John Raines: US whistleblower who burgled the FBI to highlight J Edgar’s Hoover’s war on civil rights movement

The professor of religion admitted to breaking the law many years later. ‘But those of us who were active in the civil rights movement of the early Sixties had learned to differentiate between breaking a law and committing a crime’

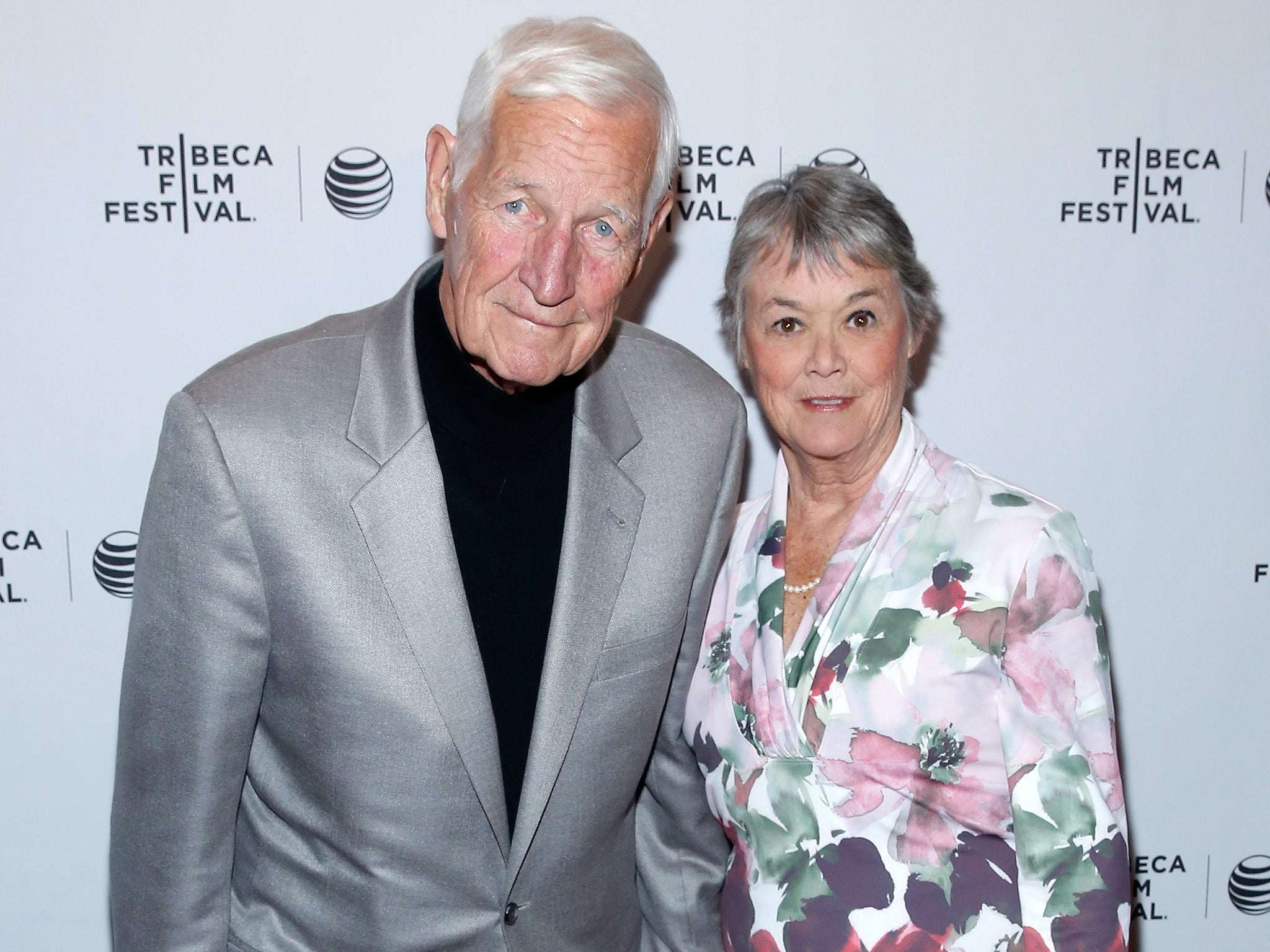

For 43 years John Raines lived with an explosive secret. On 8 March, 1971, he and his wife, Bonnie Raines, then the parents of three young children, joined six other conspirators who broke into an FBI office in suburban Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and burgled it.

The cache of documents they stole revealed a sweeping campaign of intimidation by the FBI, against civil rights and antiwar activists, communists and other dissenters.

Raines was a professor of religion at Temple University and an ordained Methodist minister. The FBI was then led by J Edgar Hoover.

One now-infamous document told agents to ramp up interviews with perceived subversives “to get the point across there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox”.

Calling themselves the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI, the burglars anonymously distributed the stolen documents to newspapers. Ignoring the objections of the US attorney general of the time, and the reluctance of other newspapers, The Washington Post ran a front-page report on FBI surveillance on 24 March 1971. Other news accounts followed, along with public outrage, and eventually the formation of the Church Committee of US senators that uncovered widespread abuses in the country’s intelligence agencies.

Hundreds of FBI agents investigated the break-in but failed to identify the burglars, who, if apprehended, would have faced years in prison. Only years after the fact – long after the statute of limitations had expired – did Dr Raines reveal his identity to Betty Medsger, the Washington Post journalist who had broken the news of the stolen documents.

In 2014, Medsger published a book-length account of the story, The Burglary: The Discovery of J Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI. In an interview, she described the actions of Raines and his wife as “one of the most powerful acts of resistance in the history of the country”.

Her account helped make Raines, by then in the final years of his life, a hero to civil libertarians – he has died in Philadelphia aged 84.

Raines credited his wife with having drawn him into activism along with her. “I was dragged along by her enthusiasm,” he once told the Los Angeles Times – an account she seemed to confirm. Once she said “he had more sleepless nights” than she did. But Raines also had a long history of civil rights work.

He had participated in the Freedom Rides to challenge segregation in interstate transport and marched in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, when state troopers assaulted protesters with clubs and tear gas – the march was led by Martin Luther King.

Raines was angered both by Hoover’s antagonism to the civil rights movement and his apparently untouchable status.

“Nobody in Washington was going to hold him accountable,” Raines told America’s National Public Radio in 2014. “It was his FBI, nobody else’s.”

With his wife, Raines had broken into draft board offices to disrupt the Vietnam War draft. But no act of civil disobedience was as daring as the break-in at the FBI office in the town of Media, Pennsylvania.

The Raineses were recruited by the physics professor William C Davidon. “After the chin came off the floor and we started talking about it, it seemed more and more plausible,” Raines recalled.

The conspirators plotted the break-in from the Raineses’ attic. Bonnie Raines, who ran a day-care centre, managed to gain entry and recce the FBI office in advance by posing as a college student seeking information about employment opportunities. In the event of their arrest and imprisonment, the couple arranged for Raines’s brother to care for their children.

“We have a double responsibility,” Raines told CNN in 2014, “yes, as parents to our children, but also as citizens to the nation those children are going to live in and have children in.”

The group scheduled the break-in to coincide with the boxing match in which Joe Frazier would defeat Muhammad Ali – astutely predicting that the momentous sporting event would distract neighbours of the FBI office as well as police. Without much trouble, they used a crowbar to break in, then carried out more than 1,000 files in suitcases. Raines drove the getaway car to a Quaker farm, where they donned gloves and began combing through the documents.

“Within an hour, we knew we hit the jackpot,” Raines recalled.

The documents contained early evidence of COINTELPRO, short for Counterintelligence Programme, which, the FBI later acknowledged, was “rightfully criticised by Congress and the American people for abridging First Amendment rights”.

Among other revelations, the materials showed that the FBI had systematically surveilled and harassed African Americans, particularly civil rights activists. In one instance, it had attempted to blackmail Martin Luther King Jr by threatening to reveal his extramarital affairs if he did not commit suicide before collecting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

The Church Committee report, issued in 1976, found that “too many people have been spied upon by too many government agencies and too much information has been collected”.

The extent of the abuses confirmed to Raines the rightness of what he and his collaborators had done. But years later, reviewing Medsger’s book in The New York Times, history professor David Oshinsky was among those who questioned the burglars’ methods.

They “committed a serious felony on the suspicion that a government bureau was engaging in nefarious activities; they had no evidence in hand. Would their actions have been equally heroic had they come up dry?” he wrote.

He added: “The burglars are portrayed as devoted followers of civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance. But one of the tenets of such behaviour is to take responsibility for the act. I don’t recall Thoreau [author of the 19th-century tract on civil disobedience] adding: ‘Catch me if you can’.”

Raines wrote his reply to the newspaper.

“We certainly broke the law, perhaps many laws,” he said. “But those of us who were active in the civil rights movement of the early Sixties had learned to differentiate between breaking a law and committing a crime.”

John Curtis Raines, the son of a Methodist bishop, was born in Minneapolis. He received a bachelor’s degree in English from Carleton College in Northfield, Minneapolis, in 1955, and a doctorate in theology from Union Theological Seminary in New York in 1967. He was a professor of religion at Temple for more than 40 years.

He is survived by his wife of 55 years, Bonnie, born Bonnie Muir, their daughters, Lindsley and Mary, and sons Nathan and Mark.

Filmmaker Johanna Hamilton released a documentary about the break-in, 1971, in 2014. Raines’s story had particular resonance at the time; the previous year, intelligence contractor Edward Snowden had leaked a massive trove of documents about surveillance by the National Security Agency. Snowden later obtained asylum in Russia.

Asked in 2014 if he had a message for Snowden, Raines replied, “From one whistleblower to another whistleblower – Hi!”

John Raines, academic and civil rights activist, born 27 October 1933, died 12 November 2017

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies