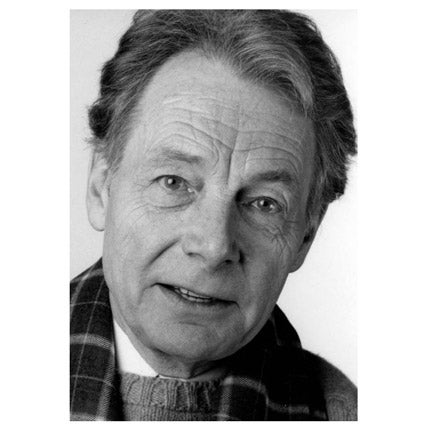

Michael Langham: Theatre director widely regarded as the spiritual father of the Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Ontario

The director Michael Langham is regarded by many in Canada as the spiritual father of the Shakespeare Festival at Stratford in Ontario.

He ran it between 1955 and 1967, overseeing its transformation from a short summer festival in a circus tent into a permanent 2,000-seat theatre. His links with it endured for more than 50 years and in 2008, when he was almost 90, he directed Love's Labour's Lost there.

In between, he ran the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, reviving its fortunes, and headed the drama division of New York's Julliard School. Throughout, there was a ceaseless blaze of passion for the works of Shakespeare; he would enrich any moment with an apt line, as though he bathed perpetually in that sublime ocean of words. And to the end he was exploring new ideas – if you telephoned him he was likely to launch immediately into "When Shylock in act one, scene three says... Do you think it might mean that..." Like a dog with a bone he gnawed at every text until it gave up new insights.

Michael Seymour Langham was born in Bridgwater, Somerset in 1919. His father was a jute merchant who died in India a month after he was born, and his mother remarried and lived in Scotland. Michael attended Radley School and was training – reluctantly – to be a solicitor when war intervened. He enlisted and was shipped to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force. Captured during the retreat to Dunkirk, he spent the next five years in prisoner-of-war camps, where he developed his determination to go into the theatre.

After emerging in 1945, he returned to Britain and led companies in Birmingham, Coventry and Glasgow, where his passion for "theatre as community" was ignited. He also met his future wife, the actress Helen Burns, and they married in 1947.

He had directed several productions at Stratford-upon-Avon when Tyrone Guthrie invited him to run the fledgling Ontario Shakespeare Festival. In 1955 he, Helen and their young son sailed across the Atlantic, where he took up the post of artistic director, returning between seasons to continue his directing career in England.

During Michael's tenure Tanya Moiseiwitsch's glorious thrust stage was built; he extended the repertoire to include Restoration drama, and led the acquisition of a second theatre, the Avon, as well as instituting North America's first film festival. Among his ground-breaking productions was Henry V, cast strikingly with French and English Canadians, which invited Canadians to embrace French Canada as an equal part of the country's cultural life. And, when the play was presented at the Edinburgh Festival, it introduced Christopher Plummer to the world. In 1964, English audiences at Chichester saw Langham's imaginative Stratford version of Timon of Athens (with music by Duke Ellington) and a revival from 1962 of his delicious and funny Love's Labour's Lost.

In 1971, Langham was asked to lead the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Guthrie had fallen on hard times, but Langham's six-year tenure revivified it. His mastery of the thrust stage was showcased in a series of superb productions, among them an Oedipus in a version commissioned from Anthony Burgess, and a School for Scandal which went on to be televised for PBS Masterpiece Theater.

From Minneapolis, Langham moved to New York and in 1979 he took up the leadership of the drama division of the Juilliard School, which he ran until 1992. From that year, almost until his death, he continued directing in New York and Canada.

Langham was tallish and lean, with a fine head of wavy hair, high cheekbones and a sharp, inquisitive nose. He spoke very fast, to match a fast-working mind and wit. Full of articulate energy, he also did a great deal of work in silence, poring over a script, stubby pencil in hand, even in the midst of a party of merry actors. His gift of concentration, he guessed, was something he had developed in PoW camp.

Professionally, he had great self-confidence and authority. His frequent instruction to actors – "when you come on stage, bring on a world", was something he practised himself without effort: he had that intangible quality, grace. But away from the rehearsal room and the office he would share his self-doubts and restless anxieties. In this context it is hardly possible to separate one's memory of Michael from Helen, his wife of over 60 years.

I first met the couple in 1963: "You came for dinner and refused to leave," they often teased me, and I saw at first-hand how discussions of the next day's rehearsal scenes would start after supper and go on into the wee hours. Michael's exhaustive knowledge of a play and its characters, his tenacious work on a text, would again and again be lit up – and sometimes turned on its head – by one of Helen's aperçus: Michael incorporated her flashes of genius into production after production, though only in later years was he able to acknowledge this.

In fact his absorption in his work became a liability in his family life. How easy it was for him to control a group of actors; how different to come home and deal with a brilliant, proud, mercurial wife, an actor denied opportunities because she was married to the artistic director. How different, too, to cope with a precocious son who was dragged back and forth across the Atlantic, and whose young life desperately lacked a centre. Michael was fiercely proud of both, but found he lacked the personal skills, and perhaps even the emotional sympathy, to create a happy home. (His son, when abused by a stranger at the age of eight, confided in William Hutt, the actor, rather than create a problem at home.)

These strains led in 1968 to a break-up with Helen. Michael then married Ellen Gorky, 30 years his junior. But they too drifted apart, and Helen and Michael began to see each other again. In 1978, they remarried. Michael retained a profound sense of remorse for his abandonment of Helen in the 1960s and refashioned his contribution to family life second time around. He learned to cook, helped with housework. He swore off cigarettes and – for many years – alcohol. He began to devote time and energy not just to his work, but to his loved ones.

Helen's career became as important to Michael as his own, and reached a climax with her 1994 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Supporting Actor in the London premiere of Miller's The Last Yankee. With equal pride he followed his son Chris's career as a comic actor and writer, having supported him in his early struggles with drugs and alcohol. And all the time he moved from production to production at Stratford and in New York.

In 1995, at 75, he became associate director of my own Atlantic Theatre Festival in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, and for four seasons directed Shakespeare, Chekhov and Ibsen. He also went public with Helen's collaboration in his work there: The Cherry Orchard, Doll's House and Uncle Vanya were all listed as co-productions. Langham's more open attitude brought other gifts to his professional life; Simon Callow, whom he directed in a marathon voyage through the Sonnets in 2008, said: "I learned to listen very carefully to everything he said: he wasted nothing. There were sermons in his slightest throwaways... It was a watershed in my work: after it, I was a different actor, and, I believe, a better one."

In the 1990s Helen was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, eventually becoming bedridden. Rather than consign her to a nursing home, Michael moved into a converted barn at his son's home in Kent and brought her home to share it. He remained by her side until his last illness.

In 2005 he was struck with a new calamity when his son Chris was imprisoned for downloading paedophile images from the internet. He had been writing a piece about a paedophile for the Bafta award-winning series Help and had stupidly looked. It was, after all, a subject of great personal significance for him and he wanted to bring to it his father's hunger for emotional truth. An appeal reduced his sentence but the subsequent years have been a continuous and humiliating agony for the family. Despite the judge's summing-up – "Paedophilia is not an issue in this case. You are not a sexual predator" – Chris was branded a paedophile in the press, and to this day is unable to take up his career.

Michael, unable to turn his back on what he saw as a monstrous injustice, embittered at the way the police and the media exploited one another to manufacture public outrage, and ashamed to be part of an England where "moralising trumps goodness," wrote a moving article for The Independent on Sunday. He said that he was prouder of this piece than of anything else he had done. It was an act of love in keeping with the Michael Langham who had newly found himself. He told me not too long ago: "I want to spend the rest of my life working to right this wrong. Chris may have been arrogant and stupid but in our profession that's never been a reason not to flourish."

Michael had a wonderful sense of fun, and brilliant deadpan way with an anecdote, his fund of stories involving many of the great names of theatre – Olivier, Gielgud, O'Toole, Richardson, Max Frisch, Paul Scofield: the list goes on. He loved to watch cricket on television and lived to hear the news that England had won the Ashes. He played endless hands of patience, and each day until his last illness, completed the three Sudoku puzzles in The Independent – saying typically: "I usually find the hardest ones the easiest."

Michael Seymour Langham, director: born Bridgwater, Somerset 22 August 1919; married 1947 Helen Burns (one son, marriage dissolved), secondly Ellen Gorky (marriage dissolved), 1978 Helen Burns; died Cranbrook, Kent 15 January 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies