James Lawton: From McDowell to Iniesta: the stars who saved 2010

Our writer reflects on a frequently grim 12 months in sport but takes succour from the likes of Amy Williams' golden moment and Spain's uplifting World Cup triumph

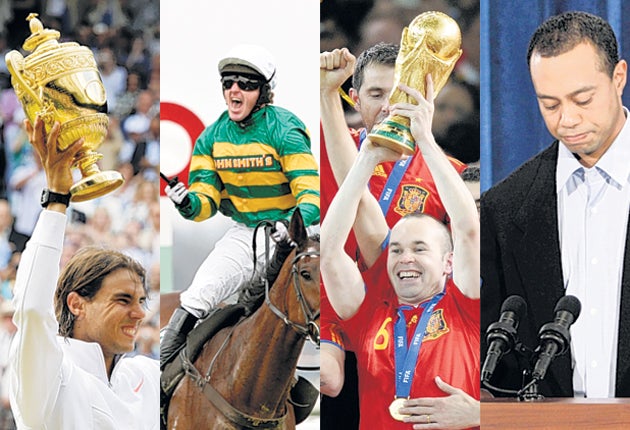

Sport always lights a candle in the wind, even when it is blowing most bleakly, and this passing year was no exception: it gave us, supremely, Andres Iniesta winning a World Cup and confirming the brilliance of Spanish football, and also Rafa Nadal and Manny Pacquiao.

It offered Graeme McDowell's Ryder Cup-winning putt and Tim Bresnan's decisive Ashes delivery and Lee Westwood's reward for stopping and thinking about who he was and who he might be – the top ranking in world golf – and there also the thrilling sight of the mad, magnificent West Country girl Amy Williams hurtling down the ice for gold and Mark Cavendish sprinting phenomenally in the Tour de France.

There was also A P McCoy, winning the Grand National and at last recognised by the British public, but then of course there is always A P McCoy.

There is little point, though, in avoiding a darker issue.

Perhaps as never before had we been in greater need of such joyous and rejuvenating images of superb sportsmen and women. They were, after all, a counterbalance to the sometimes overwhelming sense that sport had never been so poorly directed, never so rotten in its defence of something that has always been capable of lifting the mood of all people, however oppressed and disenchanted.

You could take a blindfold and stick a pin in the map of sport and find reason for despair.

You might land it in Twickenham, and see the appalling evasions and amorality that came in the wake of the Bloodgate scandal. You might settle on Zurich and revisit the monstrous deliberations of Fifa in its assignments of World Cups stretching all the way to 2022, leaving the world's greatest sports event all locked up for no better reason than money had spoken again in a hard and most cynical voice. You could drop the pin in any Formula One circuit and find machinations which shamed the concept of competitive sport.

You could stumble upon Old Trafford and find Wayne Rooney, in the year in which he had come down from the mountain top to a poverty of form and behaviour, holding Manchester United up for ransom. Just a few miles across the city you could consider the nadir of professionalism represented by the posturing of Carlos Tevez.

For some of us, though, the most haunting image of all came in the beautiful city of Vancouver, when representatives of the British Columbia Coroners Service, the International Luge Federation and the International Olympic Committee lacked only the bowl of water and the towel of Pontius Pilate when they pronounced on the death of the young Georgian luger Nodar Kumaritashvili.

They announced that Kumaritashvili, who had been permitted only a fraction of the practice runs granted to the host nation Canada, had caused his own death and there was no deficiency in the Whistler Mountain run that had already been described as the fastest and the most dangerous in the world. Kumaritashvili, the officials declared, had failed to "compensate" sufficiently at the fatal bend.

So why was the track shortened and made safer and the conditions of racing changed so profoundly? Because of the shortcomings of one poorly prepared fringe competitor? Or because the truth was quite different, and already expressed by the manager of the powerful American team, who said that the limits of safety had been pushed dangerously in the building of a track guaranteed only to be spectacular?

When the boy's father took possession of his son's body – and the President of Georgia came to the poor mountain village – he said: "I wanted to throw a wedding feast for you, instead you had a funeral."

A few days later Tiger Woods stood up at an entirely different social occasion in Florida and made a mea culpa for an adulterous past which had been fastidiously concealed.

There was much preachy reaction to his plea for forgiveness, many claims that his strings were pulled by his corporate investors, and one American commentator declared, "Tiger, I don't accept your apology," but then who was drawing the moral parameters, and who in the running of sport could claim entirely clean hands?

Not the cricket authorities, certainly, when the Pakistan spot-fixing disaster plunged the game into a fever of doubt. Mohammad Amir didn't lose his life, not like the tragic Kumaritashvili, but it was diminished, terribly, and could be held up as a shocking example of how sport had neglected to provide care and example for one of its shining assets.

Amir bowled beautifully at Lord's on the eve of his downfall, but now he was a pariah, treated with outright contempt by Giles Clarke, the chairman of the England and Wales Cricket Board, who had so recently and warmly embraced the patronage of a man who was later charged by the American authorities with massive fraud.

It meant that you were required both to cherry-pick and hoard the moments of redemption.

One of them, in the gloom of England's shocking failure in the World Cup, was the ability of Iniesta and the Spaniards to carry a torch for the beauty of football, and the ability of some its most gifted players, to deliver the best and the most creative of talent. Had the Dutch, who had promised so much more, won with their thuggish approach to the final, it would have been an unspeakable crisis for football. By year's end the game could not escape such a fate, but that was not the work of Iniesta, the Little Man from La Mancha, but Fifa president Sepp Blatter and his cronies.

They made their big money in South Africa, quite relentlessly, which made it doubly poignant that the South African people, for all their difficulties, still produced a magnificent statement about the value of the tournament that now, in the most dubious way, has passed into the control of the highest bidder.

One of the most unforgettable sights in South Africa came on a drive back to Johannesburg from the Soccer City stadium.

It was of a young African, quite alone, standing on the brow of a hill looking down on the sweep of the valley stretching back to the stadium fashioned in the shape and the colours of a great cooking pot. He was very still, very slim and lithe. He appeared, from a distance, as though he was capable of running great distances. But now he stood and looked down so impassively.

He might have been a South African version of Nodar Kumaritashvili or Mohammad Amir. He might have been entertaining dreams of his own. If he was, we know well enough how perilous they were. But then we also knew, reassuringly, that he would be right to pursue them.

Sport may not be blessed by the quality of so much of the leadership it receives, it may be overly receptive to the forces of greed and ruthlessness, but there is something about it too strong, too inspired, to be permanently compromised.

Just when we suspect that it may be so, an Iniesta goes on a run, a Pacquiao delivers a one-two combination that shakes the earth and Kevin Pietersen, daft old KP, hits a straight drive that might have come out of the barrel of a gun. Then we know the games we play will make it to another year, still alive with the possibilities of glory, still promising the world.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies