Obama's 100 days: Beyond Palestine... the 23-state solution

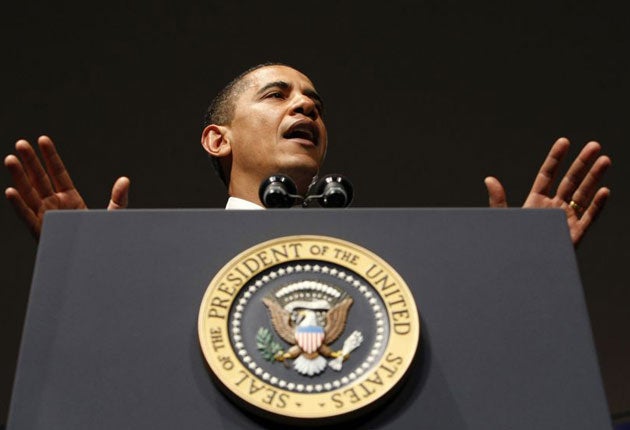

By linking Israel's concerns about a nuclear Iran to his search for a solution to the Palestinian conflict, will Barack Obama finally bring peace to the Middle East? Donald Macintyre reports

Of Barack Obama's two predecessors as a Democratic President, Jimmy Carter, by gripping the issue within months of taking office, achieved more on the Middle East in a single term than Bill Clinton did in two.

The Camp David accord brokered between Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, while an abject failure in relation to the Israel-Palestinian conflict, brought lasting peace between Israel and Egypt.

Mr Clinton, who left serious peace-making in the Middle East to his second term, saw his time in office end with the collapse of talks he hosted, also at Camp David, between Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat in 2000.

Despite the conventional wisdom that it is domestically unsafe for a US President to tackle the Middle East in a first term, Mr Obama appears, so far, to be following Mr Carter's example rather than Mr Clinton's.

If nothing else, the appointment of George Mitchell as a Middle East envoy, the meeting Mr Obama has already held with King Abdullah of Jordan and the invitations he has extended to Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli Prime Minister, and to the Egyptian and Palestinian presidents Hosni Mubarak and Mahmoud Abbas to meet him by early June appear to be evidence that Mr Obama is eager to honour his pre-election promise to seek Middle East peace from "Day One".

It was not obvious that this would happen. However positive President Obama's own interest in a solution in the Middle East, it looked as though the election of Mr Netanyahu – who has not yet committed himself even to the idea of a Palestinian state – had severely narrowed Mr Obama's options. Some Western diplomats thought that the Israeli-Palestinian peace process would have to be "parked" and that the best that could be hoped for would be that the new Israeli leader would pursue, however desultorily, negotiations with the Syrian President, Bashar al-Assad, on a return of the Golan Heights.

So far, the signs are that the White House ambitions are rather grander than that. Indeed, Mr Obama may just be turning to the doctrine of an earlier, Republican, president to define his approach to the issue. For it was Dwight Eisenhower who created the famous doctrine that "if a problem can't be solved, enlarge it."

In a bold speech in Abu Dhabi last November which sought quite astutely to try and influence the approach of an incoming US administration, David Miliband, the British Foreign Secretary, suggested that what was needed was a "23-state solution" – involving the 22 members of the Arab league plus Israel.

In relation to the Israel-Palestine conflict, he made the obvious but seldom stated point that the Palestinians "simply do not have enough on their own to offer the Israelis to clinch a deal". Key to progress, he argued was the Arab peace initiative, which offers recognition of Israel by Arab states – including Syria – in return for a deal with the Palestinians broadly along 1967 borders. It seems that Washington is beginning to buy into this argument. Diplomats report that the administration is making it clear for example that it wants Mr Netanyahu to pursue both the Syrian and the Palestinian tracks.

But beyond all this looms an even larger agenda: the so called "grand bargain" in which Israel stands to gain a swathe of international support, including from Sunni Arabs, for a determined approach to the nuclear threat posed by Iran, in return for progress on an Israeli-Palestinian deal. Some diplomats have talked of an eventual US-European guarantee to Israel and the Arab League states against any Iranian threat, along the lines of Nato's Article 5, (under which Nato is obliged to defend any of its members that come under attack).

Given Mr Netanyahu's stated and overwhelming preoccupation with Iran, his talks with the US President are likely to focus in large part on what he can offer for the assurances he wants on Iran. What's important about this is that Israel-Palestine and Iran become not competing items in the Obama in-tray, but ones that are inextricably connected.

So far, the US appears to be showing a certain steel. The President went out of his way in his speech in Ankara earlier this month – some say despite reservations from State Department officials – to restate his desire for a two-state solution, just as Mr Netanyahu was ostentatiously refusing to commit himself to one as he took office in Israel.

US spokesmen, including Mr Mitchell, have begun to talk openly about the "American interest" that would be served by an Israeli-Palestinian deal. European diplomats judge that Hillary Clinton's expression of irritation during her trip to Ramallah last month at plans for settler-driven house demolitions in East Jerusalem which threaten to undermine any progress towards a two-state solution, should be read as a genuine warning to Israel.

And finally, Mrs Clinton appears even to have altered US policy on a Hamas-Fatah Palestinian unity government last week. She made it clear that to qualify for US support, the government itself – rather than Hamas as a movement – would have to collectively to sign up to conditions like the recognition of Israel and a renunciation of violence.

As US policy evolves, questions remain. Will the US draw up its own blueprint for a deal, as some European diplomats believe it should? Even if it cannot impose a deal, will it at least prevent the kind of settlement expansion in the West Bank and East Jerusalem which continued unabated under George Bush and which now threatens to torpedo the chances of a two-state solution once and for all? And with all the other claims for his attention, is Mr Obama prepared to risk a confrontation with Mr Netanyahu by making the conflict the priority it needs to be?

The signs, at the 100-day mark of Mr Obama's first term, are that a strategic vision is taking shape; realising it would need the combination of tenacity, luck, and courage which has eluded all of Mr Obama's predecessors over the past four decades.

Peace negotiations: The key players

1. Benjamin Netanyahu

Long seen as a hawk, the former prime minister recently returned to power at the head of a right-wing coalition in Israel, prompting pessimism about a peace deal. But his deep aversion to a nuclear Iran may open up negotiations on Palestine.

2. Hosni Mubarak

After 28 years in office, the 80-year-old Egyptian President has visited Israel only once, for Yitzhak Rabin's funeral. But he has little time for Hamas and has long been the prime mover in an uneasy accord with Israel that may not survive his departure.

3. Mahmoud Abbas

Although his influence is thought to be on the wane in Palestine, and he has almost no following in the Gaza Strip, the Fatah leader remains the negotiating partner of choice for Israel and the West. He faces pressure from within his own party as well as Hamas.

4. Bashar Al-Assad

Despite Syria's long mutual antipathy with Israel, the President led his country into indirect peace talks last year, and relations had warmed considerably, but he says Netanyahu's rise is an obstacle to peace. An essential partner in any deal on Palestine nevertheless.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies