The key to these ancient riddles may lie in a father’s love for his dead son

Pretty clever, as riddles go

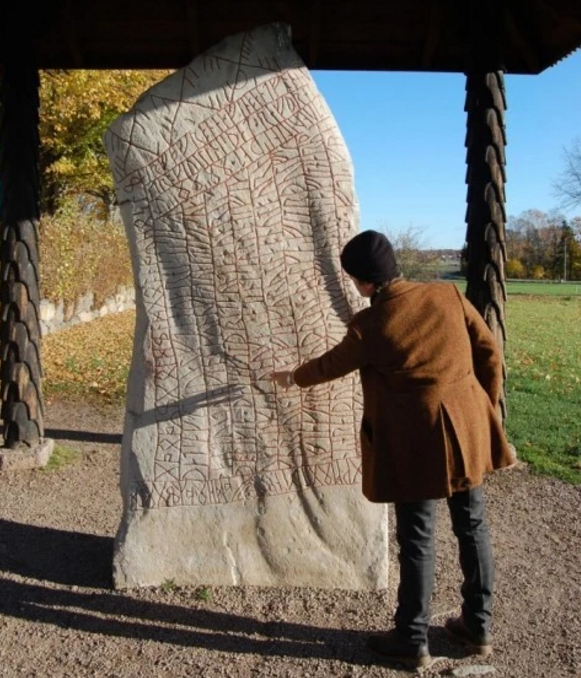

When the Rök runestone was pried from the wall of a small Swedish church more than a century ago, it was heralded as an archaeological marvel. Twice as tall as an adult man and covered in intricately-etched runes, it was the first piece of written literature in Swedish history – and at 760 characters, the longest ever engraved in stone.

The 9th century inscription starts like so many other runestones, with a dedication: "In memory of Vämod stand these runes. And Varinn wrote them, the father, in memory of his dead son."

What follows is line after line of inscrutable riddles, seemingly about ancient figures and sacrifices no one had ever heard of before. The characters of Vämod and Varinn were similarly enigmatic. But the stone was so extraordinary that researchers could only assume it told an extraordinary story. So that's what they went looking for.

A century later, the standard interpretation is a dramatic — if somewhat convoluted — account of heroic feats from history. It includes a Gothic king who famously fought the Romans and long lost fragments of Norse mythology.

"It was a natural thing to think when the researchers began 100 years ago," said Per Holmberg, a linguist at the University of Gothenberg who has studied the runes. The early 20th century was a time of rising nationalism in his country — a climate that lent itself to what Holmberg calls "romantic fantasies" about Swedish origins.

But in trying so hard to find a remarkable origin story for the stone, scholars may have missed its real message, according to Holmberg. In a report in the International Journal of Runic Studies this week, he offers a more modest understanding of the monument.

It's not about ancient battles and conquering kings. It doesn't rewrite history or flatter the state.

Instead, he believes, it's about the power of language and the love of a father for his son, and a testament to how those forces in combination can stand the test of time.

This revised story starts with a simple premise: Rather than assuming that the Rök (which Swedes pronounce "ruhk") is different from other runestones just because it's longer, Holmberg took for granted that it was pretty much the same.

Using "social semiotics" — a linguistic theory that explains how the meaning of language depends on the context where it appears — Holmberg looked at how runes were used on other stones. Runestones are almost always memorials, as this one appears to be, he found. They're also frequently self-referential (apparently the Vikings were pretty into being meta).

Holmberg took those findings back to the Rök stone, which stands beneath a pavilion in a rural corner of the Swedish countryside about three hours southwest of Stockholm. Then he tried another new technique: Rather than read the runestone one face at a time, he followed the inscription in a circular pattern around the sides of the stone.

This solved another puzzle long associated with the stone: It begins by listing, in numerical order, things that it wants the reader to guess ("Second, say who"), but seems to skip items 3 through 11 before arriving at "Twelfth."

But if you read it the way Holmberg did, there are exactly nine phrases after "second," making "twelfth" truly the 12th thing on the list.

Other researchers "have jumped from passage to passage in order to get that heroic story," Holmberg said. "But if you take the reading step by step, it's possible to just take it as ... a sequence of true riddles, not an allusion to a narrative."

That doesn't mean that the riddles don't have larger meaning, though. The ones on the front of the stone seem to refer to the light needed to read them. The ones on the back talk about writing itself.

Take, for example, the line on the front that reads, "Say who of the kinsmen of Ingold was revenged by a woman's sacrifice." Traditional interpreters believe that this references a historical figure who was saved by his wife, though they aren't sure who that person might be.

But Holmberg says that the rune meaning "Ingold" can also be translated as "dawn." In that case, the line could refer to the fact that night, represented by a female goddess in Norse mythology, yields to the arrival of day each morning.

Pretty clever, as riddles go. But why bother? If this is the longest rune inscription ever found in stone, it must have taken its author a very long time to carve. Why didn't Varinn spend that time writing a straightforward narrative about how great Vämod was? Were riddles really the best he could think of to memorialize his slain son?

Holmberg laughed.

"That's a very good question," he said.

But here's his theory: "It's thanks to the technology of writing, Varinn, who erected the stone and inscribed it with runes, is able to keep us reading and keep us answering his riddles. And while we are doing this we are almost forced to commemorate his son."

In other words, the stone is a celebration of how words can make someone immortal. A straightforward history of any sort would have placed Vämod and his whole world squarely in the past. But Varinn's riddles have held researchers in their thrall for more than a century — and, since Holmberg's theory is likely to be challenged, probably for many more years to come.

"In Swedish, we have the phrase 'eternity machine,' " Holmberg mused. It's something akin to da Vinci's and Tesla's dream of perpetual motion — a hypothetical machine that would work indefinitely, driven by a power entirely its own.

"This written text is like an eternity machine," he continued. "It keeps us reading. It keeps us commemorating."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies