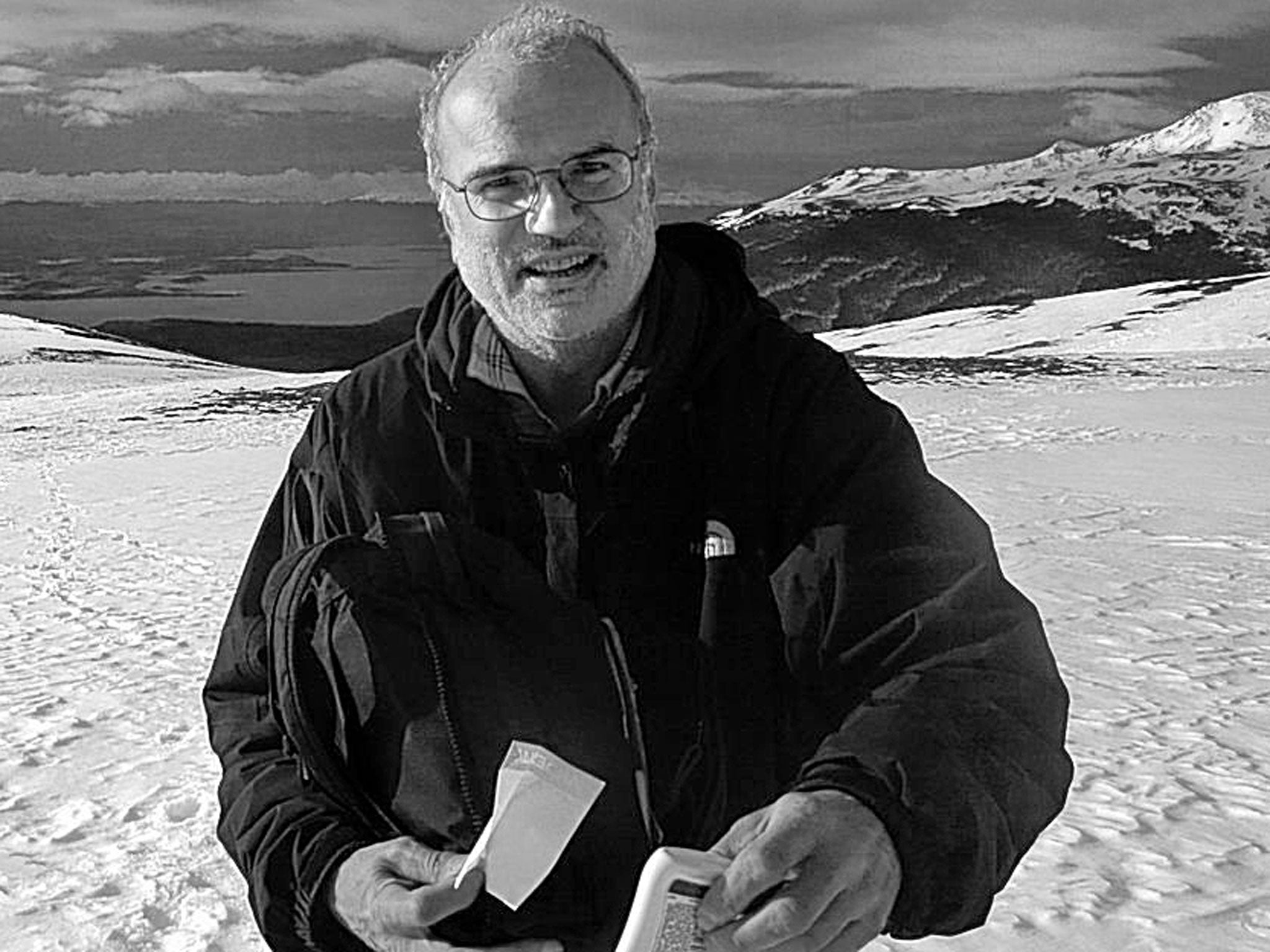

Michael Jacobs: Art historian and Hispanophile who changed direction to become a funny, idiosyncratic and acclaimed travel writer

Michael Jacobs was Britain's foremost living writer on Spain. He has now joined that pantheon of British Hispanophiles that includes Gerald Brenan, George Borrow and Richard Ford, saluted by his contemporary rivals, such as Chris Stewart, Hugh Thomson and Jason Webster, and lauded in his adopted literary homelands of Spain and Latin America. He died at the age of 61, having been diagnosed three months previously with kidney cancer on the day his last book was up for the Dolman Travel prize – after which he drank his friends and casual acquaintances of that night under the table of a Soho basement club. He never suffered from a hangover or owned a car and he completed 24 books in a 34-year career.

He was both Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, part of that rare breed of scholar-gypsies these islands have incubated, like Walter Starkie and Paddy Leigh-Fermor. On one hand he was a well-travelled, Courtauld-trained art-historian, fluent in four languages and a favourite student of Anthony Blunt. On the other he was a Rabelaisian partygoer, a man who needed four hours to lunch, who charmed his way round the world and was easily the most accomplished and joyful literary ligger of his generation.

His career can be divided into two halves; the hard-working young art scholar ferociously busy between 1979 and 1999, transformed in his mid-forties into the profane lover of Spanish street life, after which came half a dozen travel books. And although he could at times dismiss his art and architectural guidebooks as no more than an apprenticeship to travel writing, it was never that simple. I remember him confessing, with a bemused smile at the workings of the publishing industry, that it was a coffee-table book on the most beautiful villages of Provence which had been his most impressive earner. He also learned early on that the word "No" should never be articulated by an independent scholar to a publisher. He wrote for an impressive range of publishing houses before finding his spiritual home at Granta. And at the end of his life he was passionately at work on an appealing, narrow slice of art history, Velazquez's Las Meninas.

He was a brilliant communicator, whether perched at a bar, in a lecture hall, slumped across a sofa after midnight or at an international literary festival. He was also passionate about food, about the proper dignity of the table as the arena for creativity and friendship, and believing that culinary traditions are the beating heart and visible proof of human culture.

He was a kind man and a supportive friend who took on the unpaid spadework of literary life, contributing articles to journals and charities, volunteering to review, interview, translate and make introductions as well as speak at festivals, schools and on local radio. He also advised Hispanic and English publishers about which books might be worth translating. He was a friend to the Hay literary team, helping them develop their Hispanic festivals at Segovia, Cartagena and Bogota. He was also the trusted muse of Sam and Sam Clarke, whose restaurant Moro produced a series of bestselling Hispanic-Maghrebi cookbooks.

Like all real travellers, he had friendships scattered across the globe, though he made occasional attempts to gather together all these different strands under one roof, through the living theatre of a Jacobs book launch. The last one, hosted in Moro, had him apparently cooking for his closest 200 friends of that particular city and night. A Colombian band played, cocktails and wine flowed, ambassadors, psychotherapists and poets danced, while the emotional bedrock of his life, Jackie Rae, his lifelong girlfriend since he was 23 and she 19, who had turned herself into a history teacher with a razor-sharp wit) sold piles of his books at a table.

What Jacobs could not do very well was to be convincingly British. I never heard him talk about any of our national obsessions, whether gardening, horses, children's education, cars or sports. But as he explained to me, though he was educated at Westminster – and later at home in both Hackney and the Andalucian village of Frailes – he was actually a Jewish-Irish-Italian boy born in Genoa with not a drop of Spanish or English blood in him.

His Jewish grandfather had emigrated from Hull to work on the railways in Chile and Bolivia while his mother, Maria Grazia Paltrineri, had been an actress in Sicily (his father had courted her while he was working for military intelligence). She upheld a rigorously intellectual household: Michael and his brother Francis, who became a civil servant, were expected to speak Latin on Thursday evening, while on Fridays they accompanied her to the theatre. On Saturday there were guests for dinner and conversation. It always amused and bemused Jacobs that his father, who had had the same war experiences that propelled Norman Lewis to write Naples '44, contentedly worked all his life as a lawyer for an oil company.

One of my strongest memories of Jacobs is as a judge, literally dancing on a stage, glass in hand, while he addressed a forbiddingly literary audience. Without notes he succeeded in praising, analysing and dissecting half a dozen books on the shortlist before presenting an award.

His own works were at their best when Sancho Panza and Don Quixote were both allowed on stage, allowing him to craft books with a scrupulously moral backbone of inquiry camouflaged beneath his fleshy burlesque adventures, his learning worn feather-light and combined with a relentless self-deprecation. His three most idiosyncratic, funny and endearing books are In The Glow of the Phantom Palace, a Rabelaisian romp among Moorish themes and ruins, The Factory of Light, an inversion of Arcadian-myth hunting in the bewildering-enough reality of modern Spanish life, and The Robber of Memories, his last book.

This is a haunting, half-confessional journey up the River Magdalena into his parents' disintegrating minds and his own mortality, interwoven with the literary stars and political scars of Colombia, including an astonishing denouement with FARC guerillas in the mountains. It is surely a fitting swansong.

Michael Jacobs, writer: born Genoa 15 October 1952; partner to Jackie Rae; died 11 January 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies