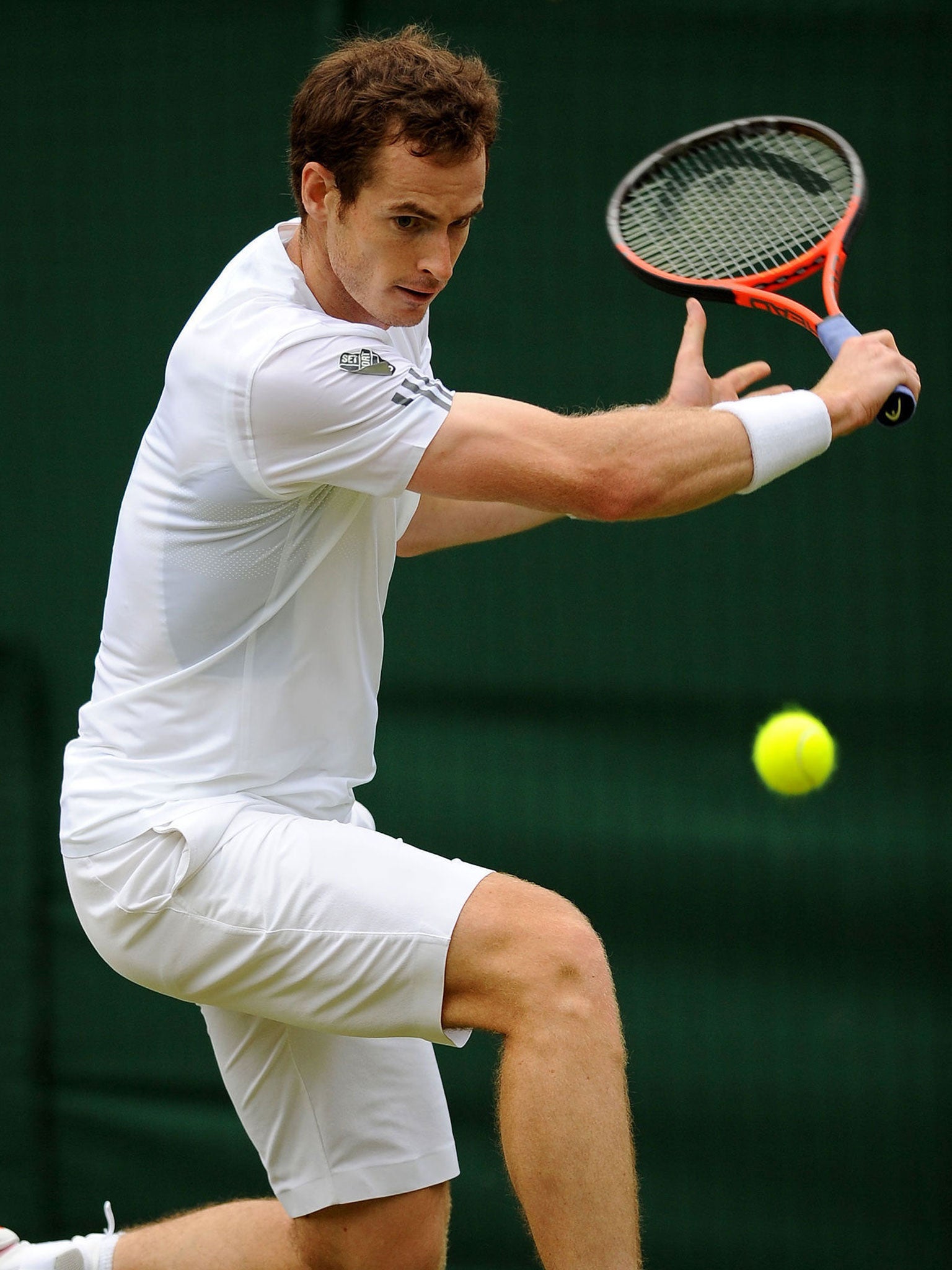

James Lawton: The day that Andy Murray said 'this just isn't good enough'

After his 2011 demolition by Djokovic the Scot knew he had to get serious or stay a nearly man

If it should happen that Andy Murray fails today to win Britain's first Wimbledon men's singles title in 77 years it will surely not be at the cost of another kind of prize he won some time ago.

This one is not inscribed on silver. Nor it is necessarily registered in the cries and the whoops of a patriotic crowd. Rather it is awarded to those sportsmen and women who have clearly met the greatest obligation that can be placed on anyone possessing superior talent. It goes to those who refuse to settle for anything less than being the very best.

It is the badge worn by the supremely ambitious and it is one Murray can wear proudly on the Centre Court when he goes against Novak Djokovic this afternoon.

Murray has already reached out for achievements which many thought beyond him because of a certain brittleness of nature and the timing of his arrival slap bang in the middle of arguably the greatest vein of pure talent his game has known.

But Murray had the nerve and the guts to retrace his steps and see where he was going wrong. He grew strong at potentially broken places.

No doubt he faces a hugely intimidating task today. There have been times these last two weeks when the world's No 1 player has looked unbeatable in the wake of the swift departures of Rafa Nadal and Roger Federer.

Djokovic's ambition has been so plainly ferocious, his execution so clinical and relentless, he has recalled the nickname of the great Belgian cyclist Eddy Merckx. They called Merckx the Cannibal because he devoured his rivals in the mountains. Djokovic has been doing the same to his on the courts, but always there has been one clear counterpoint.

It has been Murray overcoming crisis, producing shots whose authorship any of history's great players would have proudly claimed, laughing when a year or so ago he would have been in a state fit to be tied. Of course, Murray can still get inflamed.

He was enraged on Friday night when officials appeared to have yielded to the pressure of his Polish rival Jerzy Janowicz for the roof to be closed – just when Murray had gained powerful momentum after emerging from a Polish bombardment of 140mph serves and some withering ground strokes.

Murray was angry and said so but plainly he didn't brood. He came back in the artificial light and played with the most authentic conviction. He had performed with similar professionalism two nights earlier while removing the threat presented by the Spaniard Fernando Verdasco, adding more evidence to the argument Murray had indeed looked hard at himself in the mirror in those days before last year's great breakthrough of the Olympic gold medal and the US Open title.

What he did, of course, was something beyond either the will or the inclination of whole generations of male British tennis players and, if we are quite honest, a large slice of the general sports population.

He changed himself and his environment. He enlisted the guidance of the dour old Grand Slam champion Ivan Lendl, who now scrutinises every move made by Murray on the courts to which he brought great talent and unswerving application. Murray didn't settle for being a rich and celebrated nearly man.

He asked for so much more of himself, and the results have been especially evident in this tournament, which might just be claimed for the nation so long after Fred Perry, the combative son of a socialist MP, did it in 1936.

Certainly it is not hard tracing back to the time when Murray knew he had to change. It was in Melbourne two and a half years ago when Murray was not so much beaten in the final of the Australian Open as cut into small pieces.

Djokovic raced to victory in three sets. Murray melted down, competitively, stylistically, emotionally. He yelled at his entourage, he yelled at himself and all the time Djokovic appeared to be occupying another planet.

Murray could be so easily consumed by discouraging circumstances. At Wimbledon two years ago he appeared to have the great Nadal at his mercy, then mis-timed a shot that in his own mind turned from a mishap into a disabling catastrophe.

Today, such a self-inflicted disaster seems so remote it might have happened in another lifetime. After the Melbourne nightmare, he accepted that he needed help, someone to step from outside an admiring circle and deliver some hard judgements.

Lendl was the man and he will deserve great credit if Murray brings down Djokovic today. But then it was Murray who summoned up the help, saw that he had reached a point where he could no longer heal himself.

That was the vital determination – the point where Murray elected himself to the hardest school of thought in sport. If it had a principal spokesman in Britain, the appointment would probably have to go to Sir Nick Faldo, who long before winning six major golf titles declared: "If you want to compete at the highest level, to be the best, you have to remember the really hard work comes when you feel you have reached the top. When I was really competing, I said I would hit a million golf balls just to give myself a chance."

It is something to remember if the formal silverware today goes to the Serb. If Djokovic is the cannibal, no-one can any longer question the appetite of Andy Murray.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies