Mary Dejevsky: Don't knock Boris and Ken – they're making democracy work

To cite London as proof that mayors are a bad idea is to disregard the real changes they have brought

What do the 2012 Olympics and mayoral elections have in common? Here's a clue: it's not London. Other places are voting on mayors, too. The answer is that both are being vilified in a nasty, negative and condescending way by the metropolitan chatterers, who regard them as impediments to the smooth functioning of their gilded lives and just the latest examples of the "dumbing-down" of modern life.

With mayoral elections, the sentiment comes disguised in many ways. It comes as election overload: voting for mayor is one ballot paper too many. It comes as cynicism: it won't make any difference; all power is concentrated in Westminster. It comes as economic concern: mayors, and electing them, cost money at a time when nurses, free school meals, swimming lessons – insert your favourite public service – are being cut, so now is not the time. It comes as a defence of the national culture: elected mayors are American, or Continental; that's not how we do things here.

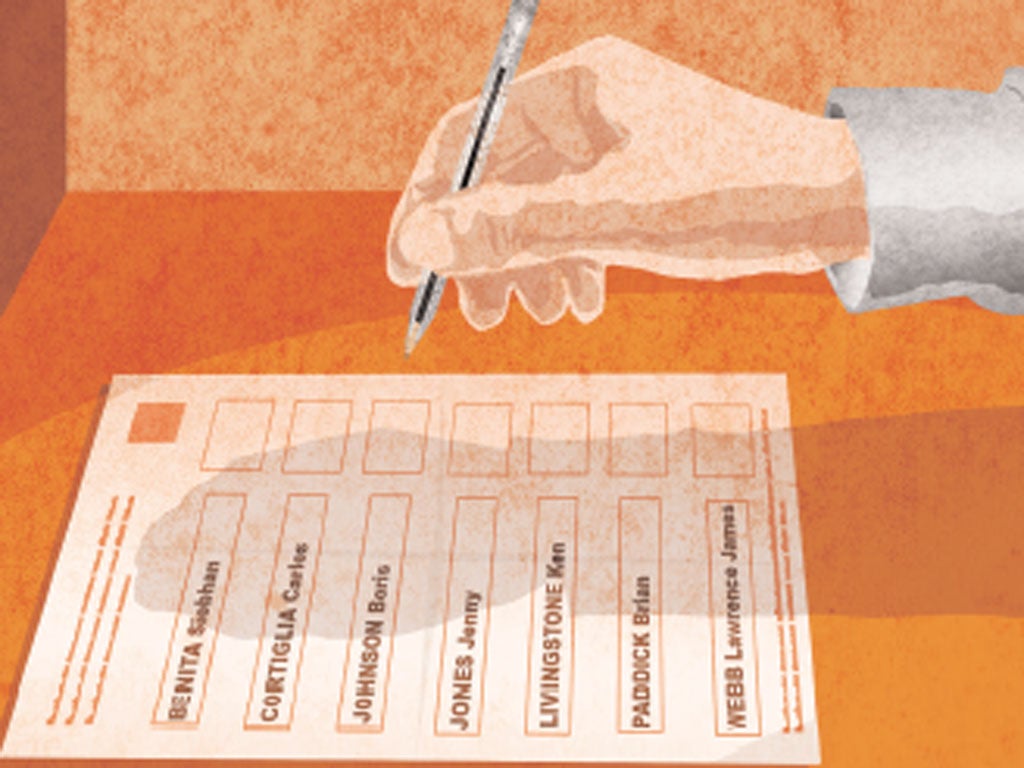

Then there is the argument most often heard in London these past few weeks: that the contenders – all seven of them – are simply unworthy of the great world city they aspire to represent. They're just not good enough for us, the capital's voters – who, as we know, have more higher education per capita than our provincial kin, routinely travel the world, and know our Schoenberg from our Shostakovich. The almost nightly public duels between Boris and Ken – there, I've let slip their names – are mere slapstick, Punch & Judy, for the entertainment of the masses. Vote for any of that lot? You must be joking.

The arrogance that underlies such sentiments is of a piece with the exclusivity claimed by those who fought each and every extension of the franchise. And it boils down to the view that one-person, one-vote democracy is a bad thing, because anyone can have a say and everyone has to be wooed. It lets the riff-raff in, in other words.

Only one group has a legitimate complaint against the spread of elected mayors – well, legitimate in their terms. And they are the elected councillors who have in the past selected the mayor from among their number. A direct election limits their power of patronage and stifles their own prospects, especially in long-standing one-party boroughs. This is why so many of the referendums to be held next week – on whether to introduce an elected mayor at all – are doomed to fail.

These campaigns have been couched in the same terms as those for mayor, with the same spurious arguments about expense and the incompatibility of elected mayors with "our" way of life. But what it comes down to is power, as it so often does. Those who risk losing it are campaigning to keep the status quo, and playing on voters' inbuilt fear of change. And such is the scorn in which local democracy is held – the turnout in local elections hovers around a disgraceful 30 per cent – that they are quite likely to carry the day. The office of elected mayor in Britain is still in its infancy.

Not, of course, that elected mayors are the solution to each and every local difficulty. But to hold up London as an example of why they are a bad idea is to show an almost contemptuous disregard for the real changes that the city's two mayors have brought, and the way the office has evolved since 2000. First, London has a face, in a way it never has done in living memory. There was always room for confusion between the mayors of individual boroughs and the Lord Mayor of London. Those days are over. There is now one mayor of London to represent, answer for and promote the city, which has – point two – enhanced its variegated population's sense of being Londoners.

Nor can the two successive holders of the office – those very same Ken and Boris, as it happens – be accused of not using the power at their disposal. Within the limits of their jurisdiction and budget, they have imposed their mandated priorities and stamped their identity on the way the city works. Ken brought in the Oyster card and the Congestion charge – on time, on budget and without serious technical hitches. Both mayors became advocates for buses. Both tussled with the management and financing of the Underground. Boris banned alcohol on public transport, prompting a glorious, quintessentially London, last-night booze-up on the Circle Line – and astounding obedience thereafter. Boris capitalised on Ken's plans to imitate the Paris Vélib', which has morphed into the hugely successful Boris bike. Bendy buses are almost gone; a new rendition of the beloved Routemaster awaits.

Boris's fights with the Home Office and Scotland Yard, about who had ultimate authority over the Metropolitan Police, were the surest sign yet of the serious power the office of mayor is accruing. Similar, even more ruthless, battles could usefully lie ahead with individual boroughs over housing and planning. The mayor's problem is not too much power, but too little. Squeezed between central government and London's local councils, his is an office still defining itself.

Developments in London are being watched, and reproduced, elsewhere. They are also influencing the national agenda. Jenny Jones, the Green candidate, may have changed British politics for good when she challenged Boris and Ken to settle their tax argument by publishing their returns. Not only did the candidates respond, but the Chancellor said he had no objection in principle to similar disclosures being required of others standing for elected office.

It is highly unlikely that anything similar would have happened during a general election campaign. And the whole point is that mayoral contests, like the qualifications for mayor, are different. For all the sneering about superficiality and circuses, they are as much about character as about policies and party. The mayor is not an MP. He has to hold his own, solo, on the national and international stage, which helps to explain why such party stalwarts as Michael Portillo (Con) and Lord Sugar (Lab) have forsaken their traditional allegiances during the campaign and why Londoners have been queuing around the block to take part in hustings and debates. Without a mayoral election, there would be no such political flux and no such engagement.

This time next week, local election counts will be well advanced across the country, with much attendant rune-reading for the next general election. The mayoral contests by contrast will have clear victors and immediate agendas. And London will know whether its future is Boris or Ken.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies