No canals on Mars but scientists discover strongest evidence yet planet was once habitable capable of supporting life

Red Planet had at least one large freshwater lake with right sort of chemical make-up to support kind of mineral-eating microbes seen on Earth

Scientists have discovered the strongest evidence to date that Mars was once a habitable planet capable of supporting primitive microbial life-forms at some time in the past.

An international team of researchers has found that about 3.6 billion years ago Mars had at least one large freshwater lake with the right sort of chemical make-up to support the kind of mineral-eating microbes seen on Earth.

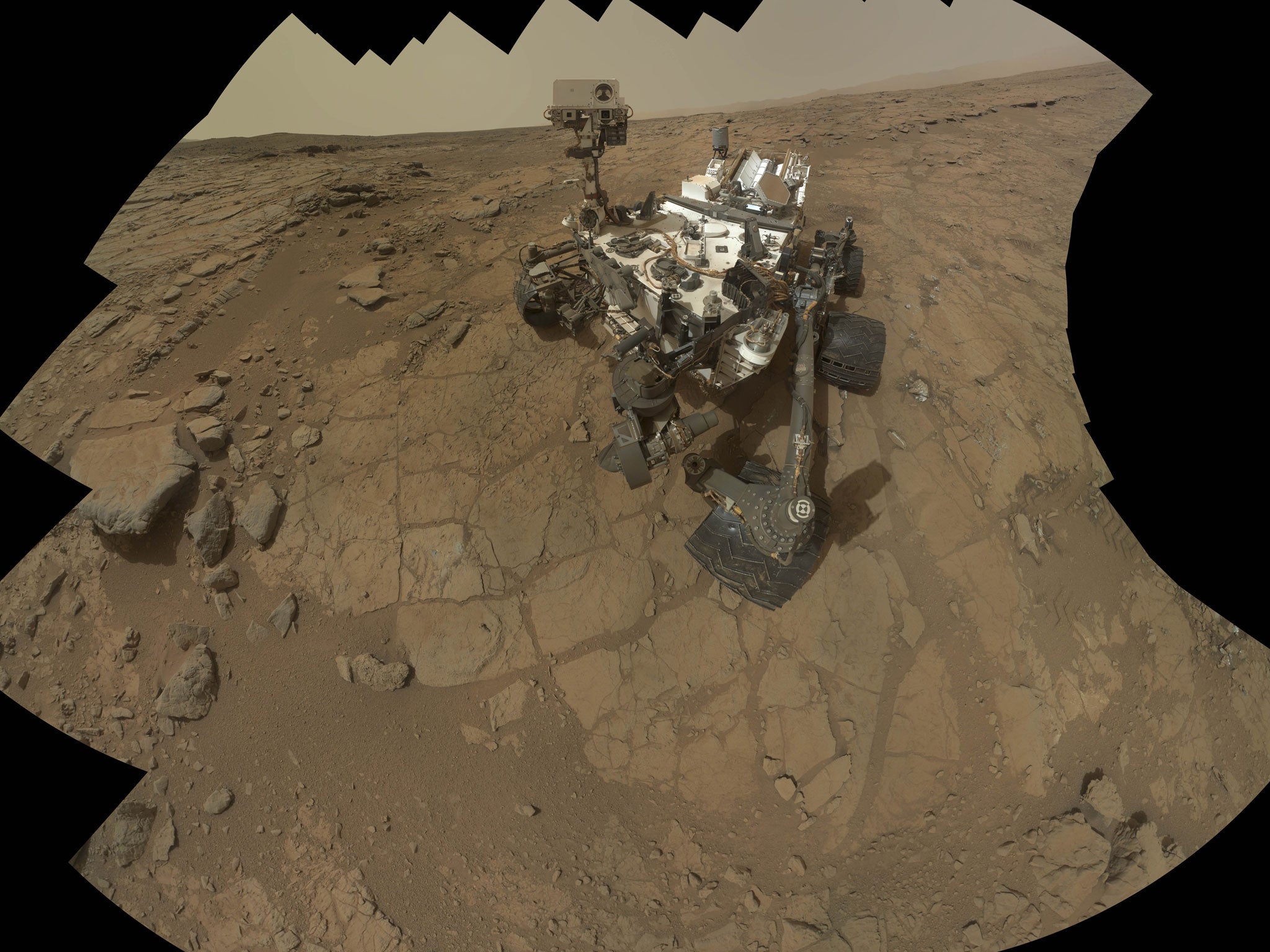

Studies carried out by Nasa’s Curiosity Rover have for the first time revealed the existence of a type of sedimentary rock known as mudstone which is likely to have been created by a large body of standing water that had existed for at least many thousands of years.

Although the scientists emphasised that they have not yet found the smoking gun that proves the past existence of life on Mars, they are jubilant about finding what they believe is solid evidence that the planet was capable of supporting microbial life at some point in the past.

“I think it’s a step change in our understanding of Mars. It’s the strongest evidence yet that Mars could have been habitable for ancient microbial life,” said Professor Sanjeev Gupta of Imperial College London and a member of Nasa’s Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity mission.

“This is dramatic. We have effectively found what was once a standing body of water and although we don’t know how long it was there for, liquid must have been stable on the Martian surface for at least thousands or even millions of years,” Professor Gupta said.

Previous studies indicated that water had once flowed freely on Mars. Satellite images showed the kind of ground erosion that could have been caused by fast-moving water. This was further supported last year when the Curiosity rover found the smoothly-eroded pebbles of a dried-up river bed.

However, scientists believe that fast-flowing water is not conducive for the origin of life and so have been looking for lakes or ponds of permanent standing water that could have provided a more stable, habitable environment for the first Martian life-forms.

Mudstones usually form under calm conditions by the very gradual build up over long period of time of very fine grains of sediment which settle layer by layer on top of each other on the bed of a lake or sea.

The six-wheeled Curiosity rover found the mudstones at a place known as Yellowknife Bay near to its landing site within the Gale Crater, a 150 kilometre-wide impact basin with a mountain at its centre. Nasa sent Curiosity on a detour from its planned exploration of the mountain at the centre of the crater to explore a “thermal anomaly” at Yellowknife Bay.

Curiosity drilled into the rock and tested its composition with instruments designed to analyse the chemical makeup of solids when they are heated and vaporised. The studies, published in the journal Science, revealed the presence of the vital elements of life, namely carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulphur.

The study also found that the relatively neutral acidity of the lake would not have prevented life from forming, that the water was not too salty for life and that it could have existed as a standing body of water long enough for life to form.

It is possible that the mudstone beds extend for hundreds of metres deep under the Martian surface, which would represent tens of millions of years of geological time, the study found.

“We can envisage many combinations of terrestrial microbes that would be suited to form a Martian biosphere founded on chemolithoautotrophy [mineral-eating microbes] at Yellowknife Bay,” the study concluded.

Professor Gupta said: “It is important to note that we have not found signs of ancient life on Mars. What we have found is that Gale Crater was able to sustain a lake on its surface at least once in its ancient past that may have been favourable for microbial life billions of years ago.

“This is a huge positive step for the exploration of Mars. It is exciting to think that billions of years ago, ancient microbial life may have existed in the lake’s calm waters, converting a rich array of elements into energy,” Professor Gupta said.

“The next phase of the mission, where we will be exploring more rocky outcrops on the craters surface, could hold the key to whether life did exist on the red planet,” he added.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies