The remarkable night Sugar Ray Robinson met his match, recalls Steve Bunce

Flamboyant American was expected to overcome Londoner Randy Turpin at Earl's Court in 1951 but met his match in an epic world middleweight bout

Sugar Ray Robinson had a dwarf called Arabian Knight in his entourage of 13 during his tour of Europe that ended at Earl’s Court in July 1951 after six fights, in just seven weeks, in six different cities and five different countries.

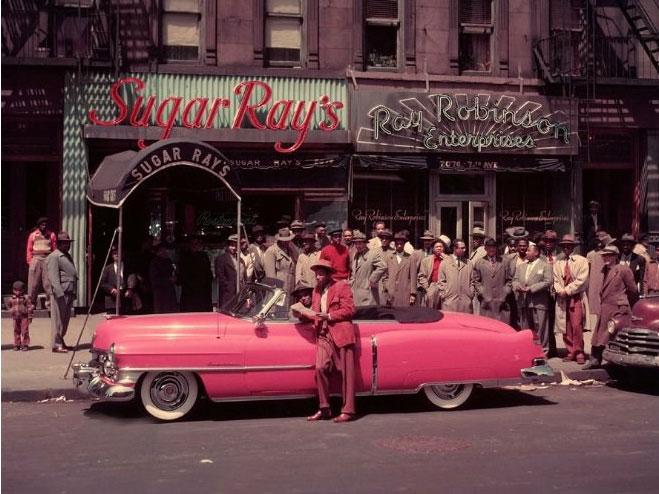

The world’s finest boxer was excessive and back in Harlem there was Sugar Ray’s, his club, his pink Cadillac, his collection of exotic zoot suits, his dapper foot soldiers, but on the road there was the dwarf, a hair dresser, a golf professional, a dance instructor and various men that had jobs ranging from measuring his sweat to teaching him to sing.

The last stop on the European tour for the world middleweight champion was London and a defence against Randy Turpin, a mixed-race fighter from Leamington, whose brother was the first black boxer to win a British title; his father, who was from British Guinea, was wounded in the Somme having been gassed and shot, and died a few weeks after Randy’s birth. Turpin was an outsider in the boxing business, Robinson the sport’s emperor.

Last week a fight between Liverpool’s Liam Smith and Saul Canelo Alvarez, who is probably boxing’s biggest attraction, was announced, and this week Chris Eubank Jr should hear about his planned fight with Gennady Golovkin, arguably the sport’s most exciting fighter. The Turpin and Robinson fight was bigger, a sell-out of 18,000 at Earl’s Court; Robinson had lost just once in 133 fights, boxed nine days before meeting Turpin and held open court at the Star and Garter pub in Windsor where he stayed with his entourage. The fighter travelled like a medieval sultan, with secrets in each tent and alluring women barely out of the shadows when the touring party pitched their carnival.

When asked how he thought the Turpin fight would end by a pack of mesmerised hacks, who had camped at his training base to marvel at the exotic retinue, Robinson was brilliant: “Well, I’d like it to be just one round. But they tell me that Turpin won’t co-operate. So, I guess, that it won’t go more than 15 rounds.” He was right, Turpin did not co-operate.

On the day of the fight Turpin made his way down from Leamington by train. Robinson filled limousines. At the venue the seats were full and Jack Solomons, between chomping on a swollen cigar, smiled the smile of a satisfied promoter. It was quite incredible what happened once the first bell sounded; the massacre was off, the dancing master was a step behind and Turpin went the full 15 rounds to become world middleweight champion.

“It’s not the fights that tire a man, but the travel,” admitted Robinson. “Turpin beat me fair, he was the better man. It’s that simple.” It was Robinson’s second loss and his mastery in the fight at Earl’s Court was matched by Turpin’s desire; it was a real fight, perhaps the finest performance ever by a British boxer.

In the melee to swarm Turpin and his tearful brothers, there is no record of the passage from their gloomy ringside trench back to Windsor for Arabian Knight, the masseur, the golf pro, the dance instructor, the singing coach, the hairdresser with his faded pomade, or even the man the French called the Black Angel. Robinson was beaten and he vanished with his lost souls, never uttering a word as an excuse.

Poor Randy never settled, never enjoyed the life. There was a rematch at the Polo Grounds in New York just 64 days later, watched by 61,370 people and Turpin, after nine mediocre but even rounds, was stopped in the tenth. Robinson was champion again and would fight on at elite level until 1965. Turpin fought his dreadful wars on both sides of the ropes until May 1966 when he took a gun, found an empty room above the transport café his second wife ran and left a savage note to a business that never fit him. His last letter was ripped from the bottom of a broken boxer’s heart, ending with the line: “We’ll watch the next man – just one more fool.” He shot himself that day. Robinson had been retired less than six months, his brain already starting to shatter silently away from detection after 200 fights and 25 years as a professional boxer.

Mad Olympic dreams.

Amnat Ruenroeng lost his world flyweight title in May and will now jump six professional weigh divisions, a total of over 25 pounds, to fight as a lightweight in this week’s final Olympic boxing qualifier taking place in Venezuela. He is the best of a mercenary batch of professionals fighting for an unlikely place in Rio.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies