Hercules Bellville: Much-loved film producer who worked with Polanski, Bertolucci and Antonioni

Hercules Bellville devoted his life to the cultivation of friendship and the making of films. He was a very considerable film scholar and in terms of intellectual history he should be classed with his Oxford contemporaries and great friends Laura Mulvey, Jon Halliday and Peter Wollen as among the first in England to register the full impact of that French cinephilia which was to give birth to the New Wave. But Bellville’s scholarship was from the very first to be devoted to the making of films. A list of the directors with whom he worked is also a list of some of the finest directors of the past 40 years.

Unusually, and perhaps because of his great privilege – a wealthy family, extraordinary good looks and a charm which was all the more engaging for being extremely hard-edged – Bellville never sought the limelight. His credits are remarkable – second unit director on Roman Polanski’s Tess and Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger, producer credits on Jonathan Glazer’s Sexy Beast and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers – but he was supremely uninterested, even embarrassed, by them. What mattered to him was to be using his extraordinary skills and knowledge to help talent and grace find form in the most powerful and democratic of artistic mediums.

Perhaps the single most important thread in a life woven of extraordinary friendships was the Peploe family.

Hercules met the eldest daughter, Clare, very early at Oxford where he was reading French and Spanish at Christ Church. His parents had been divorced; his father, Rupert, was a test pilot and his mother Jeanie (nee Fuqua) was the daughter of a diplomat.

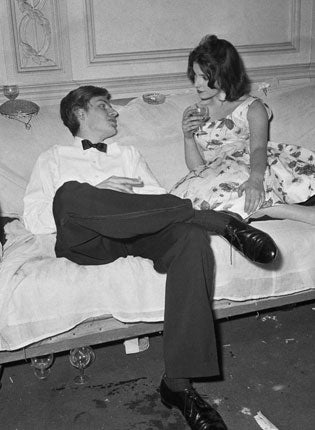

Hercules became a devoted admirer of Clare’s mother the painter Cloclo Peploe, a lifelong friend and collaborator with her brother, the director and screen-writer Mark, and the boyfriend of the younger daughter, Chloe, through much of the Sixties. It must be said that a beautiful girlfriend was one of Bellville’s trademarks, although it was also typical that when the affair had ended the friendship endured. He was a regular visitor to the Peploe villa San Francesco in Florence in the early Sixties and a fellow guest records her astonishment at meeting this impossibly beautiful and impossibly blond young man for the first time.

Bellville’s first break came when Polanski hired him as a runner on his 1965 film Repulsion (the one credit he did claim with pride was that it was his handwhich comes through the wall as the heroine collapses into psychosis), and he worked with Polanski and his producer Andrew Braunsberg for over a decade, following them in the early Seventies to Hollywood. From his base in the Tropicana Motel he adopted Los Angeles as one of his many home towns, returning each Christmas to what he called “the coast” to renew and recharge his friendships. His mother was American and he had been born in California, so there, as in so many other places, he considered himself a native.

Bellville was a gentleman of a new school. Independently wealthy, he would only live on what he could earn; a great dandy, he scorned expensive clothes, seeking his elegant attire in the most unlikely of chain stores. He was a product of the great democratic settlement of post-war Europe and he was as interested in talking to the assistant manager at the Grand Hotel about the rhythms of the tourist season as he was exchanging information about downtown Los Angeles with his good friend Jack Nicholson or exploring a new topic of conversation with a young child. His vast knowledge of film, art, restaurants, hotels and cities was at the service of anyone who he felt could benefit from what he knew.

Bellville finally found the ideal home for his talents when in the early Eighties he joined forces with the great British producer, Jeremy Thomas, at the Recorded Picture Company. He and Thomas formed the closest of friendships at the heart of the most daring and international of British production companies. Rapiers to each other’s foils, their merged talents formed a single powerful film intelligence at the service of Conrad’s great dictum: “Above all, to make you see”.

The list of films is staggering: from The Last Emperor through Crash to Young Adam. Even the financial failures, like Terry Gilliam’s Tideland, were films of huge ambition. Bellville’s role was twofold. In development he would deploy his vast knowledge and erudition in ensuring that script and cast improved – when asked what he did, he said, “I discourage people”, but what he meant was that he encouraged them to try harder and to aim higher. Then, when the filming began, Thomas did not have to spend a minute worrying whether anybody, from the most famous of international stars to the gruffest of grips, felt unappreciated or unloved. “Herc” was everywhere, dispensing witty reassurance, tiny presents and always talking about films. That esprit de corps so crucial to almost any successful film was ensured on any project with which Bellvillewas associated.

At the annual festival of Cannes, Bellville energised and enthused from dawn to dusk to dawn again. Here, he and Thomas could meet with the full range of his international contacts, here he could deploy his perfect Spanish, his fluent French spoken with a cut-glass English accent and littered with witty anglicisms, and his considerable Italian. Here he could usher young film-makers from all five continents into meetings where he would immediately make everyone at ease.

Here he could parry wits with that other great multilingual diplomat of recent European cinema, Marie-Pierre Hauville, the festival’s foreign minister.

It is unsurprising that so committed an internationalist was hit so hard by the events of 11 September 2001. This outrage seemed to set back for decades everything that Hercules had believed in and devoted his life to. He suffered what the French call a dépression nerveuse and many of his friends wondered whether he would ever recover. However, in 2003, in his much loved Mexico, he met Ilana Shulman and she, who shared so many of his interests in cinema, art and travel, brought a tenderness to his life which meant that his final years, even when his lung cancer was diagnosed, were full of happiness. For a man who insisted that every dinner had a placement and every journey a movement order, it was natural that he should make final arrangements. He had been educated by the Benedictines at Ampleforth school and as the end approached he married Ilana and received the last rites of the Roman Catholic church.

Colin MacCabe

Hercules Bellville, film producer: born San Diego, California 18 June 1939; married 2009 Ilana Shulman; died London 21 February 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies