Fletcher can take heart from Moody recovery

Rugby player fought back from the same bowel condition to captain England at World Cup

For the impact that ulcerative colitis can have on the life of a sportsman in the prime of his career, the story of Lewis Moody, the former England rugby captain and another sufferer, stands as a stark precedent for Darren Fletcher. For Moody it was a slow road from denial, to secrecy about his condition and on to a painful acceptance that he would have to live with the physical and psychological toll.

In his autobiography, Moody, who resigned as England captain in October after the World Cup in New Zealand, wrote that he believed the condition had been brought on by his over exposure to anti-inflammatories, antibiotics and painkillers which he needed to cope with the demands of his sport. He was first diagnosed with it seven years ago when he began passing blood and the problem became much worse.

As an elite sportsman who did not wish to give the coaches at Leicester or England a reason to drop him from the team, as well as fearing the unforgiving badinage of the changing room, Moody said that he initially covered up the condition. "There was no way I was going to let my secret out to a bunch of rugby players who would then mock me mercilessly," he wrote. "I ended up hiding it from them for three years and I slumped into a state of depression."

With the help of the Leicester club doctor he treated it as best he could but the horrendous effect of ulcerative colitis would have been difficult to keep secret for any young man, let alone a high-profile sportsman such as Moody. The starkest example of the condition's demeaning effect is an incident Moody recalls that took place on Christmas Eve in 2007 when, aged 29, he experienced a bowel movement while shopping in Leicester city centre. Panicking and unable to find a toilet, he soiled himself "in the middle of the street".

"There are few more demeaning experiences for any man, let alone a rugby player," he later wrote. It was from that moment that Moody decided to be more open with his team-mates and he said that in recent years his impromptu departures from the training ground became known as the "emergency crap" – about as understanding as he could hope to expect from his team-mates.

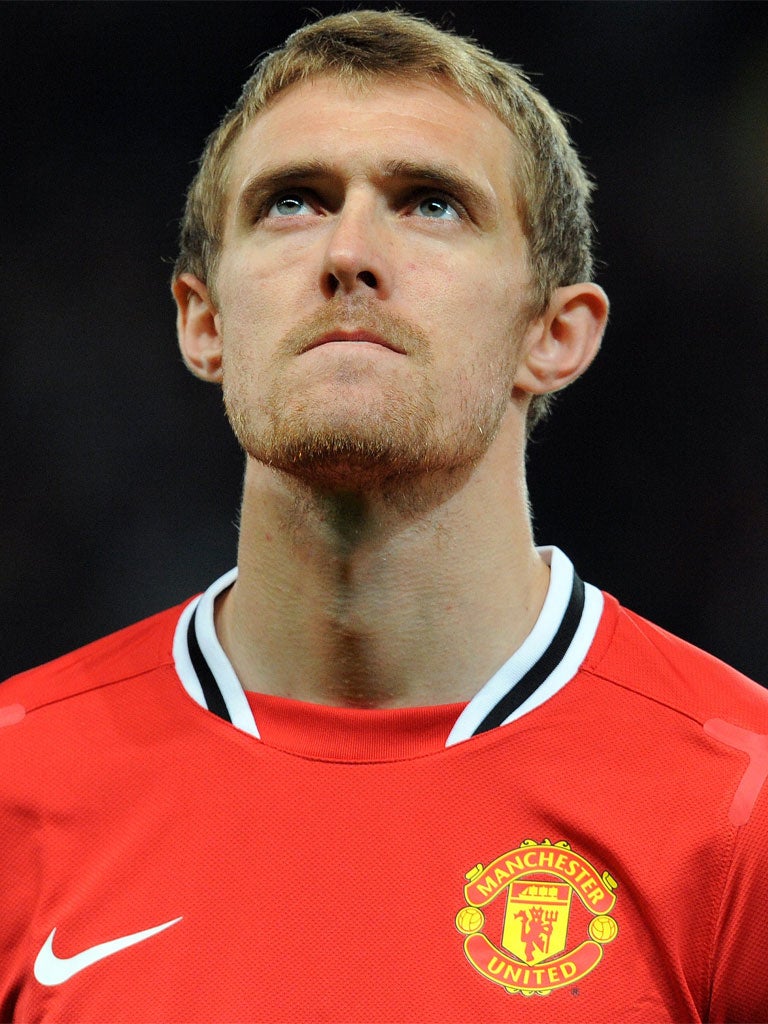

While the extent of Fletcher's illness is not a matter of public record, if his experience has been anything like that of Moody, then the anxiety must have been debilitating for the Manchester United midfielder. The prospect of playing in front of 75,000 people at Old Trafford is demanding enough without having to worry about the likelihood of one's body functioning imperfectly.

Although the exact nature of Fletcher's illness, which struck just before United's defeat to Liverpool on 6 March, has been kept secret until now, the club and player have been open about the effect of Fletcher's weight loss. "I lost close to a stone which for someone like me – I don't have a stone to lose – was massive," Fletcher said in September.

After the game against Liverpool, Fletcher played just twice more last season, at home to Schalke in May and Blackpool on the final day of the season. He missed United's pre-season tour of the United States and his first games of this season were for Scotland in their Euro 2012 qualifiers in September. Since then he has managed just 13 games for United and Scotland.

Since he established himself in the United team in 2003-2004, the season following David Beckham's departure, Fletcher has averaged around 40 first-team appearances a season. He was a key figure in the United team that won three Premier League titles from 2006 to 2009 and, from being an academy player whose career at Old Trafford could have gone either way, he had emerged as a central figure.

If Fletcher's influence has occasionally been underestimated for United, that has never been the case for Scotland. He is the captain of a team that, for the first time in a while, has some promising players at Premier League clubs including Charlie Adam, Barry Bannan and James Morrison. Despite Scotland's problems, Fletcher has always made himself available and, with 58 caps at the age of 27, he is only three off the top 10 of the country's all-time appearance-makers.

Of course, his enforced break from the game puts everything in doubt. However, the disclosure yesterday by Fletcher and United at least brings to an end the rumours circulating about Fletcher's condition. No one can doubt the severity of the condition – one that Sir Steve Redgrave also developed in the 1990s – and the hope is that there may be a little more understanding about its consequences for Fletcher.

Ulcerative colitis is exacerbated by stress. But Moody discovered that as he allowed his team-mates to find out about his condition, that stress declined. His best friend at Leicester, Geordan Murphy, chided him for not being open in the first place. "Being stubborn about it and keeping it a secret had simply made life harder for myself," Moody wrote. Ending the secrecy is one less thing for Fletcher to worry about.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies