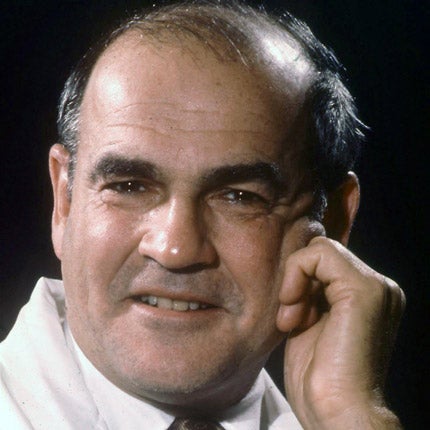

Professor Baruch Blumberg: Nobel Prize-winning researcher who discovered the hepatitis B virus

The Nobel Prize-winning scientist Baruch Blumberg discovered the killer hepatitis B virus and also developed the first anti-cancer vaccine.

Blumberg had not set out to discover the virus; as a medical anthropologist he was interested in the genetics of disease susceptibility. He wondered whether inherited traits could make different groups of people more or less susceptible to the same disease. His discovery of hepatitis B, a virus that attacks the liver and can cause cirrhosis and cancer, was discovered serendipitously rather than by design.

In 1989, he began what he described as his "second career" – a five-year tenure as Master at Balliol College, Oxford, before aiding Nasa in its search for life in the universe and the origins of life on Earth, while serving as founding Director of the Astrobiology Institute at Nasa's Ames Research Centre in California.

Baruch "Barry" Blumberg was born in Brooklyn in 1925, the second of three children to Meyer, a lawyer, and Ida. As a boy he was interested in science and while at Far Rockaway High School (whose graduates also include the Nobel physicists Richard Feynman and Burton Richter) he won a number of awards. On leaving school in 1943 he joined the Navy and finished college under military auspices.

During the war, he served as a deck officer on landing ships and was commanding one when he left active duty in 1946. He completed a physics degree at Union College, Schenectady, NY, before starting a mathematics degree at Columbia University; he soon transferred to medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, graduating in 1951. Following a Clinical Fellowship at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Centre, he obtained his doctorate in biochemistry from Balliol.

It was while at medical school that Blumberg spent several months at a hospital in Moengo, an isolated mining town in the jungle of Suriname in South America. While there, delivering babies and treating patients in isolated villages, he noted that this imported melange of races suffered from mosquito-borne diseases and poor sanitation, and his interest in infectious diseases was ignited. He undertook several public health surveys, including the first malaria survey carried out in that region.

Blumberg noted that the labourers, from as far away as India and China, lived side by side but that "their responses to the many infectious agents in the environment were very different. Nature operates in a bold and dramatic manner in the tropics. Biological effects are profound and tragic."

This study led to his first published paper and he would revisit the Tropics frequently. Initially, Blumberg was interested in establishing why some people were more vulnerable to sickness than others. In the 1950s, this simple question led him to remote villages in Africa and the Arctic, as he and his team gathered blood samples. They planned to look for genetic differences and then study whether these differences were associated with a disease.

However, without modern genetics technology, they developed a new indirect method; they turned their attention to haemophiliac patients. Blumberg reasoned that haemophiliacs who had received multiple transfusions would have been exposed to blood serum proteins that they themselves had not inherited, but had been inherited by their donors. As a result of this exposure, the immune systems of haemophiliacs would produce "antibodies" against the "foreign" proteins, or "antigens", from the donors. These antibodies from haemophiliac patients could then be used on the blood samples to identify the inherited factor or genetic difference.

On his return to the US in 1957, he continued his work at the National Institute of Health, heading its Geographic Medicine and Genetics Section until 1964. He then joined the Fox Chase Cancer Centre in Philadelphia and served as Associate Director for Cinical Research and Vice-President for Population oncology.

It was during this period, while examining thousands of blood samples, that Blumberg identified a mysterious substance in the sample of a native Australian which reacted with an antibody in the serum of an American haemophiliac. After further observations, in 1967 it was confirmed that the virus, called the "Australia Antigen", caused hepatitis B. Amazingly, the team's findings were ignored by virologists until other groups corroborated their findings.

Within two years, working with Blumberg, the microbiologist Irving Millman helped develop a blood test to detect the hepatitis B virus. Blood banks began using the test in 1971 to screen blood donations and the risk of hepatitis B infections from a transfusion decreased by 25 per cent. Over the next four years Blumberg and Millman amassed evidence of a link between hepatitis B and liver cancer and developed the first hepatitis B vaccine, initially a heat-treated form of the virus developed from the serum of those with the antigen. It was seen as the first vaccine capable of preventing a human cancer.

Initially, they struggled to find a company to produce it. "Vaccines are not an attractive product," Blumberg recalled, "and they do not generate as much income as medication for chronic disease that must be used for many years." They finally signed with a local pharmaceutical company, Merck & Co.

Since its commercial availability in late 1981, more than a billion doses have been administered. The chronic infection rate among children has plunged from 15 per cent in Taiwan and more than 10 per cent in China, for example, to less than one per cent in each country. In 1976, Blumberg shared the Nobel Prize for Medicine with Carleton Gajdusek for their work on the origins and spread of infectious viral diseases.

After a year as a visiting professor to Balliol College in 1983-84, Blumberg became its first American Master. For many years, he taught medical anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. From 1999 to 2002, he was appointed the first director of the Nasa Astrobiology Institute at Ames, lending his formidable reputation to what had been considered fringe science. Blumberg and his team were asked to address three profound questions: How does life begin and evolve? Does life exist elsewhere in the universe? And what is life's future on Earth and beyond?

While encouraging the development of instrumentation for astrobiological space probes, Blumberg recommended equal efforts in the study of earthly "extremophiles", organisms that thrive in extreme conditions. He believed such organisms may offer insights into early life on Earth, saying, "I'd be very surprised if we found something in space that would look like ET. If we find something more like a virus or a bacteria, that would be astounding enough." In 2002, he detailed his discoveries in Hepatitis B: The Hunt for a Killer Virus. He also wrote over 500 papers. In 2003, he was a castaway on Desert Island Discs.

Blumberg also enjoyed canoeing, running and playing squash, and co-owned a cattle farm in Western Maryland. "Shovelling manure for a day on my farm," he sad, "is an excellent counterbalance to intellectual work."

Baruch Samuel Blumberg; biochemist and medical anthropologist; born New York, US 28 July 1925; married 1954 Jean Liebesman 1954 (four children); died Mountain View, California 5 April 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies