No ghosted autobiography can match the nuanced insight of the latest book on Bobby Moore, a hero flawed by alcohol

New book leaves us with a sense of an extraordinary magnetism and ability

A very uneasy moment materialised towards the end of the conversation with Roy Keane. The question of his fight with alcohol – the one that he said in his first autobigraphy was “a big problem I have; a major problem” – had dared not speak its name across half an hour of questions about his second memoir last week and it needed to be broached.

Finally, with a flinch, it was. And Keane paddled it away as an inconsequence. “The beauty of the book [is that] I don’t have to explain everything to you,” he replied. “That’s not what the book is about...”

So there we had it: the fundamental flaw in Keane’s new and lucrative literary partnership with Roddy Doyle. It is an attractive combination and there is self-satisfaction on Keane’s part that he has escaped the “standard sportswriters route” and placed himself on something of a “psychiatrist’s couch” with a Booker Prize winner. But when the booze cropped up in our conversation Keane had nowhere to go. He and Doyle had not addressed it so how possibly could Keane and we?

“None of your business,” some with a distaste for that kind of journalistic scrutiny will say. Enough to know that he seems to have kicked the drink. But here was the chance for one of football’s deities to reach the many helpless souls whom that self-same struggle has left behind.

And to offer a self-portrait incomparably more nuanced than the stand-up rows with Carlos Queiroz and a hotel corridor fist fight with Peter Schmeichel, fascinating though it was to know that Sir Bobby Charlton was awoken by the punching, walked out to see it all happening and went swiftly back to bed.

It’s the compact between writer and subject that is the trouble with ghosted autobiographies. Compromise is at the heart of the arrangement and, in the case of Keane and Kevin Pietersen last week, you see significantly less than half the man.

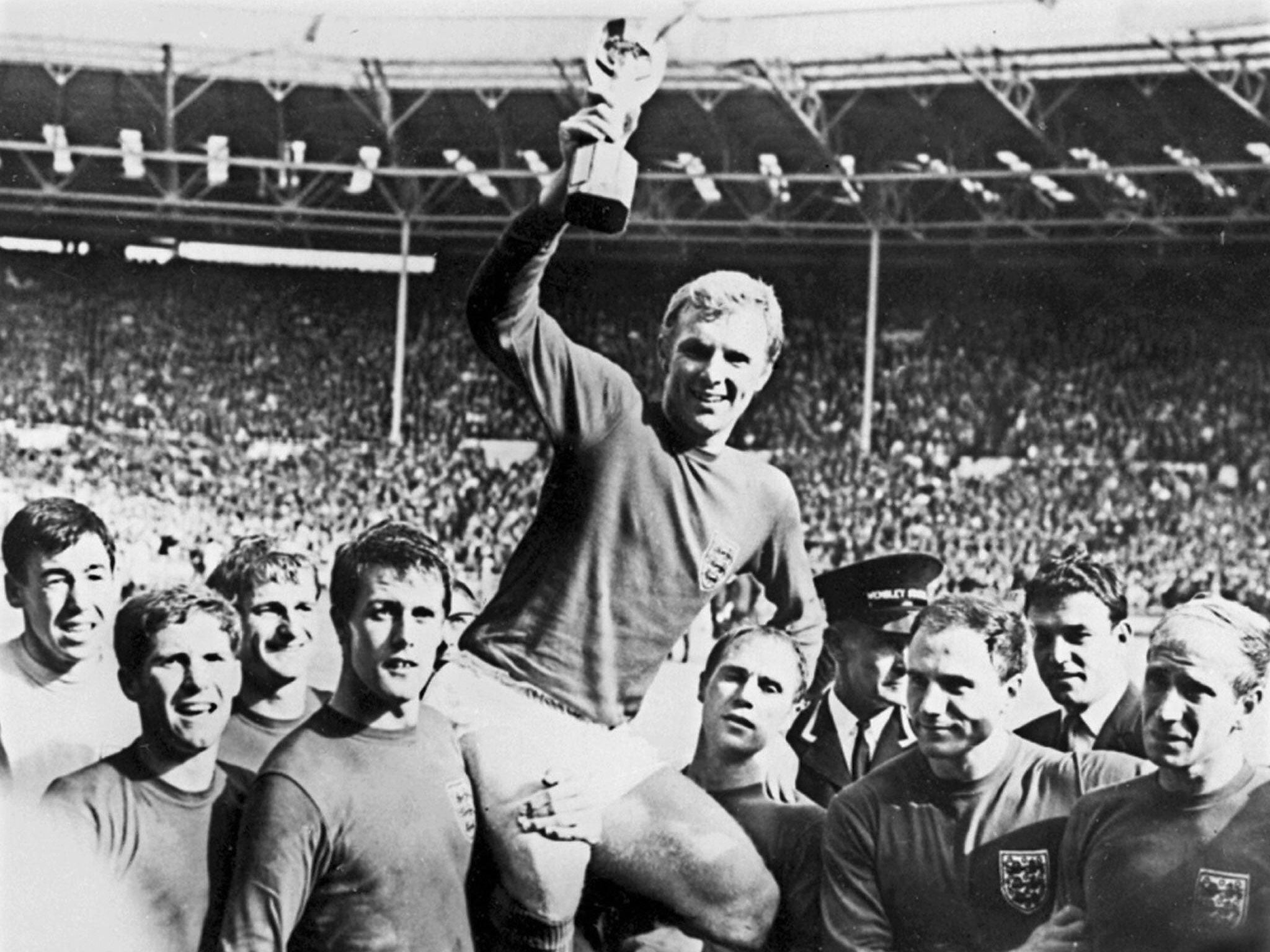

Read the new biography of Bobby Moore by the Times journalist Matt Dickinson and you’ll find what you are missing. Dickinson’s book is appropriately titled The Man in Full and though Moore’s family has cooperated substantially with this daunting piece of journalism, the professional distance allows a perspective. The book exposes the narrowness of those selected for the razzmatazz of publishing’s pre-Christmas “Mad Thursday” last week.

Alcohol belongs in Moore’s story too – and how. Dashes into the shop on the Crewe station platform for crates of lager when the Pullman from Manchester paused on the way back to Euston on Saturdays; the peaked chauffeur’s cap Moore wore to make it less likely he’d be pulled for drink-driving in his red Jaguar XJ6; crashing his Daimler Sovereign into a bollard while three times over the limit and with his nine-year-old son in the car. There is as little heroism in these stories as in Moore’s catastrophic business decisions, his association with the Krays and the mickey-taking of Sir Alf Ramsey. But it is still a sense of an extraordinary magnetism and ability that the book leaves us with.

Dickinson tells how his subject would pay serious Sunday morning penance for the boozing – arriving at a deserted Upton Park in boiler-suit, sweatshirt and bin-liner looking like the Michelin man. “Moore would trudge around for three quarters of an hour, the booze seeping out.”

The story of how Moore, the meticulous and immaculate epitome of London chic, developed testicular cancer at the age 23, did not deal with the signs for a year, and was so determined his team-mates must not have known that he sidled into the showers with his back to the wall to hide the marks used to guide his radiotherapy, is the kind testimony which perhaps only a work of journalistic biography would tell.

His same aversion to talking about himself lay behind the series of valedictory phone calls Moore made to his friends after “the day he found out that his bowel cancer was terminal”, to quote the devastating opening sentence to Dickinson’s book.

The stories are relentless about a man always loved for his coolness. When his clearing header knocked referee Gerrard Lewis on the back of the head – and momentarily unconscious – during a match against Wolves at Upton Park, the game continued, with tackles flying in. “Moore clamly bent down, picked up the referee’s whistle and brought the match to a halt,” Dickinson relates. “Typical Bob,” Trevor Brooking tells him. The Man in Full is as flawed as us all but a hero above all.

The book recalls to mind Duncan Hamilton’s Immortal, the George Best masterpiece written with the cooperation of another legend’s family last year. In the same genre, Philippe Auclair’s Lonely at the Top, on Thierry Henry, revealed the depths that can be reached when the writer’s feelings for his subject are complex. Auclair loves the player; he is not so sure of the man, who detested criticism and displayed rather a lot of calculation.

The work required for autobiography to come close is vast. Michael Calvin drove Gareth Thomas around the landmarks of his life – clifftops, graveyards, Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium, the back-to-backs of Sarn, near Bridgend – over the course of several years to bring out the story recently told in Pride. The result is a work like few others, now inviting justifiable comparisons with Marcus Trescothick’s Coming Back to Me. The common denominator being that those sportsmen had crossed huge frontiers and wanted to say how. Both books have changed lives.

Doyle told me last week that he’d never known a literary process of such breakneck speed as this one: an email proposition received in November, meeting with Keane in December, work starting in January, finished by June. “It’s quite amazing,” he said. “Usually for me a novel is the work of years; a couple of years.” The life of Roy Keane deserves no less.

What would Rooney have got if he had done a Flower?

As an enthusiast for rugby league – he’s a Leeds Rhinos fan – Wayne Rooney might have grimaced at the sight of Ben Flower, two minutes into Saturday’s Super League Grand Final. Not so much at the flagrant brutality of the Wigan Warriors prop, drawing back his fist and thumping Lance Hohaia flat in the face, but the thought of what the repercussions would have been for him. A cynical, though not brutal, clip at Stewart Downing on the same Old Trafford turf two weeks earlier had planet football dissecting Rooney’s worthiness to be England captain.

Football’s popularity creates the scrutiny. Its players suffer from a ridiculous lack of perspective.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies