Lord Gavron of Highgate: Printing tycoon with keen sense of social justice whose support for Labour was rewarded with a peerage

He was outraged by the exorbitant salaries captains of industry paid themselves

In decline by 1955, the printing industry reached its nadir at Wapping in 1986. Bob Gavron's lifelong faith in the printed word saw him reverse the trend and make a fortune where others failed. Starting as a trainee with Caps Ltd, advertising typesetters in Soho, he realised that the future lay in manufacturing and not originating print.

He startled competitors and unions alike by inviting clients to do their own design and setting, with such success that he was able to dispense with the Caps compositors. In 1964 he borrowed £5,000 and bought an ailing printing firm, renaming it "St Ives" after the town near Huntingdon where it was based.

Concentrating on high-volume periodicals, he made sure the quality of printing came first, along with punctual delivery. With this formula he was able to expand. Other printers were going under, often bought for the value of their lead type. Gavron, who had a shrewd eye for the value of location and property, could buy a business and make it work. He also moved into printing for the City, where new issues created a demand for instant and accurate documents. Finally, he took over the long-established firm of Richard Clay & Co of Bungay, already market-leaders in book-printing, which became the flagship of the St Ives Group.

He came to the trade almost by accident. He was born in Hampstead Garden Suburb, his father a patent lawyer. He went to Leighton Park, the liberal Quaker school near Reading, and then to St Peter's College, Oxford. He played cricket, tennis and rugby, which he always enjoyed in later life. Then and later, he read insatiably; even a short journey was spoiled without a book. He early acquired a passion for George Orwell, increased when he met TR Fyvel, literary editor of Tribune and one of the founders of Encounter. Gavron was reading for the Bar without much enthusiasm, and Fyvel turned him towards publishing.

He fell in love with Fyvel's daughter Hannah, and it was to have means to marry her that he took his first job. They had two sons, and she embarked on the thesis later published as The Captive Wife, examining the role of the mother in an industrialised society. It has become a classic on the subject, reprinted in 1983.

Gavron, who shared her views and supported her work, was heartbroken when she committed suicide in 1965. He threw himself into work, which prospered. He expected others to work hard, too, and he was generous to those who did. He had a natural gift for seeing talent and gave managers free rein. He was regularly seen on the factory floor, where he was regarded with awe. At a time when confrontation was rife, union leaders found him a hard but fair negotiator who would not give in to threats.

One of his closest friends in the trade was Paul Hamlyn, and when Hamlyn sold the firm that bore his name and founded Octopus in 1975, he invited Gavron to join the board. Hamlyn's Midas touch struck a chord with him and he became a trustee of the Hamlyn Foundation, his own taste for philanthropy branching out. He always inclined to the left, but his independent mind prevented him from committing to the Labour Party, although he joined the Institute of Public Policy Research in 1991, becoming its treasurer in 1994. He married again in 1967, to Nicky Coates, who was more politically engaged than he, and their north London house was always filled with Labour people.

In 1985 Gavron, seeing what Hamlyn had achieved by flotation, decided to do the same for St Ives. It was over-subscribed, and those who had worked hard and were rewarded with shares became rich, and he himself a multi-millionaire.

He remained chairman, but without day-to-day responsibility had time for other things. In 1983 he bought Carcanet Press, the leading poetry publisher. Three years later he became chairman of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation and a trustee of the Open College of the Arts, of which he was later chairman. He helped also Carmen Callil's buy-back of Virago, the firm she founded.

His deepest interest was in the Folio Society, the book club specialising in well-designed and illustrated reprints of classic texts. Founded by Charles Ede in 1947, it maintained an enviable record of quality. He decided to see whether more capital and a more entrepreneurial approach could expand its success. He moved it to a renovated building between Holborn and Red Lion Square, which became his office. His sense of what the market could be saw membership rise from 20,000 to 150,000.

He was chairman and director of the National Gallery's commercial arm, chairman of the Guardian Media Group and a governor of the London School of Economics. He was also a director of the Royal Opera House, a trustee of the National Gallery, Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Art, the Royal Society of Literature and the Poetry Society. It was the Royal Opera House, where he had a much-frequented box, that gave him most pleasure; he had a particular passion for ballet.

His generous support to Labour was rewarded with a life peerage in 1999, and after the MCC it was his favourite club. It was also a platform for his views, especially on social justice. He was outraged by the exorbitant salaries captains of industry paid themselves, exclaiming in 2012, "Have they suddenly become 50 times more intelligent or 50 times more effective?" No, he replied, it is because they can help themselves. Home truths like these came easily to him.

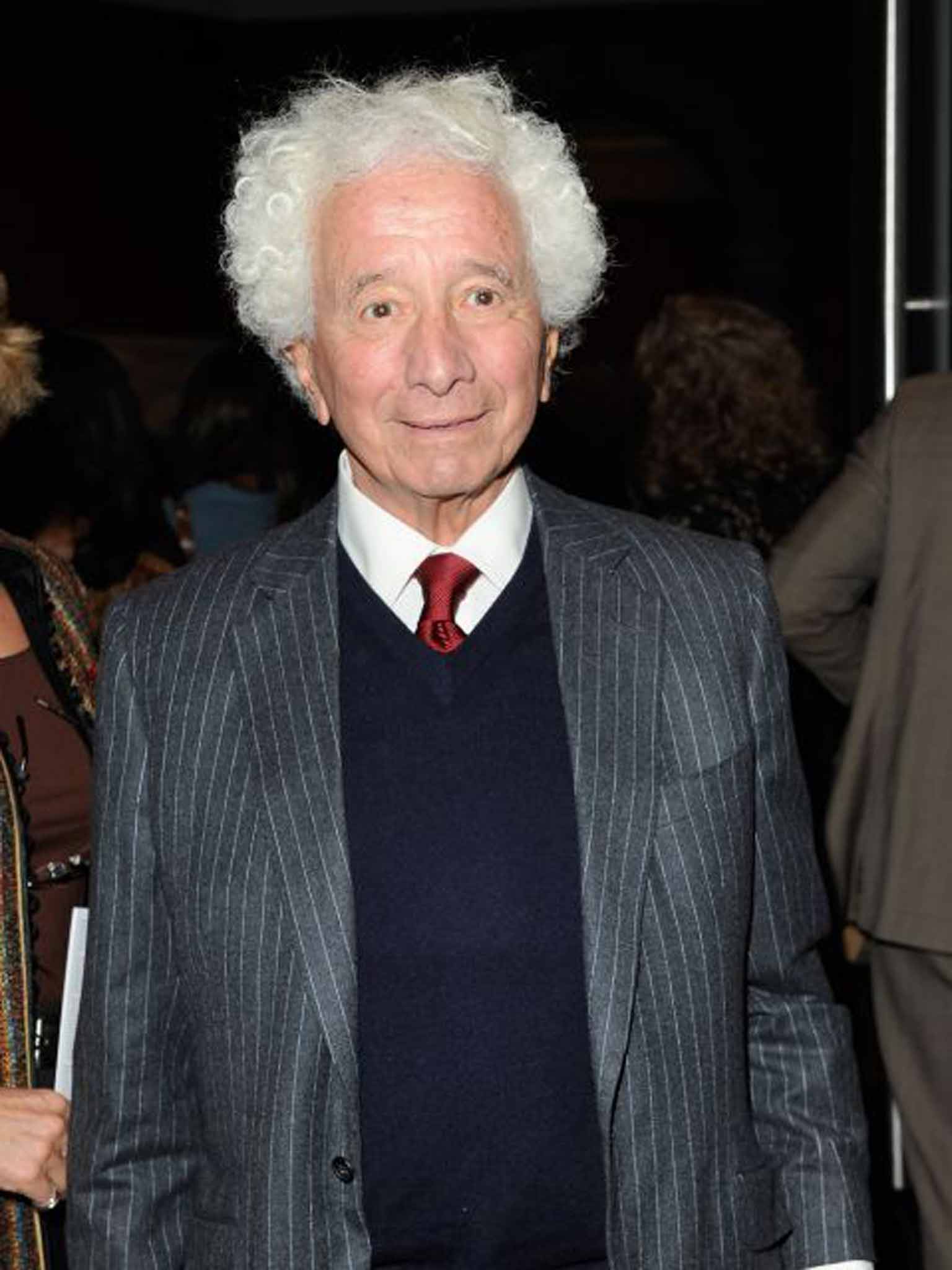

So did his sense of humour. No cause was too serious, no theme too grave to be lightened with shafts of wit. Groucho Marx could have envied his wisecracks. People said he looked like Harpo, but his elegant curly mane of hair was all his own. Nose, eyebrows and mouth were never still, all part of his electric vitality.

In 1989 he married Kate Gardiner, who shared his interest in publishing (they first met to discuss a complete edition of George Orwell) and in social improvement. As Gavron grew older, surviving a heart operation and cancer, they travelled between Provence and Barbados. He died quickly of a heart attack after two sets of tennis doubles.

Robert Gavron, businessman and philanthropist: born London 13 September 1930; CBE 1990, cr. life peer 1999; married 1955 Hannah Fyvel (died 1965; one son, and one son deceased), 1967 Nicolette Coates (divorced 1987; two daughters), 1989 Kate Gardiner; died London 7 February 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies