Ashes 2015: How the first Eleven opened the door to international touring

As Michael Clarke’s Australian team arrives on these shores in pursuit of Ashes glory, John Lazenby recounts the exploits of the ‘strangers’ who in 1878 arrived from Sydney and inaugurated what became the tradition of Test match series

Seventeen Australian cricketers flew into London this week accompanied by an arsenal of equipment and a support staff of more than 20: eight coaches, a manager, a media manager, a trio of selectors, two doctors, a couple of physios and five masseurs, the latter responsible no doubt for the prized quintet of fast bowlers, upon whose form and fitness the destiny of the 69th Ashes series is almost certain to rest. All the accoutrements of a modern touring team, but an embarrassment of riches nonetheless.

If there is a burning hole in the bulging kitbags of the Australians, however, it is the fact that they have not won the Ashes on English soil for 14 years.

When the first representative Australian cricketers disembarked at Liverpool on 14 May 1878, for the inaugural first-class tour of England by an overseas team, they could not even run to a baggage man. In fact, they barely had a squad. These were simpler times, of course. International sport was no more than a gleam in the eye and The Sporting Times’ celebrated obituary for English cricket, lighting the touchpaper under the Ashes legend, was still four years away.

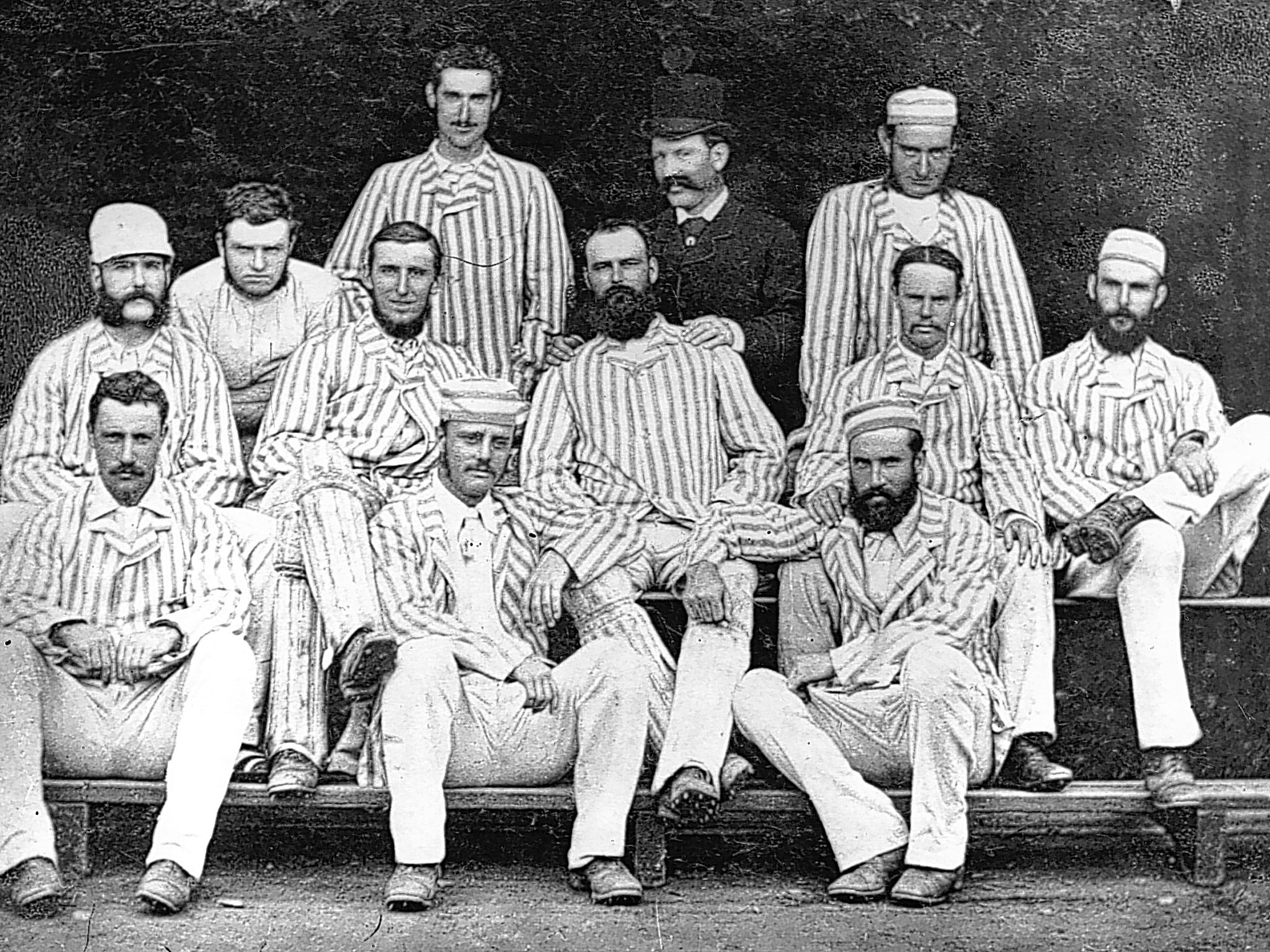

Yet the 11 (yes, 11) pioneers who sailed from Sydney for England, via San Francisco and New York, had to draw lots to decide who would carry their giant canvas bag of equipment, or the “caravan” as it was called. The object of their mission was equally modest: “to measure themselves against the English players on the classic grounds of the Old Country”. As statements of intent go, it was hardly designed to strike fear into the hearts of their opponents.

A year earlier Australia had defeated James Lillywhite’s professionals (the fourth English team to tour Australia) by 45 runs at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The Grand Combination Match, as it was billed, was later designated as the first Test match played between England and Australia. Lillywhite’s men were overwhelming favourites and bet heavily on themselves to win, but they had not bargained on the New South Wales batsman Charles Bannerman. The Kent-born opener played one of the most destructive innings of his or any other era, hitting 165, more than two-thirds of his team’s runs in a first-innings total of 245. Chasing 154 to win on the fourth day, England were routed for 108 in a little over two hours. It was in the full flush of victory that an Australian plan to tour England was hatched.

The prime mover behind the venture was Jack Conway, the organiser of the Grand Combination Match. Conway has been variously described as a sportsman, journalist, entrepreneur and maverick, but he was also a formidable fast bowler, who played for Victoria from 1861 to 1874, and a fearsome Aussie Rules footballer. For all his brawn, though, he was a cultivated man who liked to swear at his players in Latin (not something you might expect to catch Darren Lehmann doing). He established himself as manager, selected the team and appointed David Gregory, a tough-minded Sydney accountant, as captain. He also formed a cooperative association in which each member paid a £50 stake, and arranged a preliminary tour of New Zealand and Australia.

It took The Eleven, as they now referred to themselves, almost seven weeks to reach England – a journey that included a potentially hazardous trip by rail from San Francisco to New York at a time when train robbery was a regular occurrence. They arrived in New York unscathed after a “very tiresome” week on the railroad and boarded the City of Berlin, docking in Liverpool nine days later. Their arrival on the quayside was low-key, leaving them unprepared for the huge crowd that jammed the streets of Nottingham, where they played their opening match. As a team of Aboriginal cricketers had visited England 10 years earlier, many of the crowd expected Gregory’s men to be no different, and one of The Eleven recalled an onlooker exclaim: “Whoy, Billy, they bean’t black at all; they’re as white as whuz!” When they lost to Nottinghamshire in the rain, wind and mud of Trent Bridge, some of the Australians were convinced they had landed in the midst of the football season.

No one gave them a chance in their next match, against an MCC side at Lord’s including the Champion of England himself, W G Grace. So much so that when Grace struck the first ball for four, the crowd openly laughed. However, in attempting to repeat the shot next ball, Grace spooned it straight into the hands of square-leg. Four-and-a-half hours later MCC had been spectacularly defeated, dismissed for 33 and 19 by the legendary fast bowler Fred Spofforth who, in recording the first hat-trick by an Australian in England, earned his moniker “The Demon” and match figures of 10 for 20 from 14.3 overs. The tourists’ nine-wicket triumph remains to this day one of the most remarkable upsets in sporting history, the catalyst for the modern game and the point at which England’s interest in international sport was first piqued.

From then on the “strangers”, as they were dubbed, were in huge demand. For the next four months they criss-crossed the country by train, mostly through the night, playing in such far-flung cricketing outposts as Glasgow, Swansea, Burnley, Scarborough and Hastings, often on little sleep and sometimes against teams of 18 or 22. The names of Spofforth, Bannerman, Jack Blackham, the brilliant wicketkeeper who stood up to the stumps to fast bowling, and Harry Boyle, the inventor of silly mid-on, became common currency. In all they played 37 matches in Britain and a further 35 on their travels through Australia, New Zealand, Canada and America.

Each man was said to have received a windfall of some £750 from his £50 investment (worth about £64,000 today) on their return to Sydney, where they were greeted by a cheering crowd of 20,000. More significant by far, however, were the legacies of their expedition. By introducing a “new brand of Australian cricket to the English market”, they changed the game for ever, setting in motion the traditional cycle of international tours, the birth of the Ashes and the advent of the Test match age.

If Michael Clarke’s squad should find themselves seeking inspiration during their three-month tour, they need look no further than The Eleven of 1878 and a summer when the “fame of Australian cricket was established for all time”.

--

Name of the game - Waugh Jnr gets call-up

It may soon be time for the Australia cricket team to come up with a new and witty nickname for another Waugh, after Steve’s son Austin was called up to the national Under-16 squad.

Steve was known as “Tugga” during his playing days, while his less-heralded brother Mark was known as “Afghanistan” – the forgotten Waugh.

The 17-strong squad which features Waugh Jnr will play at the Under-17 national championships in the southern hemisphere summer later this year. National talent manager Greg Chappell, a former Australia captain, said the exposure at national level will help them in their development.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies