The Big Question: How is Rwanda coping with the aftermath of genocide?

Why are we asking this now?

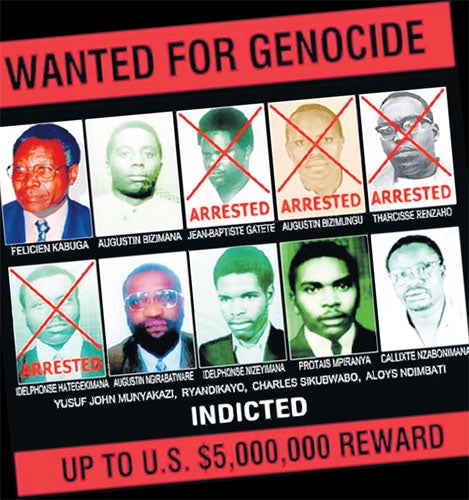

One of the eight fugitives named as ringleaders of the genocide in which around 800,000 people are thought to have died in Rwanda in 1994 has been arrested this week in Uganda.

Idelphonse Nizeyimana was the head of intelligence at Rwanda's elite military training school throughout the 100 days of bloody murder. The violence, which was well organised and methodically executed, was directed against the minority Tutsi people by the majority Hutus, who make up 85 per cent of the population.

The lengthy indictment against Mr Nizeyimana accuses him of drawing up and executing a plan to wipe out the Tutsis and setting up special military units to carry out the slaughter. He is also charged with ordering the establishment of roadblocks across the land at which Tutsis were stopped and slaughtered with machetes. Troops under his command rampaged through the University of Butare to wipe out the Tutsi intelligentsia.

What happened to the other major suspects?

Twenty-three are on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, based in Arusha, Tanzania. The court has so far convicted 34 people and acquitted six. Eight trials have yet to begin. Mr Nizeyimana will appear before the judges soon. The court is due to wind up by the end of this year. The Rwandan government of President Paul Kagame, whose Tutsi-dominated rebel movement brought an end to the genocide, wants Mr Nizeyimana extradited to stand trial in its own courts. They have condemned the UN tribunal for being inefficient, corrupt and not doing enough to protect witnesses. But it has had significant successes, not least when the former Rwandan Prime Minister Jean Kambanda revealed, in his testimony before the court, that the genocide had been openly discussed in cabinet meetings.

What about those who did the actual killing?

Some 120,000 people were arrested after the genocide. They filled Rwanda's prisons to overflowing. Several thousand were tried in Rwanda's criminal courts. But in 2003 President Kagame realised that, at current rates of progress, it could take 100 years to bring them all to trial. It released 20,000 individuals charged with lesser crimes. A year later it released another 30,000 arguing that they had already spent longer in jail than they would have if they were found guilty. To cope it set up gacaca courts. The name came from the small lawn where village elders congregate to solve disputes in traditional community courts.

Like the Truth and Reconciliation process in South Africa?

In some ways. Suspects were taken to the villages which were the scenes of their alleged crimes. There they were confronted directly by their accusers. A key gacaca requirement was that the accused had to ask forgiveness from their victims, or their relatives. But suspects did not have access to lawyers. And the trials were not overseen by qualified judges but by elders respected by local people for their integrity. Some criticised the process because many of the killers seemed more anxious to say what they thought the government wanted to hear – rather than providing the truth about what actually happened in many of the more grisly incidents. And some witnesses were killed by the perpetrators before they could give evidence.

So is it just cosmetic?

Certainly, 15 years on, the genocide continues to loom large over Rwanda. Just a few months ago the Education Minister, Jean d'Arc Mujawamaria, told the Rwandan parliament that research in 32 schools by a committee of MPs had revealed that ethnic hatreds were bubbling up once again.

Despite frequent visits by government officials, preaching against the evils of ethnic division, Hutu students constantly found new ways to harass their fellow pupils – writing slogans on toilet walls, putting rubbish in the beds of genocide survivors, tearing their clothes, destroying their school books, mattresses and kit bags.

But the gacaca system has enabled 12,000 courts to deal with almost a million cases, an outcome which the international pressure group Human Rights Watch adjudged was worthwhile despite its legal shortcomings. The Rwandan President, Paul Kagame, recently told a New Yorker journalist: "Nobody will tell you he is happy with the gacaca," but "gacaca gives us something to build on". The outcome might not be reconciliation but it is co-existence, even if it may remain uneasy for another generation.

What fruits has all this borne?

As it struggles to rebuild itself Rwanda still depends on foreign aid for half its budget. But President Kagame has pioneered new models for using the assistance designed to help recipients become self-reliant. Mr Kagame is unapologetically authoritarian. Critics accuse him of suppressing internal opposition and dissent more ruthlessly than Robert Mugabe does in Zimbabwe. But unlike Mr Mugabe he has brought political, social and economic stability to his country. Today Rwanda is one of the safest and the most orderly countries in Africa. Its GDP has virtually tripled in the last decade. Tourism is booming. Foreign investment is being attracted. New homes, office blocks, hospitals and clinics, shopping centres, hotels, schools, transport depots and roads are being built everywhere. It has an efficient mobile phone and broadband internet service in the cities which is moving rapidly into the countryside.

It has, for Africa, a good health service and a steadily improving education system. Its anti-corruption unit is regarded as a model in the developing world. It is the only government on earth where the majority of MPs are women. And soldiers are almost nowhere to be seen.

What is the outlook?

Western governments, who now provide the bulk of Rwanda's aid, have rallied to help President Kagame. And so they should, since they were indirectly responsible for the plight of the country. It was the former colonial power, Belgium, which drove a wedge between Hutu and Tutsi – who speak the same language and follow the same traditions – by preferring the Tutsis over their fellows. Then the French government supported some of the worst excesses of the Hutu regime. And the United States and others turned a blind eye to the mass slaughter despite being alerted to what was going on by UN peacekeepers. The international community actually withdrew UN troops as the murdering began.

It took more than three decades to teach ethnic division in Rwanda. It may well take just as long to heal it.

Is peace finally taking root in Rwanda?

Yes...

* Rwanda has taken giant steps, through its gacaca courts, to promote co-existence between its peoples.

* Most of those convicted during the genocide have now been released and re-integrated into the community.

* The government is so confident of social stability that it has abolished the death penalty.

No...

* Ethnic divisions between the Hutus and Tutsis are once again bubbling rancorously below the surface.

* Hundreds of thousands of Hutu rebels are still at large across the border in Congo.

* Rwanda's Tutsi-led government has twice invaded its neighbour, saying it wants to wipe out the Hutu forces.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies