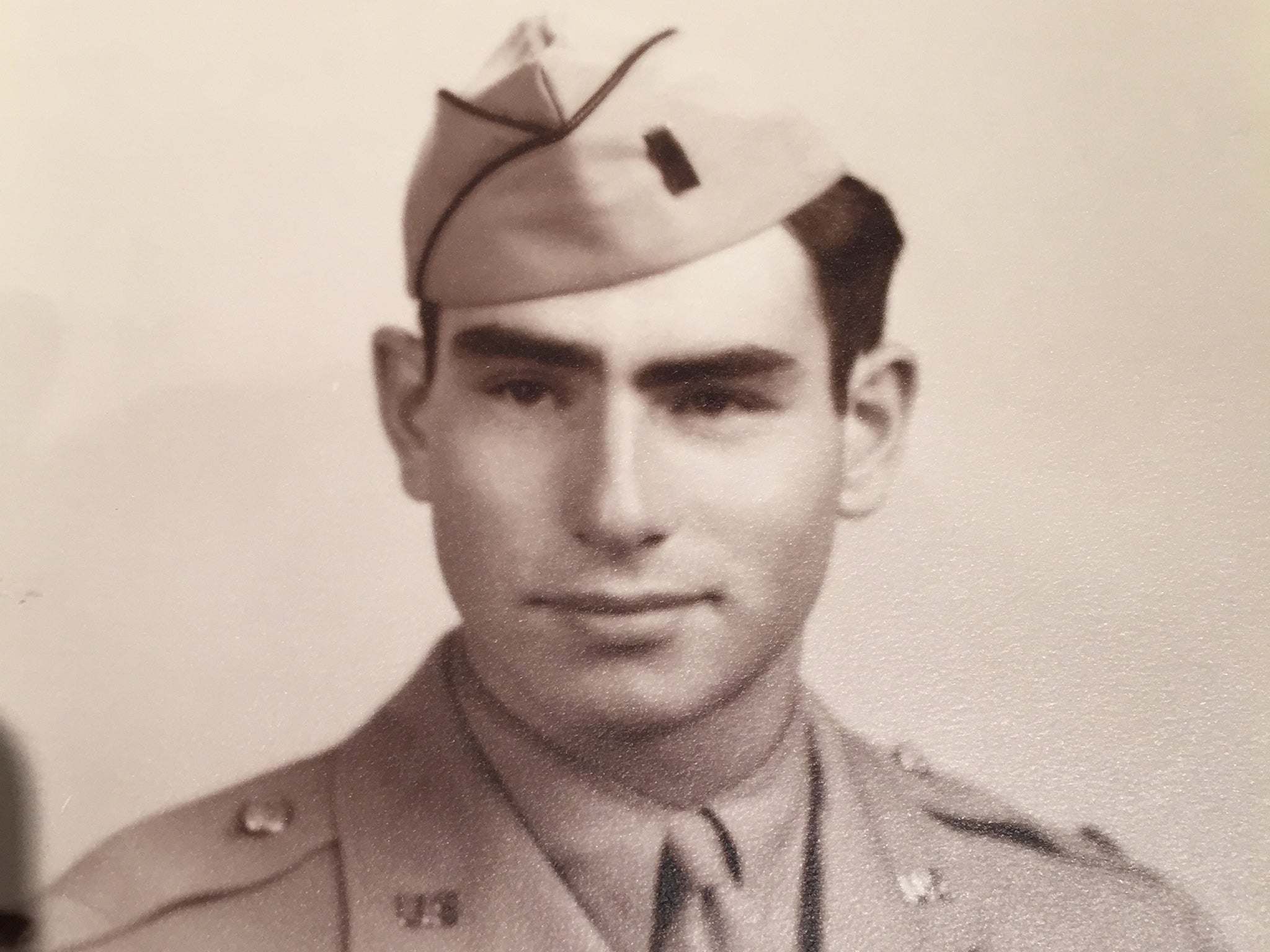

Lieutenant Robert Weiss: Soldier whose expertise and valour in calling in artillery strikes helped the allies win the Second World War

Weiss's heroics won him a Silver Star and two Purple Hearts, while France awarded him a Croix de Guerre and named him Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur for his role in the nation's liberation

On 6 August 1944, two months after D-Day, 700 men of the US 30th Infantry, “Old Hickory” Division, found themselves on a hill in Mortain, Normandy, surrounded and vastly- outnumbered by three counter-attacking Panzer tank divisions and thousands of elite SS soldiers. On one of the Americans' two radios, 21-year-old Second Lieutenant Bob Weiss, a field artillery forward observer, called his command HQ with five words: “Enemy north, south, east, west.''

The ensuing six-day Battle of Mortain altered the course of the war and Weiss played a pivotal role while half his 700 comrades were killed or wounded. After the other radio ran out of batteries, it was he who called in allied artillery strikes on the surrounding Germans, most of them a few hundred yards from his position on top of Montjoie, or what the Americans called Hill 314.

His binoculars became one of the most important single “weapons” of the war, helping halt the German counter-thrust – Operation Luttich – designed to drive the allies back, in Hitler's words, “recklessly to the sea.” Weiss and his comrades, however, held Hill 314 under continuous fire for six days, while the artillery shells he called in destroyed around 100 tanks. The Germans were forced to give up their attempt to intercept the allied advance and made a panicky retreat which allowed the allies to push forward through the Falaise Pocket, a key breakthrough in the war.

In all, Weiss called in 193 artillery strikes in six days, sometimes at the rate of every 15 minutes. “My binoculars soon became a gun sight,” he recalled. “When I shouted 'Fire Mission' it was as if I were tensing my trigger finger. 'Crow, this is Crow Baker 3. Fire mission, enemy vehicles. Tanks ... Strong enemy force ... men milling about. Large counter-attack ..... tanks in draw.'” With no specific front line, Weiss and his comrades engaged in hand-to-hand or bayonet combat with German soldiers they encountered at night, sometimes while drawing water from the nearest well.

Weiss's heroics won him a Silver Star and two Purple Hearts, while France awarded him a Croix de Guerre and named him Chevalier de la Legion d'Honneur for his role in the nation's liberation. His hilltop foxhole gave him a 360-degree view unavailable to any of the allied or German generals. His position also made him a constant enemy target, but he was one of the 357 of the 700 Americans on the hill who walked down unaided at the end of the battle, many carrying bodies.

As the defenders' supplies had dwindled, Weiss co-ordinated artillery fire on his own positions – non-explosive shells normally used as smoke bombs or propaganda leaflets, but this time filled with medical supplies. “The effort was a total flop because of the high-velocity start and the sudden impact,” he recalled. His coordinates also helped RAF Typhoon fighter-bombers and US P-47 Thunderbolt fighters hit the Germans from the air. “By some miracle, our radio batteries last to the end,” he wrote in his book Fire Mission! (first published as Enemy north, south, east and west), hailed by many war historians as one of the finest personal accounts of battle during the Second World War.

A month after Mortain, Weiss was wounded in Belgium and evacuated to a hospital in newly liberated Paris. He was back on the front lines for the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes until the end of January 1945, and for the crossing of the Rhine two months later. Just after the end of the war, he returned to Paris – “probably Awol,” he said – and visited the Louvres on 10 July, the day it reopened. “There, on a counter, where you could actually touch it, was the Mona Lisa.” He said he took her enigmatic smile as surprise that he had survived the war.

Robert Lincoln Weiss was born in Haverford, Pennsylvania in 1923, the son of a Hungarian Jewish couple who had emigrated at the end of the Great War before pro-Fascist persecution swept through Hungary. He graduated from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, just before the US entered the war, and he joined the army in 1943, aged 20.

He landed on Utah beach, Normandy, on D+7, 13 June 1944, as an Artillery Forward Observer for the 230th Field Artillery Battalion. By the time he reached Hill 314 he was one of two artillery observers attached to E (Easy) Company, 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, the division nicknamed “Old Hickory” in the US but soon dubbed “Roosevelt's SS” by a respectful German enemy.

After the war, he attended law school at the University of Chicago before starting a career as an attorney in Portland, Oregon, which would go on for 50 years. He continued to give lectures on his war experiences to universities and historical societies, also writing fiction, plays and poetry. He returned to France several times; he was greeted as a hero at last year's D-Day 70th anniversary celebrations.

His 1945 citation for the Silver Star read, in part: “Lieutenant Weiss' great heroism [was] materially responsible for trapped units being able to hold out against overwhelming odds. He fearlessly exposed himself, in moving from one observation post to another, often deliberately drawing enemy mortar, artillery, and small arms fire so that he could better see the effect of artillery fire on the enemy. His gallantry aided greatly in turning back several counter-attacks.”

In recent years, Weiss had been in a highly publicised dispute with the US writer Stephen Ambrose, author of the book Band of Brothers, which became a hit TV series. The dispute was over Ambrose's 1997 book Citizen Soldiers, which leant heavily on Weiss's recollections of the Battle of Mortain. Because of Ambrose's reputation, Weiss had sent him a manuscript of his memoir Fire Mission! to help him get it published. According to Weiss, Ambrose said he couldn't – but he did use much of Weiss's material, credited only in small print. Ambrose's reputation suffered, if only temporarily.

Bob Weiss is survived by his adopted children Charlie and Lucy and by his long-standing companion, Norma Leszt.

Robert L Weiss, soldier and lawyer: born Pennsylvania 4 April 1923; married three times (two adopted children): died Portland, Oregon 26 August 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies