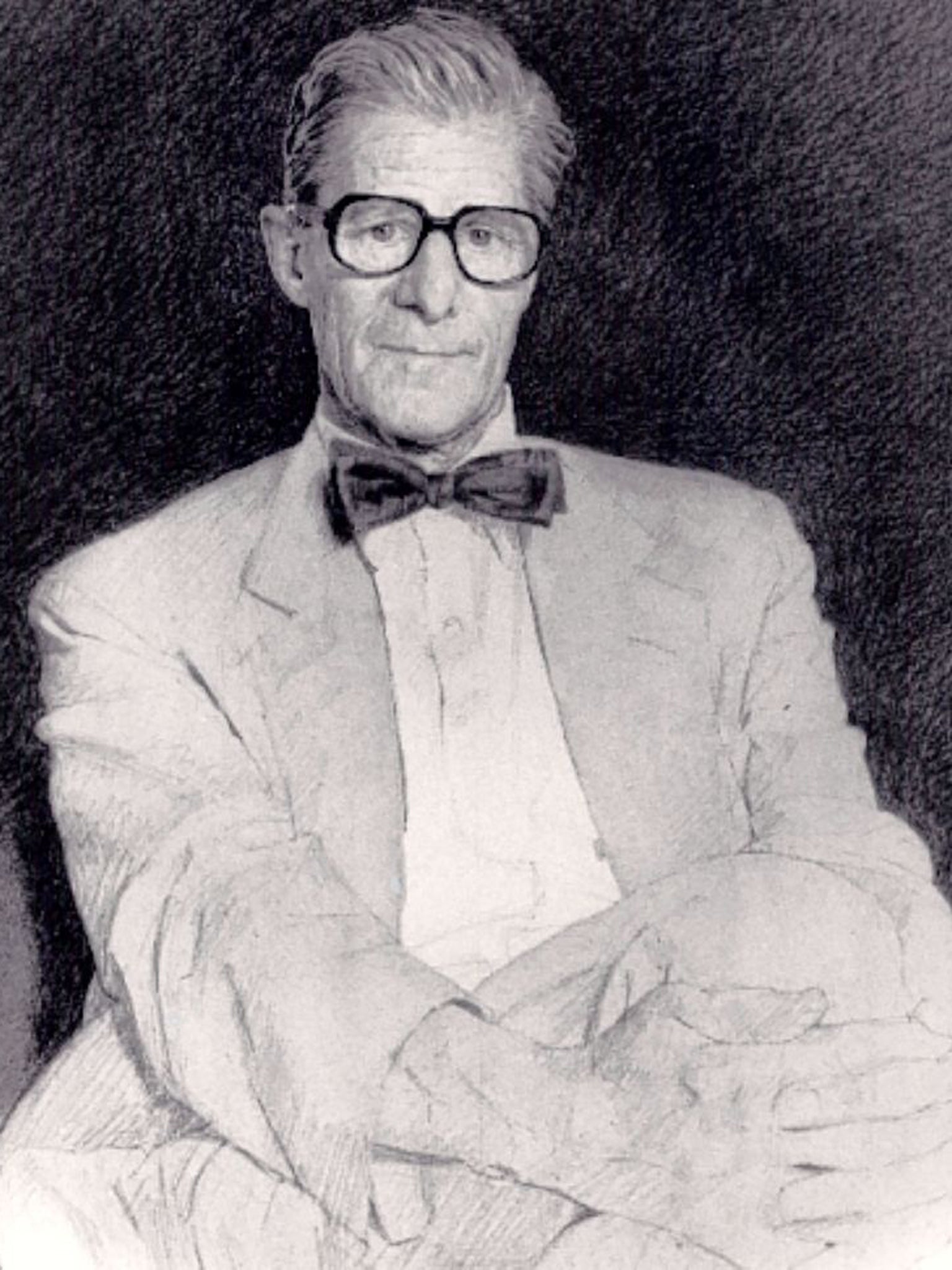

Professor Sir Michael Stoker: Towering figure in cancer research

Michael Stoker was a leading figure in cancer research, both inside and outside the laboratory. Inside it, he pioneered the use of grown cells in the study of cancer; outside it he was hugely influential through his leadership of several major bodies, particularly the Imperial Cancer Research Fund.

Michael George Parke Stoker was born in Taunton in 1918 to parents from Cork. His father was a doctor, and after boarding school Michael went to Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge to study medicine. In a vivid memoir for the Royal Society he describes how the choice of medicine was rather accidental: it was only on exposure to lectures at Cambridge, in physiology and anatomy, from some of the great figures of the day, that he became hooked on biomedical science. He also – "most important of all" – met his future wife Veronica in his final year.

Almost as he started clinical training war broke out, and on qualifying he was sent to India, where he got on to a course in laboratory medicine in Poona, hoping to be able to apply laboratory techniques to tropical diseases; he described it as the most formative 18 months of his career. Again he was taught by outstanding scientists, including Douglas Black, a future president of the Royal College of Physicians, and Bill Hayes, discoverer of bacterial conjugation (essentially bacterial sex – one way that antibiotic resistance can be passed between bacteria). This led to positions at the Military Pathology Lab, where he wrote his first scientific paper, with Douglas Black, and then at the Base Typhus Research Unit. This gave him material for an MD thesis on typhus and got his scientific career underway – leading from bacteria to viruses, from all viruses to those that cause cancer, and then to cancer and the control of cell growth.

Leaving the army medical corps he was reunited with his wife and first son, and they moved to Cambridge University's Department of Pathology. There he began research on viruses, with an interlude studying the bacteria rickettsiae. This was an exciting time, with the prospect of making real progress on common infectious diseases caused by bacteria and viruses, by developing diagnostic tests, vaccines and antibiotics. Among new methods was the electron microscope, which made it possible to see viruses for the first time, and Stoker made use of it along with his colleague Peter Wildy. He learnt to grow cells in culture, essential for work with viruses, and this began a lifelong preoccupation with cell cultures.

In 1956 he was invited to become the first Professor of Virology at Glasgow University, and to head the newly formed Medical Research Council Unit in a new Institute of Virology. He built it into a major centre, recruiting or hosting many key contributors to the field. He made several discoveries and technical advances; perhaps the two most important concerned how cell growth is controlled. With Ian MacPherson he developed BHK cells, the first permanently growing – so-called "immortal" – culture of cells obtained from normal tissue that could be transformed into tumour-like cells by a cancer-causing animal virus.

Before this, the only indefinitely growing cells that could be grown in culture were from cancer cells, and so already had the abnormalities that cancer biologists wanted to study. Stoker also observed that cells could control each others' growth. The normal BHK cells could be "transformed" with a tumour-causing virus. In simple terms this means that they would then divide when they shouldn't. However, if such a "transformed" cell was surrounded by normal BHK cells, it would behave normally — the normal cells could restrain the rogue cell. How this happens is still not known, but it must tell us something about how rogue cells, such as cancer cells, behave in tissues.

In 1968 Stoker became Director of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund's laboratories in Lincoln's Inn Fields, London (now part of Cancer Research UK). He built it into the premier cancer research institute of – at least – the 1970s and '80s, recruiting some remarkable people, such as the Nobel Prize-winner Renato Dulbecco, and fostering work in the emerging field of the molecular biology of cancer. With Dulbecco he also encouraged work on breast cancer. He believed that working in such an institute was a privilege, and that unconditional tenure was not appropriate.

At 60 Stoker returned to Cambridge, and a small lab in the pathology department, and in 1980 he was elected President of Clare Hall, a rather new college for graduates and visiting academics. He and Veronica greatly enjoyed their seven-year term there, presiding over a diverse academic community. He also played an important role in several organisations including the Royal Society, of which he was Foreign Secretary, and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research.

Back in the lab, by careful observation he discovered a new "growth factor", a small protein passed between cells that controls their behaviour. He called it "scatter factor" because it made tight colonies of cells in a Petri dish break up and scatter over the dish. He was involved in work on it for many years.

Stoker occupied two rather different worlds of work, in the laboratory and in the boardroom. His laboratories were small, and he worked at the bench himself when he could, with at most one or two colleagues and assistants, in a truly collaborative spirit. He was proud that all the papers he put his name to – even the one published when he was 85 – included at least some experimental work done personally by him.

This might surprise a young biomedical scientist of today, who sees research group leaders confined to a desk while supervising dozens of people in their laboratory. He was also head or senior board member of major institutions, making strategic decisions that affected many laboratories and many people. He was enormously effective, and much appreciated, in both roles.

Stoker was always busy, but his family was a very important part of his life, particularly his wife Veronica, who died in 2004. To one very junior colleague sharing his lab in the mid-'80s he was approachable, kind and considerate. He showed interest in my work and sometimes gave advice. Very occasionally he would also tell a story. He once recounted how, in about 1962, he was one of the first people to build a Mirror dinghy, having been introduced to sailing at school. He built it in the family home in Glasgow. It was registered as No 39, out of, eventually, over 70,000. I had to concede that this trumped my ownership of No 24,829.

Michael George Parke Stoker, biomedical scientist: born Taunton 4 July 1918; Professor of Virology, Glasgow University 1959–68; Director, Imperial Cancer Research Fund Laboratories 1968–79; President, Clare Hall, Cambridge 1980–87; CBE 1974, Kt 1980; married 1942 Veronica English (died 2004; three sons, two daughters); died Gloucestershire 13 August 2013.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies