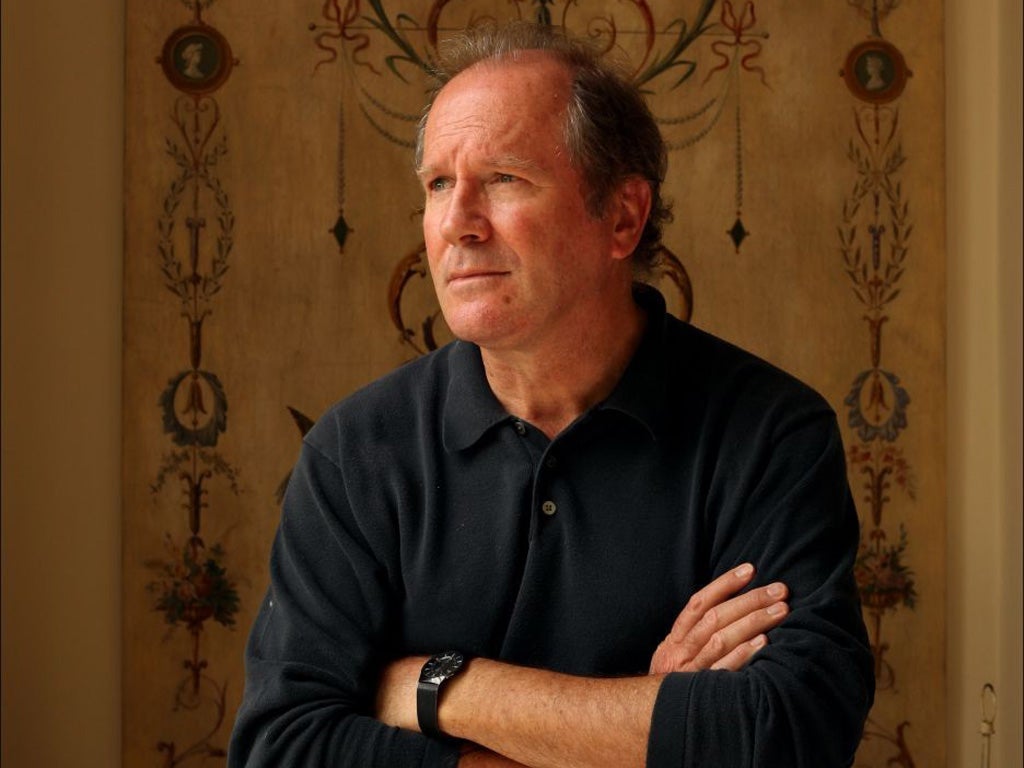

William Boyd: Our man in 007 land

With an invitation to pen the next James Bond novel, this most accomplished of storytellers is poised to win a whole new set of admirers

When it was announced on Wednesday that William Boyd had accepted an invitation by the Ian Fleming estate to write a new James Bond novel, fans of his recent books won't have been much surprised. From Restless in 2006 to the recent Waiting for Sunrise, by way of Ordinary Thunderstorms (2009), Boyd has ploughed a furrow that's perplexed admirers of his earlier "literary" works such as his Whitbread-winning debut, A Good Man in Africa and the Booker-shortlisted An Ice-Cream War.

Boyd's late-middle-period books are thrillers with classic ingredients: spies, femmes fatales, men on the run, men going underground, daring escapes, untrustworthy foreigners, assumed identities and a casual sadism that would have impressed Ian Fleming. In Ordinary Thunderstorms, our hero is pursued by an ex-SAS psychopath called Jonjo Case who likes to flay the skin from his victim's hands and fingers. The protagonist in Waiting for Sunrise, a dim but likeable actor called Lysander discovers an aptitude for torture by forcing Brillo pads into a man's mouth and applying electrodes, plugged into the mains.

Although in each book Boyd's protagonists pause for chin-stroking reflections – on the impossibility of burying the past, the multitude of undocumented missing persons in Britain, the new world order after 1914 – these are not profound works, any more than were Fleming's Bond novels. They're cracking adventure stories – fast, efficient, full of description and short on emotion.

They're still reviewed, however, in the serious, literary-fiction pages of the national press. Although Restless was a "Richard and Judy" selection in 2007, it won the high-profile Costa Award. Literary editors and judges refuse to relinquish their view of Boyd as a superior literary being, a writer of subtlety, poignancy and psychological nuance, as his earlier novels revealed him to be. He is, they admit, a 21st-century avatar of Graham Greene, who blithely interspersed "serious" works (The End of the Affair, A Burnt-Out Case) with action-thriller "entertainments" such as Brighton Rock and Our Man in Havana. The reading public couldn't care tuppence about such matters. They buy Boyd's books in hundreds of thousands because they know him to be the most reliably page-turning of modern English novelists, full of old-fashioned storytelling virtues, of place evocation, pace, drama and sex.

Of the generation nominated "Best of Young British Writers" by Granta in 1983 – the generation of Amis, Barnes, McEwan, Rushdie, Rose Tremain, Pat Barker, A N Wilson, Adam Mars-Jones et al – Boyd's probably the author for whom ordinary readers feel the most fondness. The Queen is known to be a fan, though possibly more because of his Commonwealth background and blue-eyed charm than his prose style. He lives in a handsome Chelsea townhouse, with his wife Susan, editor-at-large at the American Harper's Bazaar magazine (he married her at 23 – they've been married for 37 years, and have no children) and in a converted farmhouse in Bergerac, where he owns a vineyard, Chateau Pecachard. For a chap who turned 60 in March, it seems an enviable life.

The Boyd oeuvre is full of obsessions and recurring themes, the most conspicuous of which is history. His books constantly burrow into the past, tracking through the 20th century, placing characters in the Western Front, the General Strike, the Spanish Civil War, the Blitz, the post-war Manhattan art market. In The New Confessions (1987) a Scottish film-maker called John James Todd fights in the First World War, is a war correspondent in the post-D-Day invasion of France, and winds up embroiled with the McCarthy blacklist of suspected communists. Any Human Heart offers the diaries of Logan Mountstuart, a half-British, half-Uruguayan writer who publishes a best-selling novel in his twenties and spends 80-odd years with writer's block meeting key figures from the literary century: TS Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Evelyn Waugh, Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn. In Restless, he's at it again, as Eva, a Russian émigrée, gives her daughter a memoir of her life as a spy in the Second World War.

Where does Boyd's fascination with people caught up in war come from? His inspiration was close at hand. "People had amazing lives in the 20th century," he told me in 2002. "My wife Susan's father, for instance. He was 19 when he fought at Tobruk, was captured, was a prisoner of war, escaped to Italy, was recaptured by the Germans and shipped to a PoW camp, did slave labour in an ironworks, was shipped to another camp out east. He woke one day to find the Germans gone and the Russians arriving. He commandeered a bicycle and cycled through the ruins of the Third Reich to meet the advancing Americans. Then he went back to Glasgow to become a tea merchant. His life before and after was entirely normal – he got married, had three kids – but in the middle was this extraordinary event. And as that generation grows older and dies, the sons naturally wonder: what can it have been like? And they, the ones who didn't take part, are the generation whose novelists want to write about it."

Identity is another abiding fascination in his work. Characters constantly adopt disguises, change their names (Ruth in Restless discovers her mother isn't Sally Fairchild but Eva Delectorskaya) and become other people. But if you ask William Boyd about his own identity – where he's from – he finds it hard to explain.

He was born in 1952 in Accra, Ghana. His Scottish parents (he a doctor, she a teacher) moved to Africa at the end of the Second World War. He grew up in western Nigeria, and was sent to Gordonstoun, the tough Scottish boarding school attended by Prince Philip and all his sons. (Charles called it "Colditz in kilts".) When Boyd went home for the vacations, it was to an Africa torn apart by strife. The Biafran war raged when he was in his teens. He moved from public-school rules and Scottish gentility to road blocks, strip searches and summary execution. He saw, earlier than most children, the precariousness of life. "It shaped the way I write and it also shaped the way I live," he told the Evening Standard in 2009. "I don't take anything for granted and I advance with due caution. It does mean you seize the day, every day."

After a peripatetic education – he went to university in Nice, Glasgow and Oxford – he lectured in English for three years at St Hilda's College, Oxford, where his good looks reportedly made lady undergraduates swoon.

During this period (1980-83) he wrote his first novel, A Good Man in Africa, set in the fictional African country of Kinjana, and following the politico-sexual entanglements of a conceited but romantic diplomat called Morgan Leafy. Other fish-out-of-water British characters appeared in his follow-up, An Ice-Cream War, set in East Africa in 1914 and starring the upper-middle-class Cobb family. Boyd turned his attention to America in his fourth novel, Stars and Bars, in which Henderson Dores, an art dealer in love with America, tries to acquire a US millionaire's priceless Renoir. Starting out as a typically Briton, Dores ends up clad only in a cardboard box, taken by the locals for just another weirdo.

A Good Man and Stars and Bars were both later filmed to Boyd's own screenplays. He's had a secondary career as a film-maker, both writer and director, adapting the works of favourite writers, such as Evelyn Waugh's Scoop, Joyce Cary's Mister Johnson and Mario Vargas Llosa's Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter. As he told the media last week, he's been involved filmically with three James Bond actors over the years - with Sean Connery in A Good Man in Africa, Pierce Brosnan in Mister Johnson and Daniel Craig in Boyd's first film as director, The Trench. His most successful adaptation was probably that of his own novel Any Human Heart, televised in 2010 in four instalments, to loud acclaim. One light-dazzling moment, in which a boy in a boat sees three incarnations of himself on the riverbank, was especially moving.

As this prodigiously gifted master storyteller contemplates his past, his comfortable present and his James Bond-tastic future, he's entitled to feel a bit dazzled by his own success.

A Life In Brief

Born: 7 March 1952, Accra, Ghana

Family: His father moved to Ghana after the Second World War to run a health clinic, where Boyd and two sisters were born. He has been married to his wife Susan for 37 years.

Education: Attended Gordonstoun school in Scotland before studying at the University of Nice, University of Glasgow and Jesus College, Oxford.

Career: After teaching at Oxford, in 1981 his first novel, A Good Man in Africa, won him the Whitbread First Novel Award. His works include An Ice-Cream War, Brazzaville Beach and Any Human Heart.

He says: "Where do you go when you want to really understand what other people are like? The best place to go is a novel."

They say: "His thrillers occupy the niche that Ian Fleming would fill were he writing today." Corinne Turner, Ian Fleming Publications Ltd.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies