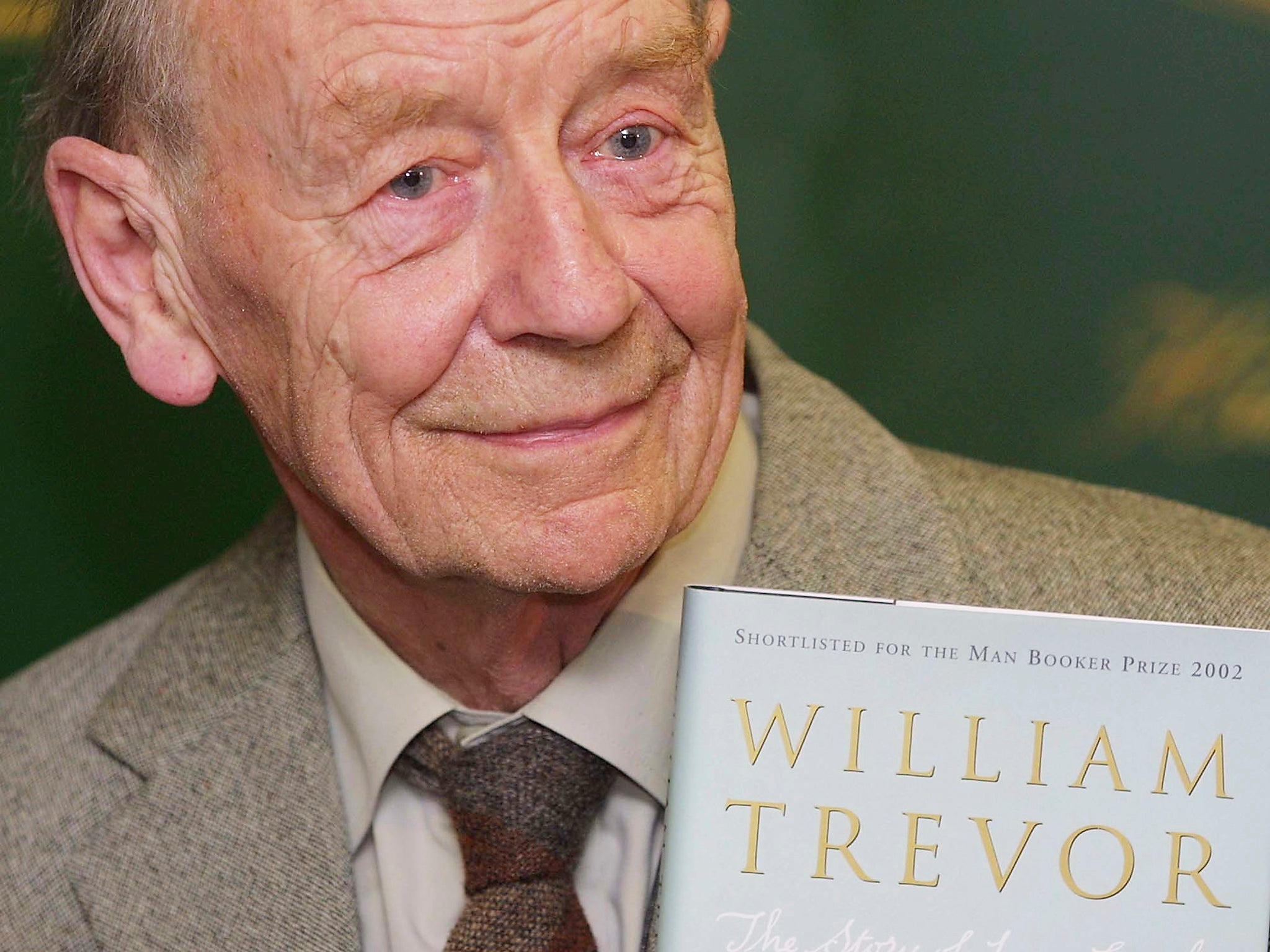

William Trevor obituary: Triple Whitbread Prize-winning Irish novelist, playwright and short story writer

The many novels and short stories of William Trevor, who died this week aged 88, and the adaptations for television and radio which he made of several of them, firmly and subtly stake out a territory he made his own.

From The Old Boys (1964) on, he ruefully chronicled the genteel, the isolated, the disappointed, the eccentric lives of quiet desperation. Trevor’s first half dozen or so books (including his debut, A Standard of Behaviour, published in 1958 and regarded by him as a false start) were set in England and drew on the comic frailties of the English, hopelessly stuck in the grooves of their youth, washed up querulously in boarding-houses, eating out their lonely hearts in Wimbledon. But then increasingly he began to draw on his own small town Irish background, re-creating it with gently melancholy nostalgia, flecked with comedy but also burdened with impotence.

William Trevor Cox (as a writer, he always used the shortened form of his name) was born in Mitchelstown, County Cork, on Empire Day 1928. His father worked for the Bank of Ireland, and throughout Trevor’s childhood the family moved from one small town to another in the south of Ireland, the boy going to 13 different schools. JW Cox was himself a southerner, the family Catholic until late in the 18th century, when (as Trevor put it), “they turned in order to survive the Penal Laws”. His mother was brought up in the North, in County Armagh, a product of “sturdy Ulster Protestantism”. Though Trevor and his brother were loved, and loved their parents in return, the parents were unhappy, and they separated as soon as their sons were off their hands. Years later, Trevor wrote acutely and movingly of all this, unjudging but undeceived in his “Field of Battle”, part of his autobiographical collection Excursions in the Real World (1993).

After his succession of bizarre schools, he had an undistinguished career at Trinity College, Dublin, where he began haplessly in the Medical School, then moved quickly to history. But he came to know and love the city, on long night walks; and he met Jane Ryan, to whom he was married soon after they graduated. It was a supremely happy and long-lasting marriage. Many of his books are dedicated to Jane, others to their sons Patrick and Dominic.

His first job was as a prep-school master in a rapidly declining establishment in County Armagh. When it went bankrupt, he and Jane moved to England, where he found himself teaching art near Rugby, at what he called the second most expensive prep-school in the country. He had, in his spare time, become a skilful wood-carver and sculptor, and indeed had the distinction of winning the Irish section of the "Unknown Political Prisoner" sculpture competition. The final winner was Reg Butler. Trevor was commissioned to make extensive wood-carvings for the church at Braunston, the village where he lived while teaching at the school. Buoyed up a little by these successes, and now thinking of himself as a professional sculptor, he and Jane moved to Somerset, where he sent off work here and there to exhibitions, and eked out a meagre living by teaching art two days a week.

But Trevor’s efforts in the plastic arts didn’t satisfy him (he resented his increasing tendency to “go abstract”), nor did they bring in much money. By now Jane was pregnant. He had managed to finish, and even find a publisher for, his novel A Standard of Behaviour; but Hutchinson did badly with it. If both sculpture and fiction were unrewarding, what could he do?

In 1959, the year after his failed first novel, he somehow heard that there was an advertising agency in London which welcomed “creative writers”. This was Notley’s, the copy chief of which was Marchant Smith (who “resembled, almost perfectly, an egg placed on top of a much larger egg”). The man who notoriously made Notley’s into “a nest of singing birds”, variously employing the poets Peter Porter, Peter Redgrove, Gavin Stewart, Edward Lucie-Smith, and Edwin Brock. Marchant Smith took Trevor on, and early in 1960 Trevor reported for duty.

For some time he had nothing to do. Then he had too much to do. As a copywriter, Trevor found himself wanting. But meanwhile he began another novel, much of which he wrote in office time, on office paper. This was The Old Boys. He also wrote a few short stories, some of which were published by the London Magazine and by another literary journal of the period, Transatlantic Review, run by an enlightened young American millionaire. These stories caught the attention of James Michie, editorial director of the Bodley Head, who – either ignoring, or not having noticed, the dismal fate of A Standard of Behaviour – wrote to enquire whether Trevor had a first novel to offer.

Publishers ought to take notice of Michie’s tactics, once he had accepted The Old Boys. Many publishers flood literary editors, book-sellers, the literary trade in general, with a profusion of ecstatic stuff about the works of genius about to appear. This debases the currency: the encomia cancel out. But Michie didn’t do this. If he saw something was very good, one took notice, because he was notably sincere.

Early in 1964, when I was literary editor of the Listener, Michie sent me a short “personal” letter about a forthcoming Bodley Head novel (Michie I knew only at a distance, as a clever, sharp, sparse poet, and an occasional rather louche visitor on the scene in my undergraduate years at Oxford a decade earlier). He drew my attention to a novel he thought the funniest he had read for many years, and enclosed a proof.

These must have been Michie’s tactics with a number of people, and the ploy succeeded. Not only was I completely dazzled by the sad and hilarious originality of this book (as was the reviewer to whom I sent it), but much weightier people quickly added their superscriptions: Evelyn Waugh called it “uncommonly well-written, gruesome, funny and original”, and all the reviews continued to echo this.

It is indeed a wonderful novel, capable of much re-reading. Reading it myself for the first time, I did what I have very seldom done, and wrote a fan-letter to this unknown William Trevor. Meanwhile, or very soon after, I was raving about it to my friend Peter Porter. He astonished me by saying, “Oh, I know Trevor – we work together at Notley’s. You ought to meet.” Then a short note of pleased acknowledgment arrived from Trevor himself, and we met.

What I remember of our first meeting, or early meetings, is what stays with me still, from more than 30 years of friendship: a wry courtly gentleness, the archaic vowels and word-endings (“orf”, “gawn”, the missing “g” sounds at the ends of verbs and participles – “huntin”’, “lookin”’, which marked him as Protestant ascendancy; but, even more, the amused alertness to what was said or observed. He would note a curious couple in the corner, and convincingly deduce who they were, and why they were there. He would take in, with the subtlest of antennae, the voices of others in the restaurant or bar.

That was one of Trevor’s great gifts – observer, overhearer. He listened. In the interviews with journalists which he increasingly gave as his fame grew, he remarked: “Even now, when people say they’re sorry for rambling on so, I’ve found myself replying that listening is part of the job. ‘Please go on,’ I’ve found myself urging.” He had the most acute ear of any post-war novelist.

The success of The Old Boys meant that, within a few years, he could go freelance. He and Jane moved from Putney to rural Devon where they had bought an Edwardian house with a large garden. He, was a keen – but not too keenly obtrusive – gardener. He worked regular hours at the writing trade, and became much less fond of party-going and pubs. He liked travelling (often to Italy, and to the Ticino in Switzerland), but even these were workdays rather than holidays. He liked to have what he called “a good morning’s work" – which meant something like 8am until a late lunch. His gentle, friendly, relaxed, quizzical manner always had behind a sense of the driven man.

Gradually, the prizes poured in. The Old Boys won the Hawthornden Prize (slipped to him under the table, so Trevor said, by Lord David Cecil); he went on to take the Society of Authors travelling fellowship in 1971, with which he journeyed to what was then called Persia; in 1976, the triple distinction of the Heinemann fiction award, the Allied Irish Banks prize, and the first of three Whitbread Awards culminating in the overall top award in 1995. He was made a Member of the Irish Academy of Letters, had honorary doctorates from universities (Exeter; Trinity College, Dublin; Queen’s University, Belfast), and in 1977 was made an honorary CBE (it had, apparently, to be honorary because he retained his Irish citizenship, though for so long resident in England).

Trevor’s awareness of his “Irishness” never left him, though he was no sort of partisan. He loathed the violence of Ireland – though he once said in conversation that the most effective move would be for someone to assassinate Ian Paisley. Politics bored him, but passion did not and he recognised the passions on both sides in Ireland. At the same time his imagination moved nimbly among matters that, though violent, had nothing to do with Ireland. One of his most memorable novels is The Children of Dynmouth (1976), which centres on an adolescent misfit and psychopath in England. His imagination ranged across many different places and people.

Some have said that his greatest gifts are as a short-story writer. Graham Greene, John Fowles, Francis King and John Banville all said so. Others would see him slightly extended beyond this, as the masterly adaptor of his award-winning stories for the television screen and this is certainly the means through which he won his biggest audiences. For myself, I see Trevor as perhaps the most remarkable all-round prose writer of our time, someone who managed effectively to use all the literary means in his brilliant range.

William Trevor Cox; born Mitchelstown, County Cork 24 May 1928; died Devon, 20 November 2016

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies