Germany's last Nazi hunter Thomas Walther, interview: 'I was retiring so I decided to do something useful'

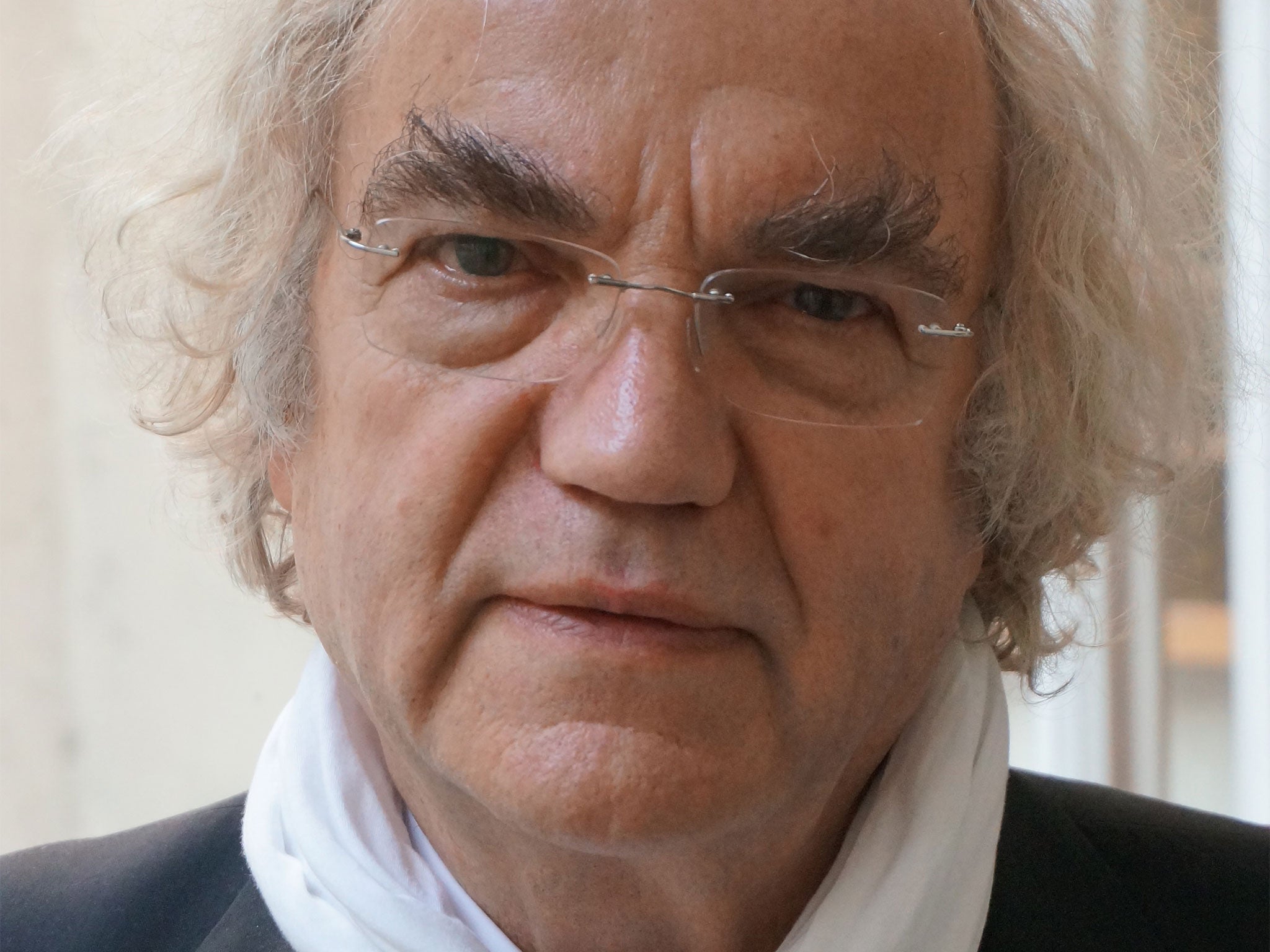

Thomas Walther tells Tony Paterson in Lüneburg that it was only when he retired as a lawyer in 2006 that he realised he had to 'do something useful'

It is a spectacle few Holocaust survivors dreamt they would witness 70 years after the end of the Second World War: in a courtroom in the picture-postcard German town of Lüneburg, a 93-year-old man with thin parchment-like skin hobbles towards his seat near the judge with the help of a rollator. He is so frail that he is supported by two orderlies.

Oskar Groening is one of the last surviving SS guards to have served in the Auschwitz death camp, where more than a million people were systematically murdered in the Holocaust. Today, Groening sits face to face with his now grey-haired and often equally frail surviving victims and their relatives. Several have travelled from America, Canada and the UK to give evidence at what has been called “Germany’s last Auschwitz trial”.

With their testimony, death-camp hell is suddenly and horrifically relived: the excrement-filled cattle trucks in which Jewish prisoners were transported for days, often without food or water, before arriving at Auschwitz: the machine guns, the uniformed SS men screaming orders before marching whole families off to the gas chambers.

For Groening, the confrontation with his former victims is often too overwhelming to bear: “There is no question that I am morally guilty – I beg for forgiveness,” he tells them.

On Thursday, doctors announced that the strain of the proceedings was taking its toll on the former SS man, who is charged with being an accessory in the murder of 300,000 Auschwitz prisoners. His trial has been interrupted to enable him to recover.

Without the efforts of a trained lawyer and former German judge called Thomas Walther, it is unlikely that Groening would ever have been put on trial. Until last year, it was assumed that his case had simply been forgotten by the German judiciary. Mr Walther – who has quietly earned himself a reputation as Germany’s “last Nazi hunter” made sure that proceedings against him were started. In doing so he has reopened a chapter of German justice that most had assumed was closed for good.

Mr Walther is a self-effacing man in his early 70s. His jeans, trainers and the almost-shoulder length hair suggest that he was always something of a rebel. “I am a product of the ‘68 generation,” he told The Independent in the lobby at Lüneburg’s luxury Bergstroem Romantik hotel.

Holocaust Memorial Day 2015: Haunting images of Auschwitz

Show all 20Thomas Walther was only a baby in 1945. He says his father later made him aware of what the Nazis did with the story of how his family had given two Jewish families sanctuary on the so-called Nazi “Kristallnacht” of 11 November 1938. Hundreds of synagogues and Jewish businesses were ransacked in a chilling foretaste of the Holocaust that was to follow. The Walthers helped their Jewish friends escape to Paraguay and Australia: “Fred Biel is the name of one who went to Australia – I still have contact with him today,” Mr Walther said.

But as a law student at Hamburg university in the 1960s, the Holocaust and the way the then West German judiciary dealt with perpetrators was hardly an issue. “We were young socialists and our main interest was reforming the Social Democratic Party from within – the Holocaust was not on our radar,” he admitted.

In 1957, Fritz Bauer, a legendary German-Jewish state prosecutor was tipped off that Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi who organised the transport of Jews to Auschwitz, was hiding in Argentina. Mr Bauer was so doubtful of the Germans’ willingness to extradite Eichmann that he opted to give the information to Israel. Mossad, the Israeli secret service, subsequently tracked down Eichmann, captured him and put him on trial in Jerusalem. He was hanged in 1962.

More than 120,000 investigations of suspected Nazi war criminals were carried out by post-war Germany, but only 560 people were convicted. “When the first Auschwitz trials began in Frankfurt in 1965, the police on duty at the court stopped short of giving the accused a “Heil Hitler” greeting, but they saluted them all the same,” Mr Walther recalled. “The press coverage was minimal,” he added.

Mr Walther admits that like millions of other Germans, he was content to keep the Holocaust under the carpet. “At the time, the Cold War was the big issue, everyone was worried about the Soviet Union,” he said. He spent most of his career as a judge and prosecutor working in the south German provinces. But, in 2006, shortly before he was due to retire, he decided to “do something useful” and accepted the offer of a job at Germany’s central office for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals in Ludwigsburg.

At Ludwigsburg, Mr Walther soon came face to face with the enormity of Nazi crimes. “The judiciary was content to prosecute on a piecemeal basis. The judges demanded eyewitnesses and evidence to get a conviction. The deputy commandant of Auschwitz was only convicted after three pieces of paper were produced showing that he had signed orders to commit mass murder,” he recalls.

Even in 2006 there were suspected Nazi war criminals like the Ravensbrück concentration camp dog handler, Elfriede Rinke, who had escaped conviction. Rinke belonged to a group of guards whose dogs were used to maul prisoners to death. “There was nothing left of these prisoners, their flesh was torn to shreds – but at Ludwigsburg I was told I could not begin to prosecute Rinke because I had no witnesses,” Mr Walther says.

His break came in 2008, just as the Ludwigsburg Nazi prosecution unit was celebrating the 50th anniversary of its founding. Important guests from America were expected to attend the event. At the same time, a former SS guard at the former Nazi extermination camp of Sobibor called John Demjanjuk was in the US and facing the possibility of extradition to Germany. “I pointed out to my superiors that it might be problematic, if we could not mount a case against Demjanjuk,” Mr Walther recalled.

He seized his chance. The Demjanjuk case brought a sea change in the German judiciary’s take on Nazi war criminals. Mr Walther argued that Demjanjuk could face prosecution without the evidence of eyewitnesses, and solely by dint of the fact that he was employed as a guard at a camp where all the inmates were instantly dispatched to the gas chambers on arrival. As such, he maintained Demjanjuk was automatically part of the Nazi mass murder machine.

The judiciary agreed. On the basis of his Sobibor guard's ID card, Demjanjuk was convicted in 2011 by a Munich court of being an accessory to the murder of 27,900 Dutch Jews at Sobibor. He was sentenced to five years imprisonment. “Demjanjuk was just the opening shot,” Walther says. “There should have been many more prosecutions like his. For decades German justice just failed to apply laws about being an accessory to mass murder that were already in place.”

Oskar Groening is the latest former Nazi guard to face charges of being an accessory to mass murder. He may be the last one. Lawyers representing two other surviving Auschwitz guards who have been identified in Germany, claim that their clients are “too frail” to stand trial. “German justice may have finally come for those who survived the Holocaust – but has arrived very, very late,” admits Mr Walther.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies