The Last Word: Harsh reality of destroying boys’ dreams

Teenagers must be handled with care when let go by clubs – their whole world has collapsed

Josh Lyons never recovered from being released by Tottenham Hotspur. His failure to re-establish himself at Fulham and Crawley Town intensified the cycle of rejection and depression. One day last year, after telling his parents he was going jogging, he walked out of the trees and into the path of a train on the line from London Victoria to Portsmouth.

The coroner concluded that leaving Spurs, his childhood club, at the age of 16 was the “pivotal point that crushed a young man’s life and all the dreams that go with it”. She called for football to do more to look after its own.

Reports of the inquest featured a photograph of a young boy with floppy hair and a bashful smile. Josh was wearing the kit of his first professional club, Wimbledon. His team-mates staged a memorial match, where he was remembered as a fast, nimble striker and a caring individual who once couldn’t afford to get home because he had given a beggar his train fare.

Tottenham sent their condo-lences. Their academy programme is one of the best, offering holistic educational support and advice on alternative careers. The authorities, reshaping youth football through the contentious Elite Player Performance Plan, insist they take their duty of care seriously.

Fabrice Muamba works with emerging players on behalf of the Professional Footballers’ Association. His message – “You never know when the game is going to be taken away from you” – is apposite, poignant because of his brush with death, but diluted by the blind faith of youth.

Too many boys define themselves by their football ability. It is central to their self-esteem and underpins their social networks. Rejection is devastating, especially when they return from distant clubs to the com-munities which nurtured them.

Easter is the time teenagers complete the trudge towards their personal Calvary. At least 400 scholars, young players on essentially two-year apprenticeships, have been told over the past fortnight that they have failed to earn a professional contract.

Many more have been released at 16, when scholarships are normally offered. Of the 10,000 or so boys in the academy system, only one per cent will make a living from the game. Two thirds of those who sign professional forms are out of football by the time they are 21.

Destroying dreams is a dreaded duty, routinely described as the worst job in football. Some clubs write rejection letters containing offers of a voluntary debrief, so that boys can deal with the blow in the bosom of their families.

Others choose to deliver the bad news directly. Some youngsters want the ordeal to be over as quickly as possible; others linger and siphon the pain through staccato bursts of rationality. Coaches’ consciences are stirred by boys who are so distraught they lose any semblance of control; as one reflected: “We are fathers too.”

Many, like Gary Issott, manager of Crystal Palace’s highly regarded academy, recognise the importance of the pastoral care provided by the League Football Education programme, but feel more can be done.

He estimates it takes even the most well-adjusted boy at least two years to recover a sense of equilibrium: “You help as much as you can with exit routes, but the next batch of players needs all your attention.”

More than 200 survivors will submit themselves to the scrutiny of scouts in four separate exit trials, hosted by Bradford City, Staines Town, Port Vale and Walsall from 1 to 8 May. They will have three 50-minute matches in which to salvage a future. “What gets me is how many don’t bother,” said one of the few Premier League managers to be proactive in the process. “They want nothing more to do with football. It is as if the life has been sucked out of them.”

His sentiments were honourable, but their hidden implication was telling.

Bitter rivals give peace a chance

Football is defined and occasionally defiled by its tribalism. The rivalry between West Ham United and Millwall is bitter and bloodstained.

The enmity of clubs forged by similar working-class principles can be traced to their presence on either side of an ancient divide, as Thameside dockers or shipbuilders.

Matches between the two clubs are a threat to public order. Millwall, in particular, are stigmatised by their association with violence.

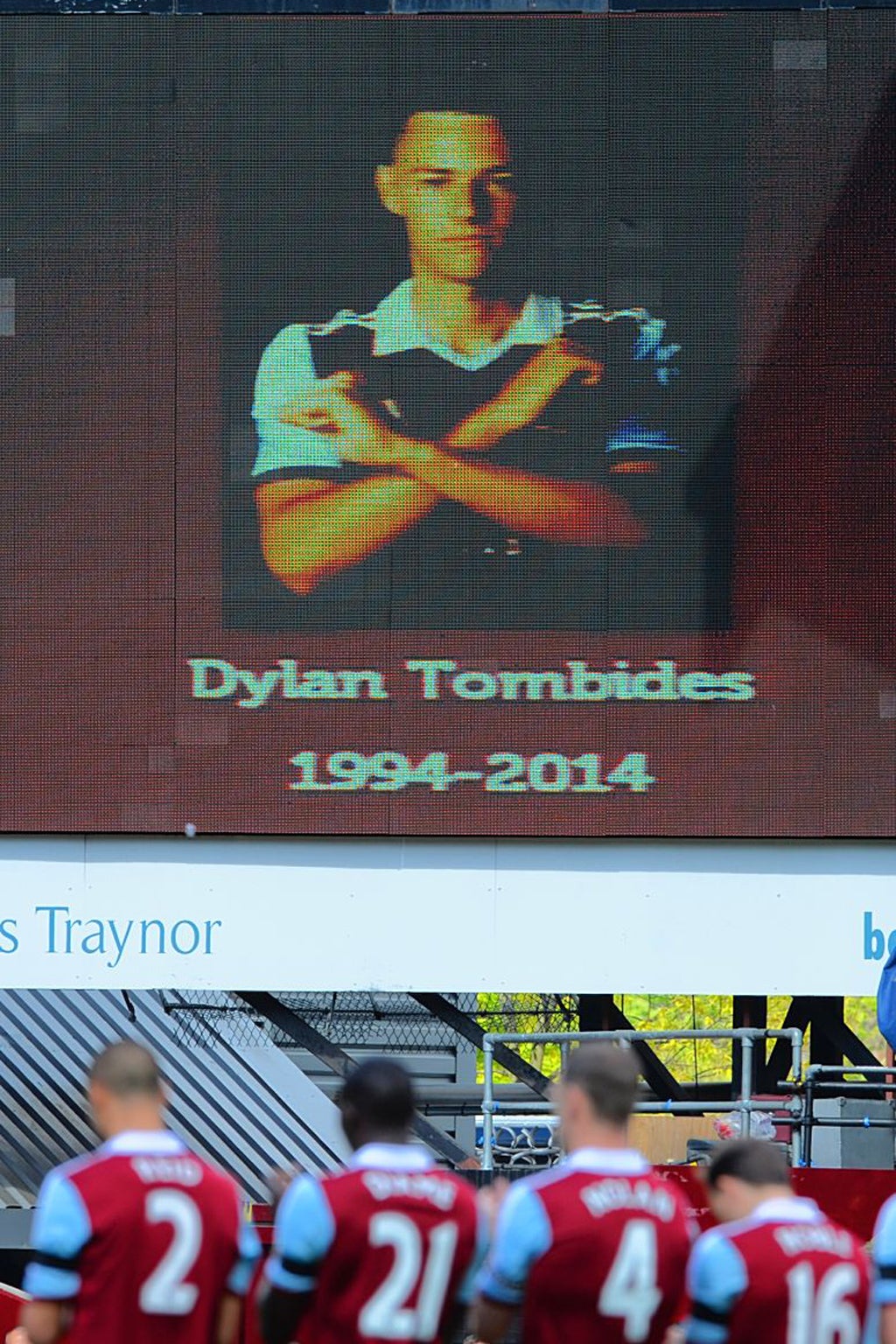

Why, then, are Millwall fans making a collection to provide a tribute to Dylan Tombides, the West Ham player who died from testicular cancer, aged 20, on Friday?

Why are West Ham supporters signalling their gratitude and respect for such instinctive humanity across the tribal barricade?

It is principally a reminder of the danger of stereotyping. Stripped to its basics, football still enshrines a common decency. The rest is just noise, meaningless posturing.

It shouldn’t take a tragedy to give peace a chance, but perhaps it is the epitaph Dylan deserves.

Tykes’ Tour takes road to banality

Curses of modern sport (Part 438): The Official Event Song. The start of this year’s Tour de France in Yorkshire will supposedly be enriched by an anthemic dirge entitled “The Road”. At least “On Ilkley Moor Baht’at” would have had cultural credibility.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies