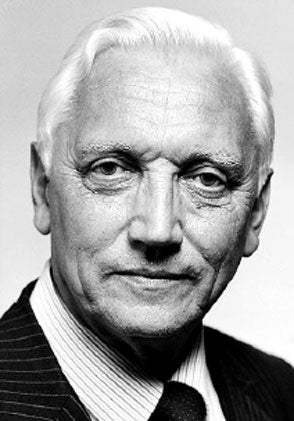

Sir John Hill: Scientist-administrator at the heart of the nuclear establishment

John Hill was the dominant figure in the British nuclear industry through the 1970s. His career coincided with the era when Britain, at great cost, tried and ultimately failed to create its own home-grown nuclear power technology. Lauded and vilified in equal measure, Hill came to embody that period.

Born in 1921, Hill was educated at Richmond Grammar School in Surrey and King's College London, where he read Physics. He spent five war-time years in the RAF, helping develop radar, before studying short-lived radio-nuclei at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, where the atom was first split, and then lecturing briefly on physics at London University.

But in 1950 he joined the great technological enterprise of the day, developing British atomic power. He spent four years at Windscale in Cumbria (now Sellafield), arriving just as the Windscale piles, Britain's first nuclear reactors outside laboratories, began manufacturing plutonium. He helped provide the physics expertise needed to operate them safely and produce the material for British bombs.

In the event, the latter was achieved at the expense of the former. In 1957, as the government rushed to detonate its first H-bombs before an anticipated test-ban treaty came into force, a fire at the piles caused a major accident. Radioactive material was released and blew across Britain – eventally killing, it is now estimated, around 100 people.

But by then, Hill was not directly involved in work on the piles. He had been promoted to take overall responsibility for managing production of uranium fuel, for the first power-generating reactors at Calder Hall and Chapelcross and for the first reprocessing of nuclear waste at Windscale.

He had found his métier as a scientist-administrator, and began a meteoric rise. He joined the main board of the UK Atomic Energy Authority in 1964, and succeeded Lord Penney (father of the British bomb) as chairman just three years later, aged 46. Hill was knighted in 1969. And his control of the British nuclear industry was complete when in 1971 he also became chairman of British Nuclear Fuels, a nominally separate commercial organisation spun off from his old home, the production department of the UKAEA. He held both posts through the 1970s, retiring in 1983.

Hill was a combative and expansionist industrial boss. He told a Commons committee in 1974 that Britain should be building "two or three large nuclear reactors a year". He was frequently at odds with his then political master, the energy secretary Tony Benn, during a protracted period of indecision when both men favoured an industry based on home-grown technology, but could not settle on one design. At one point, they were in charge of building five full-scale prototypes simultaneously.

In the end, facing commercial disaster at Dungeness with his favoured advanced gas-cooled reactor, Hill abandoned them all for the American pressurised-water reactor (PWR) championed by Hill's ultimate successor at the UKAEA, Walter Marshall (later Lord Marshall of Goring).

Benn had begun his time in government as a supporter of nuclear power, but ended it an opponent. He said of the world then dominated by Hill: "In my political life, I have never known such a well-organised scientific, industrial and technical lobby as the nuclear power lobby."

Hill also clashed with Brian Flowers (now Lord Flowers), a nuclear physicist and chairman of the 1976 report on nuclear power by the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution. The Flowers Report is still quoted today for its demand that no more nuclear power stations should be built until the problems of handling waste had been resolved. But Hill was not impressed. "It was a bad and silly report. We should have refuted it more strongly," he said.

Hill's career spanned the growth of environmental opposition to nuclear power, which peaked in two long-running public inquiries, into plans for a giant reprocessing plant at Windscale – dubbed "the world's nuclear dustbin" by Friends of the Earth – and the first British PWR at Sizewell in Suffolk. This opposition was something that the attitudes of the nuclear establishment, with Hill at its heart, did much to encourage.

Hill's style and multiple roles embodied the confusion between the civil and nuclear power programmes, and between commercial and scientific priorities, as well as exemplifying the traditions of high-handedness and secrecy within an industry still largely run by former war-time scientists.

Anthony Sampson, in his The Changing Anatomy of Britain (1982), said Hill became "more like a salesman than a scientist". He opposed a public inquiry over the Windscale reprocessing plant because it might dry up foreign orders. At the same time, fearing a public outcry, he was playing down (some said covering up) a series of leaks of radioactive material at Windscale.

But Hill professed to being confused by the conflict going on around him. He said later, "the gulf between us and the public is extraordinary. They're concerned about dangers that don't worry us at all, while we're concerned about dangers that don't worry them."

Fred Pearce

John McGregor Hill, nuclear physicist: born Chester 21 February 1921; staff, UK Atomic Energy Authority 1950-81, member for production 1964-67, chairman 1967-81; Kt 1969; chairman, British Nuclear Fuels 1971-83; chairman, Amersham International 1975-88; FRS 1981; chairman, Rea Brothers 1987-95; married 1947 Nora Hellett (two sons, one daughter); died Richmond, Surrey 14 January 2008.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies