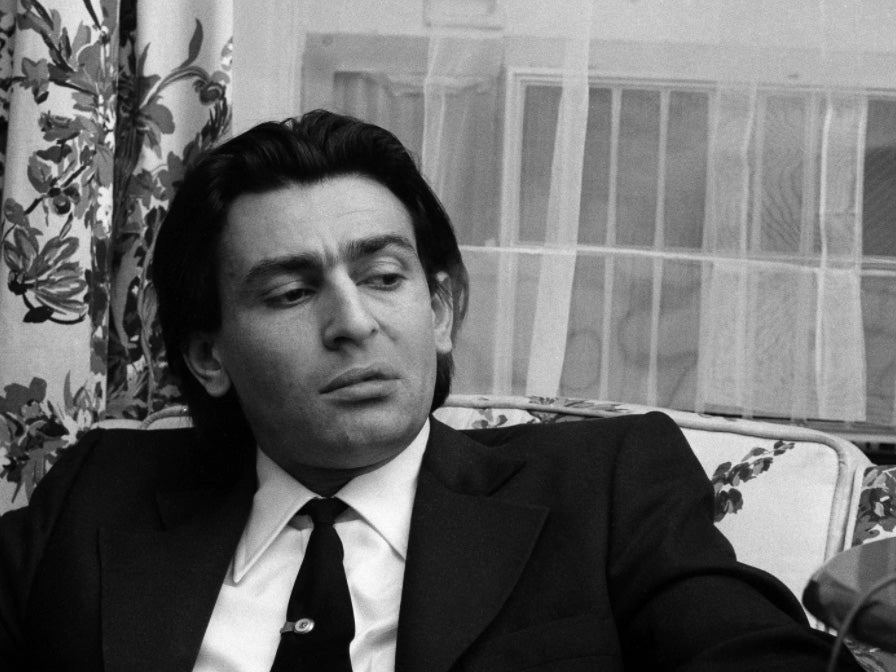

Valery Chalidze: Soviet scientist, dissident and underground publisher forced into US exile

The physicist advocated for free speech and human rights in the 1960s and '70s before his citizenship was revoked for 'acts discrediting a Soviet citizen' – he continued his work in the United States where he taught at Yale University

“I stand on the assumption that the world is normal,” Valery Chalidze said on his first visit to the US in 1972. “I do not expect bad things to happen. I expect to return.”

Chalidze was a physicist and Soviet dissident who helped found a human rights organisation in Moscow with the Nobel Peace Prize winner Andrei Sakharov.

After being forced into exile in the US, Chalidze remained an influential chronicler of Soviet legal affairs and political struggles.

He worked as a theoretical physicist before he was drawn to the growing Soviet dissident movement in the 1960s. He was among several scientists, including Sakharov, Zhores Medvedev and Andrei Tverdokhlebov, who took prominent roles advocating free speech and democratic ideals through dissent and samizdat (the system through which banned literature was disseminated in the USSR).

In Moscow in the late 1960s, Chalidze began to publish the samizdat journal Social Problems, which demanded amnesty for political prisoners and explored legal questions related to civil rights. A self-taught expert on Soviet law, he became adept at outmanoeuvring authorities who kept him under constant surveillance and periodically searched his home.

Chalidze was meticulous in following the letter of Soviet law, while insisting that Soviet officials do the same.

“I was determined to employ only legal methods,” he told the New York Times in 1973. “I would not take any moral positions and would not make any moral claims. I would work without propaganda, without political struggle, without appeals to others – solely through the medium of the law.”

Chalidze lost his job at a physics laboratory and his sister, also a scientist, had to work as a maid. He developed a sardonic sense of humour about life under Soviet rule.

“A pessimist,” he once said, recounting a Soviet-era joke, “is one who says things are absolutely the worst they could be, and an optimist is one who says no, things could be worse.”

His mail was intercepted, and he was often tailed by at least two cars of KGB officers, yet he managed to avoid arrest.

“There were rumours that he could be killed, but it was very difficult to arrest him and put him in prison,” Pavel Litvinov, a fellow dissident who spent time at a prison camp in Siberia, said in an interview. “He was very precise in his formulation of things.”

Whenever Soviet authorities cut off Chalidze’s telephone service, five other families in his apartment building were also inconvenienced.

“I don’t know what is worse,” he told The Washington Post in 1972, “an unpleasant interview with the KGB or bad relations with your neighbours in a communal apartment.”

He became adept at repairing typewriters, which were used to prepare the samizdat publications that were passed from hand to hand. In 1970 Chalidze started the Human Rights Committee with Sakharov and Tverdokhlebov to provide support for groups seeking reform.

“He wrote the first major document about Jewish emigration,” calling for the right of Soviet Jews to travel to Israel, Litvinov said. “He was one of the first who spoke about stopping persecution of homosexuals in the Soviet Union.”

In 1972, Chalidze was granted a visa to travel to the US to speak at human rights forums at Georgetown and Columbia universities.

While he was in New York, two Soviet officials came to his hotel and asked to verify his identity. Chalidze’s passport was seized and his Soviet citizenship was revoked for “acts discrediting a Soviet citizen” and because, as another government official said, he was not “a Soviet citizen in his soul.”

Chalidze continued his activism in exile. He wrote books examining Soviet legal and political life, including To Defend These Rights (1974) and Criminal Russia (1977). With Litvinov, he edited a well-regarded bimonthly publication, A Chronicle of Human Rights in the USSR, which detailed arrests, imprisonments and other acts of Soviet intimidation toward political dissidents.

He helped launch other publishing ventures, including Khronika Press and Chalidze Publications, which issued Russian-language literary classics and translations of works of history and philosophy.

Chalidze also drew attention to Soviet efforts to muzzle Sakharov, a physicist once hailed as “the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb” but whose human rights advocacy embarrassed the Communist regime.

“I do not know how to defend Sakharov – I know only that you will never save anyone by silence,” Chalidze wrote in a 1973 essay in The Times. “I know that many people will cease to believe in mankind’s capacity to combat evil if the world cannot protect Andrei Sakharov.”

Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 but was not allowed to receive the honour in person. He then lived in internal exile until 1985, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev instigated glasnost.

Valery Nikolaevich Chalidze was born in Moscow in the late 1930s. His father, a native of the Soviet republic of Georgia, was killed during the Second World War; Chalidze’s Polish-born mother was an architect and urban planner who helped design the Black Sea city of Sochi.

Chalidze graduated in 1958 from Moscow State University and in 1965 received the equivalent of a doctorate in physics from the State University of Tbilisi in Georgia.

After he lost his job as a physicist because of his political activism, he restored religious icons and altar paintings.

His first marriage, to the former Vera Slonim, the granddaughter of Maxim Litvinov, who was Joseph Stalin’s foreign minister, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife of 37 years, the former Lisa Barnhardt, a lawyer and university professor; a daughter from his first marriage; a sister; and two grandchildren.

Chalidze settled in Vermont in 1983. He taught at Yale University and was a visiting scholar at other colleges and, in his later years, wrote books about human rights, physics and other topics.

In 1985 he received a “genius grant” from America’s MacArthur Foundation, worth in excess of £100,000.

When Chalidze was preparing for his first trip to the US in 1972, a Washington Post reporter asked whether he would be allowed to return to the Soviet Union.

Despite expressing a hope to return, he never saw his homeland again.

Valery Nikolayevich Chalidze, born 25 November 1938, died 3 January 2018

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies