Pat Eddery: Shy legend of track who lost his way

Pat Eddery’s early death after battling alcoholism was a distressing end to a glorious career, says Nick Townsend

In death, all but the gravest weaknesses invariably receive absolution, judgements are placed in suspension and eventually airbrushed from memory. It makes the candour of Pat Eddery’s daughter Natasha in recalling her father’s final years a rare and courageous gesture.

Her father, who passed away aged 63 on Tuesday after a suspected heart attack, was to the remainder of us a sporting phenomenon spanning four decades, but not one to propel his ego into the public consciousness. He was certainly never a man to exhibit Frankie Dettori-like exuberance – though there were a multitude of occasions on which he could have been forgiven for doing so – nor was he regarded with quite the awe of the enigmatic Lester Piggott, that merciless pillager of major prizes.

The son of Newbridge, County Kildare, was the supreme professional, never one to engage in histrionics in victory or defeat. Ray Cochrane once analysed the discipline of his former weighing-room colleague, who partnered 4,632 winners in the UK in a 36-year career, a record only exceeded by Sir Gordon Richards, thus: “The way he conducts himself is like the way he watches his weight. I’ve never seen him finish a sandwich, a whole meal or a cup of tea. And I’ve never seen him lose his temper.”

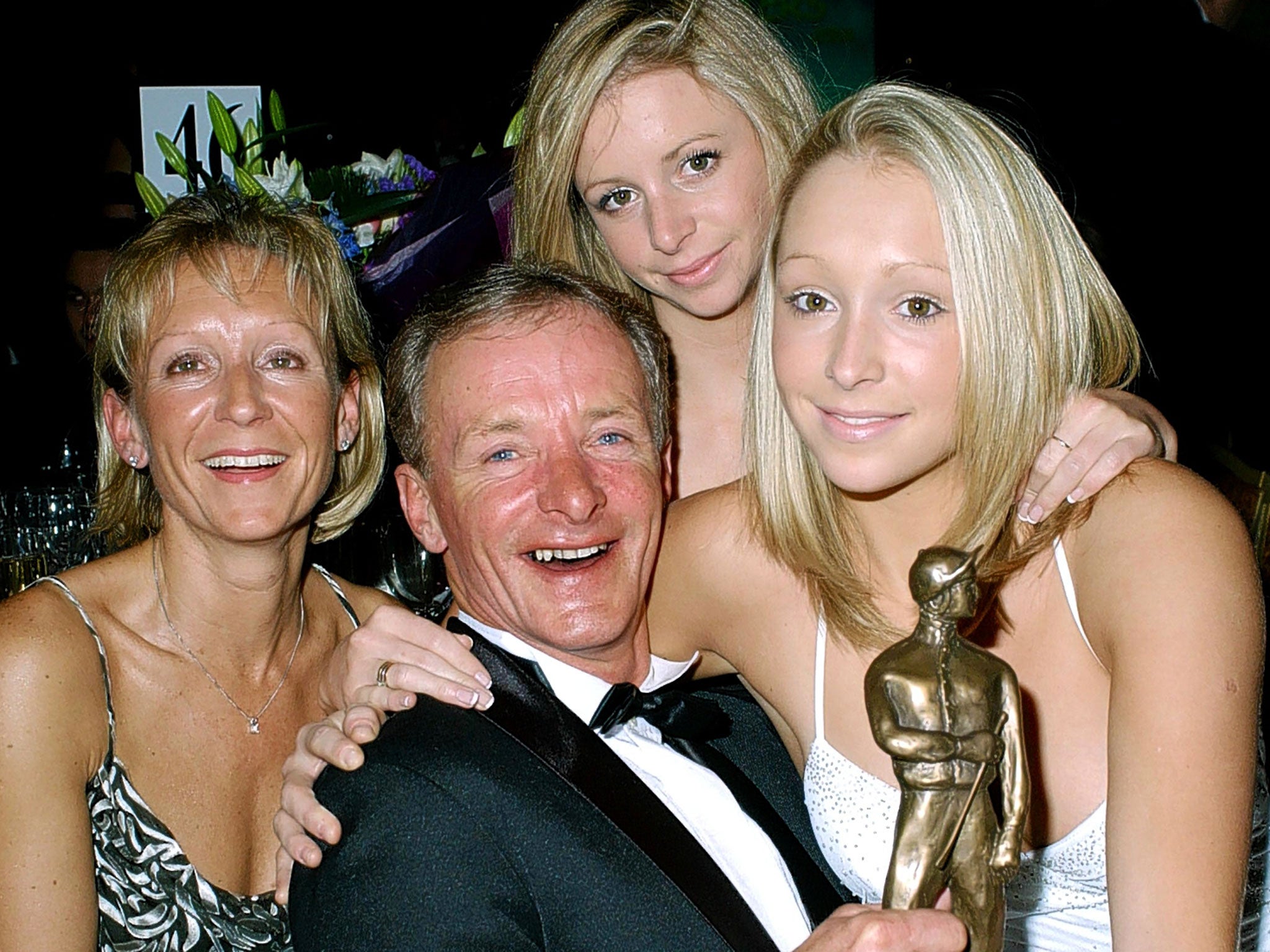

Many daughters would have restricted themselves to talk of family memories, and fierce pride for the man who between 1974 and 1996 was 11 times champion jockey, and won 14 English Classics, including three Derbys. Natasha did all that, but what preceded it was riven with anguish. No euphemisms. No softening of the reality. Natasha posted a heartfelt message on social media, stating that she had not seen her jockey-turned-trainer father for five years after failed attempts to help him conquer alcoholism.

Asked to explain why on BBC TV’s Breakfast programme, she said: “It was a difficult topic, but… I was shocked that people didn’t know he had a drink problem. We didn’t want to disgrace him or anything. My sister [Nicola] and I just wanted people to know how he died… it may raise awareness and make a difference.”

Alcoholism is a disease that has preyed on too many of this rare breed of horsemen, and often it has started because weight control is an essential part of a jockey’s CV and alcohol one of the most convenient ways of sating hunger.

Sometimes there have been other factors. It is said that socialising with owners and trainers brought a premature end to the career of one of Eddery’s key rivals, the American Steve Cauthen, the so-called “Kentucky Kid”, whose union with Henry Cecil was so profitable. At the close of the 1985 season Cauthen enrolled on an alcohol-dependency programme in Cincinnati.

A drinking issue first became apparent to Eddery’s younger daughter when the jockey retired in 2003 at the age of 51. “That’s when I noticed he became dad – and the alcoholic,” said Natasha. “You have the disease and the person. Slowly, you saw it getting worse, and it became really bad when my parents [Eddery and wife Carolyn ] split [in 2009], because I suppose he got more depressed.”

I told him, ‘If you choose drink over health and family, I can’t support that’

Some will contend it was no coincidence that the problem first became evident when Eddery retired from the saddle, initially setting up an owners’ syndicate before establishing his own racing stables near Aylesbury. Though he trained one Group One winner, Hearts Of Fire, he never prospered in the training ranks as he had in the saddle.

On a rare recent public appearance in 2012 on Sky’s Time of Our Lives, in which he reminisced about his career with Willie Carson and Joe Mercer, Eddery seemed at his most energised recalling his routine in the saddle: “A lot of hard work. Day meetings. Evening meetings. Travelling all over the place [albeit frequently in his private plane]. Keeping your weight down. In the sauna every day [to ensure he could do a weight of 8st 3lb].”

When he insisted: “I don’t actually miss it,” it left you wondering. It can’t have been easy to walk away from a 36-year routine, with regular spikes of adrenaline-pumping triumph, probably most notably when, in 1986, the mighty Dancing Brave gave him one of his three Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe victories.

Two years before that television appearance, the six-times champion Kieren Fallon had encouraged Eddery to attempt rehabilitation, according to Natasha. His compatriot, always a greater admirer of Eddery’s composure on the racecourse, had fought his own demons. Drink had been, in part, the consequence of weight issues, but Fallon explained it also gave him confidence, and “allowed me to be comfortable in situations where I wouldn’t otherwise be comfortable”.

Fallon, who once admitted that at one time he was downing a bottle of vodka a day, had sought help from the Aiseiri Treatment Centre in Co Wexford, Ireland, in the winter of 2002, and it was this facility he recommended to Eddery.

Before her father went into rehab, Natasha herself sought help from an addiction counsellor, “because I had so much anger and so much grief”, she explained, adding: “He [Eddery] wanted help and it was going well. Then there was a change five weeks into his programme when he said, ‘I don’t think I’m an alcoholic. I think I just started drinking because my wife left me’.

“I remember feeling like I’d just been punched in the stomach. I thought this has just backtracked on everything. All these years, we’ve suffered with it. I knew then it was over. When he came out, I told him, ‘If you choose drink over health and family, I can’t support that’.

“He looked sad. I separated myself from it because I couldn’t cope with it any more. I felt like I was becoming ill.”

But there were also the warm memories. “[He was] a man of few words, but very loving and funny,” she recalled. “The best things I remember are so simple. He liked mowing the lawn, sunbathing, watching tennis, Sunday roasts. And he was an amazing jockey. You can never take that away.”

A man of extraordinary talent, but with an ordinary man’s fallibility.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies