The Big Question: What is the extent of European royalty, and does it still have a role?

Why are we asking this now?

Because Holland is seized with rumours that its monarch is about to abdicate. This week Queen Beatrix will celebrate her 71st birthday – which is the age at which her own mother, Queen Juliana, abdicated. The Dutch crown prince Willem-Alexander, who has a day job as an expert in water management, became 42 on Monday, the same age his mother was when she ascended the throne in 1980. Abdication is a well-established tradition among the Dutch royal family.

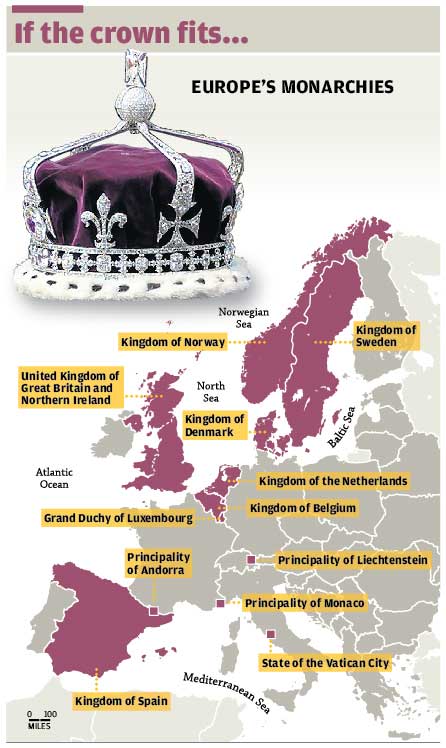

How many monarchies are left in Europe?

Ten, in Belgium, Britain, Denmark, Holland, Norway, Spain and Sweden, with the principalities of Liechtenstein and Monaco and the Grand Duchy Luxembourg included. Technically speaking the Vatican City is also a monarchy. The official definition of a royal family includes any ruling a sovereign country at the Congress of Vienna of 1815, even if the country is now a republic or ceased to exist. There are 21 royal families without a country to reign over.

Do any of them still exercise power?

Not in the sense that monarchies do in Saudi Arabia or Kuwait where royals routinely hold key government jobs. But not all are purely ceremonial like the King of Sweden whose responsibilities don't go much beyond cutting ribbons and waiving to crowds. Some have a potency, if not a power. The royal family in many countries are seen as intangibly important to national identity.

In Holland the royal family is an important talisman of Dutchness at a time when the Netherlands is struggling with its national identity. It is particularly popular with ethnic minorities who like the wife of the heir to the throne, Princess Máxima. She herself is a recent immigrant and she does public works on issues of integration and the inclusion of women. But some European monarchies still have considerable political influence.

Which is the most powerful?

In Holland the Queen chairs the council of state which scrutinises government legislation before it is put to parliament. She also appoints the formateur, the politician whose job it is to form a coalition government after general elections. She holds weekly meetings with the prime minister. Queen Beatrix wields more power than most of Europe's reigning monarchs, especially in international relations; she once threatened to dismiss a cabinet minister if he turned down her request to open a Dutch embassy in Jordan.

In Belgium the King of the Belgians (he is named for his people not their territory) is a constitutional monarch who accedes to the throne, not upon the death of his predecessor, but on taking a constitutional oath. He too has power in the formation of the government. He meets with the prime minister at least once a week, and regularly summons other ministers and opposition leaders to the palace. He has the right, like the British monarch, to advise on government policies.

The Belgian King is above the law. He cannot be prosecuted, arrested or convicted, nor can he be summoned before a civil court or parliament, though he could be brought to book at the International Criminal Court under European law.

Are these monarchies modernising?

Slowly, in both style and law. The Dutch have had bicycling royals for decades. Queen Juliana routinely left behind her gilded palace to drop in, unannounced, on schools and other institutions near her home. During Holland's worst storm in 500 years, dressed in boots and an old coat, Queen Juliana waded through water and deep mud to bring food and clothing to her devastated subjects. But her daughter, Beatrix, has been more formal in her time as Queen.

Several monarchies – including Norway, Belgium, Sweden and Denmark – have changed their old Salic laws of succession to allow their monarchs' daughters to succeed on equal terms with their sons.

Will they survive?

Quite probably. In Holland, for example, a majority of parliamentarians, on paper, want to limit the power of the royal family. But with the monarchy currently boasting a 85 percent approval few politicians want to take the risk of raising the subject with voters.

There seems little appetite for change elsewhere. But royal families know they are vulnerable to the volatility of public opinion, particularly when scandals rear their head. The present popularity of the Dutch royal family stands in contrast to the position in 1976 when it was revealed that the Queen's husband, Prince Bernhard had accepted a $1m bribe from the aircraft manufacturer Lockheed to influence the government's purchase of fighter aircraft. The prince was forced to resign as an admiral, general and as Inspector General of the Armed Forces. But the monarchy survived.

What are those who have been ejected from power doing now?

Some, like the King of Greece, retain in exile their pretensions of royalty. Constantine II, who fled to Rome when a group of Greek colonels toppled the elected government in 1967 was declared deposed and he did not return even after the junta fell in 1974. He and his wife and children, who now live in London, are still invited to functions by reigning royals many of whom are related to him, thanks to the propensity of his forebears for keeping marriages within the European royal family.

Others keep their head down for different reasons. The Liechtenstein dynasty runs a bank which the US Senate's subcommittee on tax havens has described as "an aider and abettor to clients trying to evade taxes, dodge creditors or defy court orders". The son of the former King of Italy has been working as a hedge fund manager in Geneva.

Could these royals ever return?

The hedge fund manager had lawyers write to the Italian government a couple of years ago seeking damages for his years in exile and demanding the return of the Quirinale palace in Rome. The government threatened a counter-suit for damages arising out of the royal family's collusion with Mussolini. King Michael I of Romania, who was forced by the Communists to abdicate in 1947, became a commercial pilot and worked for an aircraft equipment company. After the fall of Communism he declared: "If the people want me to come back, of course, I will come back".

Three years later, when he returned to the country to celebrate Easter, a million people turned out to see him. The new government promptly banned him again. A poll in 2007 showed that only 14 per cent of Romanians were in favour of the restoration of the monarchy. A year on, however, the figure had risen by two per cent.

It will take a long time before the figure rises to the 85 per cent rating of the royal family in Holland. And, no doubt, the Romanian government will do all it can to restrain the notion. But it shows that, for all its failings, the attraction of royalty is far from dead.

Is monarchy on the Continent on the way out?

Yes...

* Three-quarters of European countries, 35 in total, have now waved goodbye to their royal families.

* There are 21 royal families without a country to reign over; the rest have died out.

* Many parliamentarians want further curbs on the powers of constitutional monarchs.

No...

* Royal families are still seen as embodying something important about national identity.

* Royals are changing their behaviour, and their laws, to match the changes among their people.

* The monarchy gets approval ratings as high as 85 per cent among many voters fed up with their politicians.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies