Sister Rachel Denton: Why I founded a one-nun hermitage

For Sister Rachel Denton, a convent failed to satisfy the need to be alone with God - so she founded a one-nun hermitage

You seek wisdom, my child?

Well don’t bother going to the bearded hermit in his mountain cave. That’s so 3rd century, which was when St Anthony started the Christian hermit tradition by going for some God-and-me time in an abandoned mountainside tomb in the Western Desert.

Today, if you seek wisdom, stay at home and surf the internet. There you will find @hermitrachel (508 followers and counting), tweeting the words of the Benedictine Raphael Vernay: “The hermit is simply a pioneer in the way of the desert…”

She also has a website. And two Facebook pages.

But if you really must be offline about it, go to an end-of-terrace ex-council house in a village half an hour’s drive from Grimsby. There you will find Hermit Rachel, tending her vegetable garden after rising at 6am for worship in the box room, now converted into a tiny white-walled prayer room. She may be wearing the traditional habit, but Sister Rachel Denton, 52, is the embodiment of the growing tradition of internet-era hermitage.

Just as the 14th-century anchoress Julian of Norwich walled herself up in a tiny cell but allowed herself a window, so Sister Rachel has her own “window on the world”: her computer screen. The internet, says this former deputy headteacher, has its “graces”.

The medieval Julian of Norwich received food passed through her window by admirers. The modern Rachel of Lincolnshire can get her daily bread via internet order and supermarket delivery van: no need to leave the hermitage for shopping.

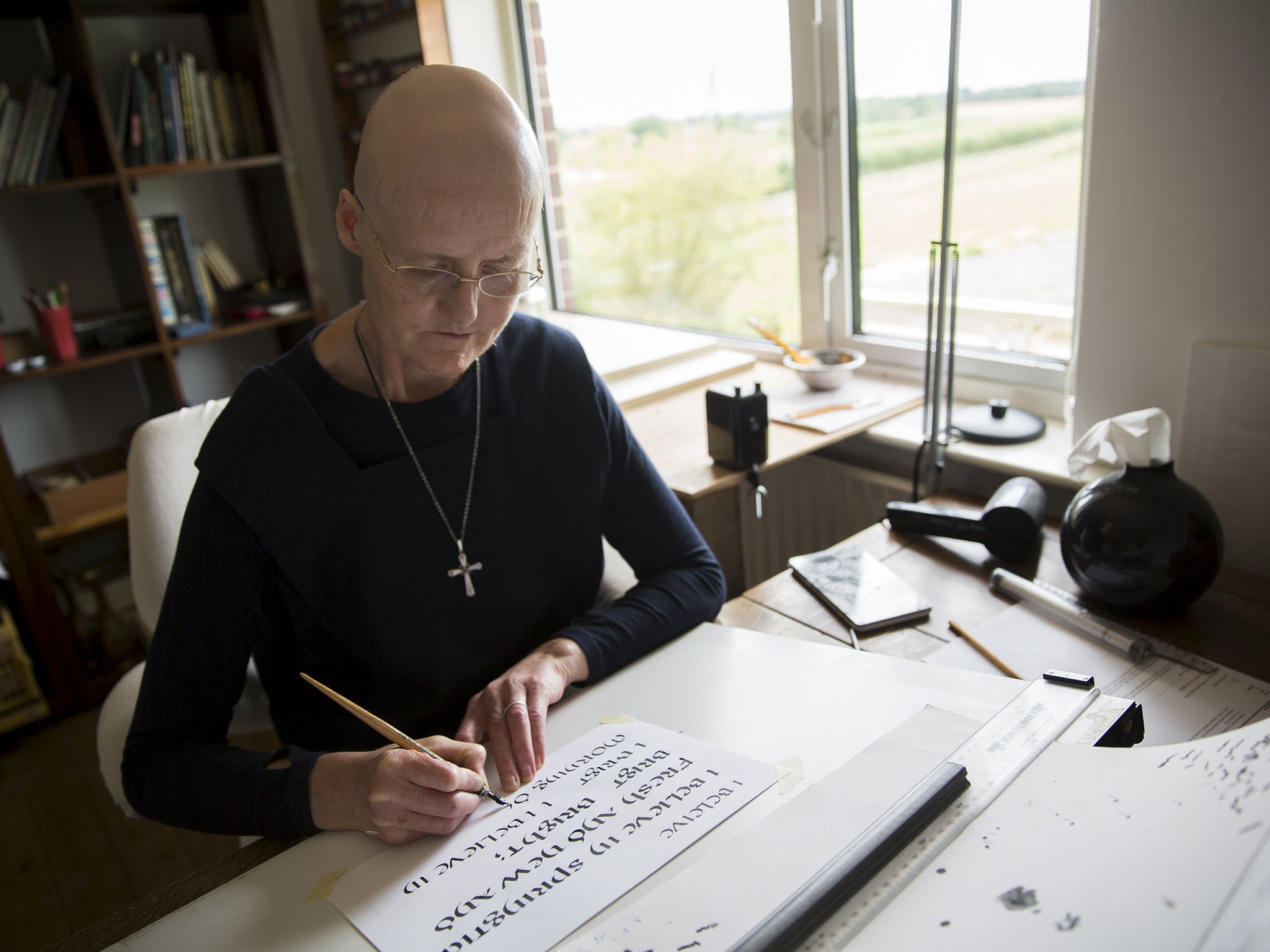

She can also stay “in cell” and earn a living – while paying homage to the monastic tradition of illuminated manuscripts – with her online, one-nun calligraphy business. The private Facebook page provides news of family and friends – “so I can continue the conversation on the two times a year I go to Mass with them”.

Most important of all, the sporadic public Twitter and Facebook posts, plus the website, are “a window into hermitage”, showing that it is still possible to live “in solitude and silence”.

“It probably helps people tap into the hermit within themselves, to realise that hermitage is what they are looking for, even if it means just touching it with their little finger by going for a walk alone.”

About once a month, she gets an enquiry from someone keen to go beyond contemplative walking into full-blown hermitage. And Sister Rachel is far from being the only one using internet technology to revive a tradition that started in a 3rd-century desert cave.

At the American headquarters of Raven’s Bread, the newsletter for the established or aspiring hermit, Karen Fredette, 73, says her and her husband Paul’s website gets 700 hits a day. From 200 subscribers in 1997, Raven’s Bread has increased its circulation to 1,200 today, with 63 UK readers. “We normally acquire 24 new readers each quarter,” adds Ms Fredette. She can also help the novice solitary contact more established hermits for spiritual guidance – over Skype.

It’s all rather different from when Sister Rachel began as a hermit in 2001 and sought the blessing of the Most Rev Malcolm McMahon, then the Catholic Bishop of Nottingham. “He said, ‘We don’t do hermits.’ He didn’t know anything about it – although he did grow to like having a hermit in the diocese: it gave him kudos with the other bishops.”

She may have found her end-of-terrace hermitage via an estate agent’s website, but, she insists, it is closer to the traditions of St Anthony than it looks. Because hermitage, like politics, is the art of the possible.

“The cave and the desert were available to Anthony,” explains Sister Rachel. “But if I put a caravan on the top of Ben Nevis, which is the nearest the UK has to a desert, I would soon be ordered to leave. For the sensible hermit, pragmatism is a virtue.

“People have very romantic ideas, but hermitage is really a celebration of the ordinary.” But for Sister Rachel, the ordinary is best celebrated in contemplative silence – oceans of it, except when The Archers is on. So, yes, she has posted cute Facebook pictures of her chicken Mrs Henny Penny. And there is a radio in her kitchen. “I love The Archers. It keeps me sane.”

She has, she says, wanted something like this since childhood – throughout her “very extrovert job” as a deputy headteacher of the 700-pupil St Bede’s Inter-Church School in Cambridge, and even during her year in a Carmelite convent in the mid-Eighties. “Their tagline was ‘solitude in community’. I loved the solitude, not the community.”

For her, silence means adventure, not loneliness. “For me, that silence is where I can best meet God.”

So in the nicest possible way, she says that when your correspondent finally leaves, “It will be a relief. I can return to solitude like most people return to a family.”

It is a beautiful day. She would like to work in the garden, but she might have to attend to a more irksome task: updating her website.

Cell life: Hermits in history

Anthony the Great (251-356)

Born in Egypt, and widely regarded as the first monk. After 15 years as another hermit’s disciple, he retreated to the desert where he was said to have rebuffed an approach by the Devil.

Julian of Norwich (1342-1423)

The anchoress took her name from St Julian’s Church in Norwich. Her Revelations of Divine Love is the first known written work by a woman.

William ‘Amos’ Wilson (1762-1821)

“The Pennsylvania Hermit” shut himself off from the world after being accused of murder. His cave is now a popular tourist attraction.

James Lucas (1813-1874)

He became a recluse after his mother’s death in 1849 and barricaded himself into his Hertfordshire house. He was the inspiration for Tom Mopes in Charles Dickens’ story Tom Tiddler’s Ground.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies