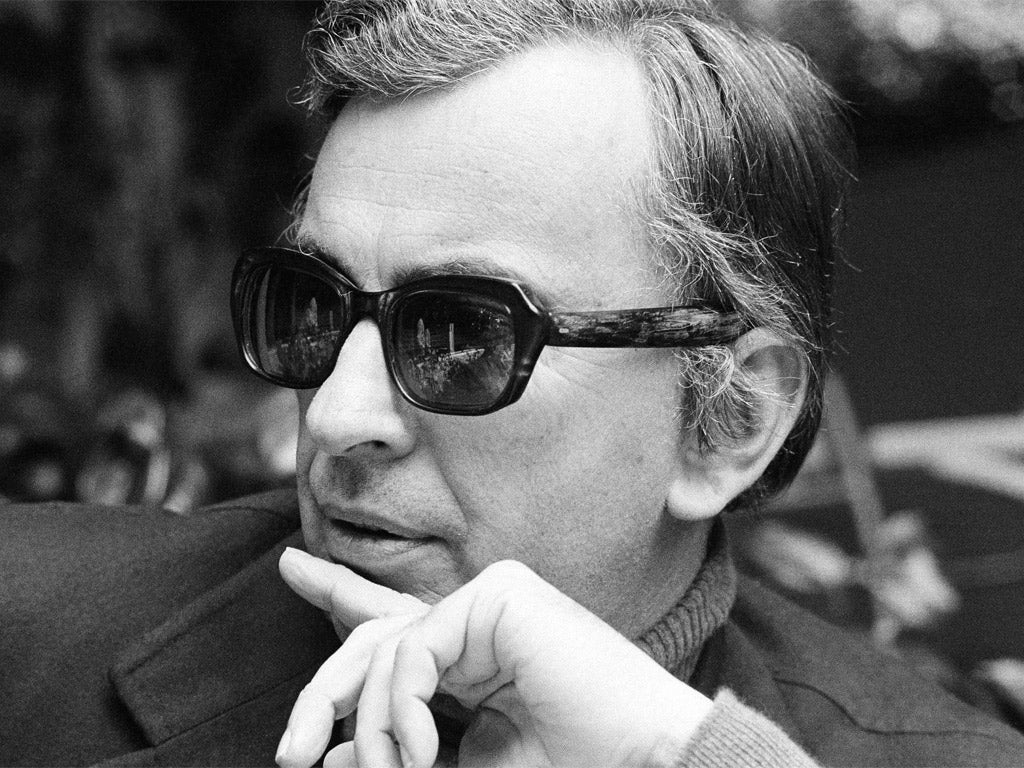

Gore Vidal: Writer and commentator who bestrode the cultural life of America for 50 years

Gore Vidal was the author of some three dozen novels, hundreds of essays, several plays and dozens of screenplays for the movies and television. For recreations, his Who's Who entry simply states, "As noted above".

And, now that he is unavailable for any more of those television conversations and cannot be tempted to the telephone for a droll remark about some fresh scandal, it is probable that a fair proportion of those volumes will shake themselves free of the suave carnival which was his earthly presence and be assured of that classic status over which this most confident of men could not help but fret. Askance though he would so often look at the country of his birth, his was a quintessential American life, energy incarnate, the continent at its best, the Old World galvanised by the New.

He was the son of the handsome and athletic Eugene Vidal, whose family, of Austrian roots, reached South Dakota in the late 19th century.Sport and engineering took him to West Point, where he married Nina Gore, a flirtatious girl whose mother had enough on her hands in looking after a blind husband, TP Gore. Of Anglo-Irish origins, he was sufficiently canny, in his career as a Democrat Senator to withstand such allegations as impregnating a girl who was herself blind.

These worlds behind Gore Vidal were one foundation of his future work. The blind Senator's love of books was a prime influence upon a boy who for all his future bravura was palpably disturbed by a household in which his mother's character proved so at odds with her husband's: she relished parties, he was far happier at the controls of an aeroplane. In time, their son would contrive a life in which the convivial and the solitary were combined to productive account: novels which he divided into historical and "inventions". One need not dwell upon the psychology to which he was so averse to see that these twin modes of fiction owe something to the solid yet flighty atmosphere of his upbringing.

A succession of schools and camps did not faze Vidal but brought a lifelong ability to live on the move, balanced by comfortable bolt-holes. His father was romantically occupied with Amelia Earhart, while his mother soon saw hope of financial salvation in Hugh Auchincloss; news of the imminent nuptials was relayed to Vidal by a teacher. He sought solace in a dog (another lifetime's passion), in reading Gone With The Wind (Clark Gable would be another of Nina's lovers), and scripting Civil War events enacted by hundreds of toy soldiers. His independent spirit meant that he was not one of nature's dutiful pupils, but had that autodidactic spirit which his essays later encouraged in others.

He was haunted by Jimmie Trimble, whom he met at 12. A crush, as Vidal realised, but such that news of his wartime death was so traumatic that he could not help but suppress it, gradually acknowledging it in fiction before making it the emotional core of a memoir, Palimpsest (1993), work on which brought him in contact with Trimble's 90-year-old mother – and to make arrangements for his own burial as close as possible to Trimble's grave at Rock Creek Park, Washington DC.

His school in Los Alamos was taken over by those working upon the atomic bomb. His next school, the high-toned Phillips Exeter Academy in New England, brought a growing skill at debate. Less public was the assiduous writing of stories and poems, while at home, he began a romance with a girl, Rosalind Rust. Vidal pondered engagement, but fought shy of marriage, certain that he was equally attracted to men. Freewheelingly disciplined, he could lead life without a script.

With Army service in 1943 he was despatched to the Second Air Force Rescue Boat Squadron. Unlike Jimmie Trimble he did not see action and, with $10,000 salted away, he was invalided out by rheumatoid arthritis. This was eased by the sun of Beverly Hills, where he struggled with a novel about that wartime experience.

A biographer of Amelia Earhart interviewed his father, who mentioned his son's work on a book. This brought interest from the publisher Dutton, who was even willing to publish his poems. These were put on perpetual hold when the novel's block was broken by a chance meeting on an East Hampton beach with a novelist whom he much admired, Frederic Prokosch, and by watching Boris Karloff in Isle of the Dead: the performance inspired energy within himself. The taut Williwaw (1946), not afraid of a Hemingway touch, retains its power.

He was rapidly fêted, but literary life brought a recurrent need to retreat from cocktails and laughter, from flirtation with Anais Nin and jibes about Truman Capote – and especially from temporary supervision of the factory where his father manufactured plastic bread-trays. He duly upped for Guatemala City, where he established a home, worked hard and almost died, before returning to New York and publication of The City and The Pillar (1948), a best-selling account of homosexual life which Vidal believed led to his sidelining by the New York Times; even so, it fascinated Kinsey and Thomas Mann, and his father's cautious admiration hinted at such youthful flirtations of his own.

An affair drew him into the ballet world; and friendships grew with, among others, Tennessee Williams, the woman – a relation by marriage – who would marry John F Kennedy, Christopher Isherwood, Paul Bowles, and, later, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. "I am mesmerised by the tributes to my beauty that keep cropping up in the memoirs of the period," he recalled. "At the time, nobody reliable thought to tell me."

Central to his life was Howard Austen, whom he met at the louche Everard Baths. Their relationship was always a companionable one – bedrock rather than bed – and the droll Austen was his mainstay. An appalling letter about him in 1957 from Nina made Vidal have no more communication with her until her death in 1978.

Serious fiction could hardly sustain somebody who had bought a fine, Greek Revival house on the Hudson, and its restoration was partly funded by three rapid thrillers under the name of Edgar Box whose witty asides are seen to best advantage in Death in The Fifth Position (1950): the title refers to the ballet world, which he knew intimately. For a decade, he was most associated with lucrative, live-television plays, notably Dark Possession. One was adapted for the stage as Visit To A Small Planet, then bought by Hollywood for $300,000, rather more than he had received for Messiah (1951), a novel of the future which found an audience among the young in the 1960s, and The Judgment of Paris (1953), a luxuriant account of Europe through American's eyes.

Both of these are set in relief by A Star's Progress (1950), written – in sedulous secrecy – as Katherine Everard. No money-spinner, alas, it is a spiritedly preposterous tale of the hard-pressed daughter of a circus lion-tamer. Her body becomes her passport, even to the bed of royalty and a Hollywood studio; the price is a lonely death with a bottle beneath a revolving fan in a cheap hotel down South. All this – its tone that of a classical pianist breaking out into a spot of boogie-woogie – anticipates Myra Breckinridge.

More lucrative was Ben-Hur, whose star, Charlton Heston, would not only, unawares, find himself enacting a crucial homosexual twist to the plot but ever after be the object of taunts by Vidal, whom the movie had so sustained that, by the early '60s he was in a position, with the support of Eleanor Roosevelt and John F Kennedy, to stand for Congress under the slogan of "You'll get MORE with GORE". Not his most elegant sentence, but certainly true. A significant proportion of the vote was not enough to win, but his political play The Best Man is masterly. He would make other political forays, by then out of favour with the Kennedys, a clan he dubbed "The Holy Family" in one of the essays for which he had become as well known as he was for the fiction to which, now his own master, he returned.

If Julian (1964) marked one extreme of his historical range and the '40s world of Washington DC (1967) the other, he was always seeking fresh, even fantastic territory. In Rome, where he settled for much of the year, he developed that vision of America which became Myra Breckinridge (1968). Time has made sex-change operations as commonplace as tonsillectomies but the vivacity of the language, the effortless references to arcane movie scenes, draw one into this tale of a New Woman whose history is a poignant amalgam of vulgar dreams and knife-sharp realities. Never was a widow so merry, so bold as to declare that "the films of the 1940s are superior to all the works of the so-called Renaissance, including Shakespeare and Michelangelo. I have been drawn lately to the television commercial which, though in its rude infancy, shows signs of replacing all the other visuals arts", harbinger of many a Media Arts course.

Through Myra, he observed that the Forties were "the last moment in human history when it was possible to possess a total commitment to something outside oneself. I mean of course the war..."

A sequel, Myron (1974), lacked that brio, despite adopting the names of Supreme Court judges for body parts "such as 'her powells', 'his rehnquist'). Overshadowed by Myra Breckinridge was the endlessly fascinating "novel in the form of a memoir", Two Sisters (1970) whose first page asserts: "after a quarter-century of publication, I have learned never to discuss my work with other writers. It excites them too much." Time again switches between the 1940s and the '60s, with additional recourse to the events of 356 BC and the Persian Wars.

It could hardly be as popular as Burr (1973), with which Vidal mixed real and fictional characters in a chronicle of America which, spurred on by the advance of $1 million for a novel about Lincoln (1994), gained the overall title "Narratives of Empire". Across peaks and doldrums, it worked forwards to link up with Washington DC and an extended coda in the overlapping The Golden Age (2000), a title shot through with the irony and esteem in which Vidal held the era that was his youth.

By this time, he and Howard Austen had exchanged Rome for a large house, La Rondinaia [The Swallows' Nest], high above Ravello. But he was often on the move, not least for appearances, of a Wellesian hue, in such movies as Bob Roberts, and his own Billy the Kid (a subject which had fascinated him since childhood). To overlook the likes of Princess Margaret, Claire Bloom, Susan Sarandon, Chips Channon and Greta Garbo – or disputes with Norman Mailer and William Buckley – might look rash; equally, his opposition to the Israeli lobby within America.

He remarked, "I had never wanted to meet most of the people that I had met and the fact that I never got to know most of them took dedication and steadfastness ... If you have known one person you have known them all. Of course, I am not so sure that I have known even one person well, but, as the Greeks sensibly believed, should you get to know yourself, you will have penetrated as much of the human mystery as anyone need ever know."

That Vidal penetrated further than many became apparent with two later novels, Duluth (1983) and Creation (1981), which are perhaps his best. The former briskly twists and turns upon America's increasing suburbanisation; while, at a tireless, stately pace, the narrator of Creation, Cyrus, a Persian diplomat in the 5th century BC, travels much of the known world; Mary Renault described it as taking off "with peacock wings", an apt metaphor for its fine show of delightful erudition.

Vidal spoke in perfectly constructed sentences, but was none the less one for the bold stroke, and if, in his fiction, that resulted in the lumpen (Hollywood, 1989) or wayward (Live From Golgotha, 1992), he leaves behind so much that he is considerably more than the man who said, "whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies".

In his last years, he took to travelling across America and Europe, where he attracted large audiences which relished the conversation at which interviewers had no trouble in encouraging him. Existing in typescript is Letters of Gore Vidal, edited by the biographer with whom he fell out. Its appearance would be a delight.

Christopher Hawtree

Gore Vidal, author: born West Point, New York 3 October 1925; partner to Howard Austen; died Hollywood Hills 31 July 2012.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies