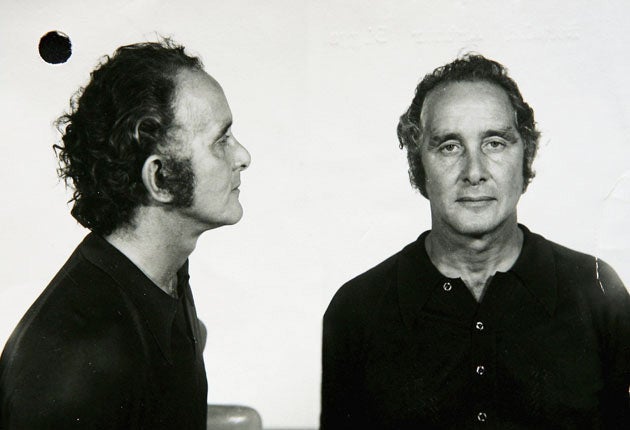

Ronnie Biggs Obituary: From teaboy to Great Train Robber, the charismatic life and death of one of Britain's most notorious criminals

His relationship with a retired train driver led to his inclusion in the team that committed “the crime of the century”

Ronnie Biggs, more than any other criminal of his generation, learnt the hard way just how fine the line between success and failure could be.

When he was no more than a jobbing petty thief among south London’s criminal fraternity, his relationship with a retired train driver led to his inclusion in the team that committed “the crime of the century”. On 8 August 1963, in what became known as the Great Train Robbery, the gang stopped a Post Office train travelling from Glasgow, and stole mailbags containing used bank notes to the value of £2,631,684 on their way to London for pulping.

Ronnie Biggs: The Great Train Robber Dies Aged 84

Biggs’ lowly status as the “tea boy” in a tried and tested robbery team comprising some of the most notable criminal “faces” of their generation, and his subsequent escape, took him around the world and ultimately turned him into a folk hero, while he teased the British legal system to distraction for over 40 years.

Biggs was born in Lambeth in 1929, the youngest of four surviving children of a bus driver father who was a strict disciplinarian. His childhood was little different from any other south Londoner born into the Depression. Biggs was, however, one of a whole generation of future London villainy evacuated from the capital during the Second World War, and by this time petty theft and shoplifting had become normal pastimes for him, which during his time in the West Country served to supplement his meagre diet.

He returned to London in 1942, his mother died a year later and in 1945 he appeared in court for stealing pencils from a shop; two further court appearances quickly followed. In 1947 Biggs joined the RAF and two years later was given a dishonourable discharge following a six-month sentence for breaking and entering.

Shortly after his release he found himself in Lewes prison for stealing a car, and it was here that he met the remarkable Bruce Reynolds. The smart, ambitious and imaginative Reynolds was to forge a career that was the very antithesis of Biggs’ inept ducking and diving. Yet at an early age both men shared a romantic view of the world, encompassing a mutual love of jazz and literature that was to endure for the rest of their lives.

Unlike so many wives of villains, Biggs’s wife Charmian was no bit-part player in the curious drama of his life. They met in 1958 and after a brief courtship eloped to avoid the wrath of Charmian’s headmaster father. The elopement was funded by Charmian’s theft of £200 from her place of work, and when the money had run out the future Mrs Biggs served as a look-out while Ronnie and an associate went thieving. The inevitable failure followed, and Charmian received a sentence of two years’ probation, while her husband-to-be got a custodial sentence of two and a half years.

They were married in 1960; Biggs established himself as a self-employed carpenter and their son Nicholas was born the same year. The family prospered, but in 1963 the birth of a second son, Christopher, found Biggs with a cash-flow problem that he sought to resolve by way of a loan from his old friend Reynolds.

By now a successful thief with a taste for the better things in life, Reynolds declined to loan Biggs the money, but offered him the chance to join in on an unspecified “big job”. The carrot was not a £400 loan but a £40,000 share of the loot. Biggs did not hesitate for long before accepting Reynolds’ offer, but the precondition of Biggs’ involvement required him to recruit a train driver. A disillusioned train driver working past retirement age who had contacted Biggs to carry out some home improvements sprang to mind, and was subsequently recruited.

This was a highly professional team gleaned from two sets of successful robbers who already had considerable experience of both plundering the railways and of high-profile project crime, and the initial response of the robbery team to the recruitment of the incompetent amateur Ronnie Biggs was hostile. But eventually the wisdom that Biggs’ involvement was the price of getting a train driver on their team prevailed.

His task was to act as the train driver’s minder, and to make himself useful generally. However, when the night train from Glasgow to Euston was robbed on 8 August (Biggs’ 34th birthday), Biggs’ train driver proved unfamiliar with diesel technology, and the coshed driver of the mail train, Jack Mills, was forced to move the train according to the robbers’ instructions.

The robbery had been mooted for years among the professional criminal community, but the prize by far exceeded any expectations. The loot amounted to more than £2.5m, and Biggs’s share was £147,000.

However, the robbers had left a wealth of forensic evidence at their base, Leatherslade Farm, near Oakley, in Buckinghamshire, including Biggs’ fingerprints on a ketchup bottle and a Monopoly set, and the team found themselves hunted down within a month. Soon after Biggs had placed his share of the loot with some well-paid minders, he was arrested.

Thirteen gang members were rounded up, and eight of them, including Biggs, were charged with armed robbery. Branded by Mr Justice Davies, the judge who presided over his trial and sentenced him on 15 April 1964, as a “specious and facile liar”, Biggs was sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment, which proved to be the going rate at the first wave of Great Train Robbery trials.

Like many famous escapers, Ronnie Biggs displayed a certain competence as a prisoner that was not apparent during his career as an active criminal. On 8 July the following year, he escaped from Wandsworth prison, via a rope ladder and a strategically placed furniture van, with the necessary funds provided by Charmian.

The story that followed is one of the most peculiar stories to emerge from the sullied ranks of British criminality, mixing farce with tragedy in a manner that would be rejected by any publishing house or film company as being far-fetched. A £40,000 package deal, including passports, transportation abroad and plastic surgery was quickly negotiated, and Biggs found himself in Australia – having travelled via London, Bognor, Antwerp and Paris – with a brand new identity. He was soon joined by Charmian and the two boys and, as the money evaporated, the Biggs family settled in Adelaide, where Charmian gave birth to a third son.

Ronnie returned to his trade as a carpenter before fear of imminent detection by Interpol led to a move to Melbourne. After three years in Australia the Biggs family was tracked down and Charmian was arrested, but not before she had arranged for Ronnie’s escape. Ronnie moved between safe houses before Charmian, having sold her story to the newspapers, funded his fateful trip to Rio.

Britain was awash with rumours of his whereabouts and Biggs was being touted by Detective Chief Superintendent Tommy Butler as one of the ringleaders of the gang. Although he missed his family, Rio suited Biggs; he worked as a jobbing handyman, enjoyed the sunshine, explored the nightlife and discovered dope-smoking. Then, in 1971, Biggs received a letter from Charmian in Australia informing him that their eldest son Nick, aged 10, had been killed in a car crash. Biggs was devastated but, despite the temptation to risk a return to Australia for the funeral, plunged himself into his new life. However, being unable to be with his family gradually weakened his resolve, and by early 1974 he was ready to give himself up.

Biggs realised that with the introduction of parole to the British criminal justice system, had he not escaped from Wandsworth he would now be seeing some light at the end of the tunnel. With surrender in mind, a £35,000 interview deal was set up with the Daily Express. However, Superintendent Jack Slipper of the Flying Squad was tipped off by the newspaper, and arrested Biggs in Rio. Unfortunately for Slipper, who was a veteran of the original Train Robbery investigation squad, one of Biggs’ Brazilian girlfriends, Raimunda, was pregnant and Biggs was the father, a fact that made any attempt to extradite him illegal.

From then on Biggs was in the spotlight. Charmian, who was making a new life for herself in Australia having set up a trust fund with the proceeds of a publishing deal with The Sun, visited Rio and left accepting defeat and divorce – for her husband to leave Brazil would mean that Wandsworth would be the next stop.

Biggs was formally prohibited from working as a condition of his staying in Brazil. After Raimunda gave birth to a boy, Michael, he struggled to support his new family; Raimunda, however, found fame in Europe as a stripper. Biggs sold interviews to the world’s media, published two autobiographies and in 1978 sang with the Sex Pistols on “No One is Innocent” (he claimed to have received no royalties despite the record’s success).

In 1981 Biggs narrowly avoided kidnap by a group of former Scots Guards intent on bringing in Britain’s most wanted man. Two years later the same kidnap team succeeded in getting him as far as Barbados before the Barbadian authorities intervened and Biggs was returned to his sanctuary in Brazil.

His son Michael became a pop singer and Ronnie became a tourist attraction, with his own line in Ronnie Biggs T-shirts, and the $50 “Biggs Experience”, featuring hospitality in the garrulous robber’s home and a chat about the train robbery. He made a small sum of money from a disastrous film, Prisoner of Rio (1988), based very loosely on his story, produced a guidebook to Rio and in later years advertised a hair restorer.

After 29 years he renewed his friendship with Bruce Reynolds, and a year later, in 1993, Jack Slipper, with whom Biggs had engaged in numerous satellite encounters, visited Rio for a reunion to mark the 30th anniversary of the robbery. In 1997 the Brazilian Supreme Court rejected the UK’s request to extradite Biggs, and during the late 1990s he suffered a series of strokes, including one shortly after his 70th birthday, which was marked by another visit by Reynolds and other assorted underworld “faces”.

Declining health, and a desire to spend his remaining days in his homeland, led to his surprise return to the UK in May 2001. Inevitably he was arrested, and was incarcerated in Belmarsh prison in London, a top security establishment, where in July 2002 he married Raimunda.

During his time in Belmarsh, Biggs suffered a series of strokes and minor heart attacks and contracted scabies. By 2004, partially paralysed and unable to speak or to walk unaided, he was being fed by a tube through his stomach while receiving 24-hour care. Yet the Home Office remained impervious to appeals from Michael Biggs, and from his legal team. In August 2004 his lawyers challenged the refusal to transfer Biggs to a more benign establishment, or to release him, as a violation of Prison Service orders and the Human Rights Act. Biggs’s health then worsened, and in 2006 he was moved from Belmarsh to Norwich prison on “compassionate grounds”.

In December 2007 Biggs issued a further appeal for his release: “I am an old man and often wonder if I truly deserve the extent of my punishment. I have accepted it and only want freedom to die with my family and not in jail.”

Early in 2009 Biggs fell ill with pneumonia, prompting fresh calls for his release on compassionate grounds. However, despite a parole board recommendation that he be released, the Justice Secretary Jack Straw refused on the grounds that the 79-year-old who could not eat, speak or walk, remained “wholly unrepentant” for his crimes.

In June 2009 Biggs was taken to hospital in Norfolk with a serious chest infection and a fractured hip, but returned to prison in July, only to be readmitted to hospital with severe pneumonia. In August 2009 he was granted his release on compassionate grounds.

Ronnie Biggs was involved in a crime that, with its military precision and preposterous prize, caught the imagination of a nation barely released from postwar austerity. It is ironic that a rank amateur, whose inclusion in the robbery team was opposed by its other members, should have become the most famous of the masked men who one night in August 1963 robbed the Glasgow-to-London train. His celebrity was based on the fact that his exile was perceived by many as a kind of victory.

Indeed, despite the vicious exemplary sentence that was imposed to mark his violation of the Royal Mail, the bereavement and divorce, the endless ludicrous scams and deals, and the cruelty of his prolonged incarceration, the most vivid image of Ronnie Biggs is to be found on the cover of the first version of his autobiography Ronnie Biggs: his own story (1981). He is pictured laughing, arms aloft and triumphant, on a golden beach under a vivid blue Rio sky. And like so many of his compatriots on vacation, he is wearing a replica England football shirt.

Ronald Arthur Biggs, robber and carpenter: born London 8 August 1929; married 1960 Charmian Powell (divorced 1976; two sons, and one son deceased), 2002 Raimunda Rothen (one son); died London 18 December.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies