The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Atlantic Canada: Why does Ben Fogle feel such a connection to the wild fringes of Newfoundland and Labrador

Research for his new book about man's best friend took Ben Fogle to a true wilderness

I have a secret. Not many people know it, but I am half Canadian. Half of my blood flows with moose, canoes and beavers. My father is a fully paid-up, plaid shirt-wearing Canadian who says “eh” after each sentence and proudly displays a maple-leaf flag at home. As a result, as children, my two sisters and I would be packed off to the Canadian lakes each summer for eight weeks of “wilding”. I loved those hazy long summers of fishing, swimming and canoeing. My late grandfather had built a wooden cottage on the shores of a lake in Ontario. He built it by hand which was very much the essence of my time there – wholesome, earthy and simple.

The result of my early experiences in Canada is that Ontario was all I knew. I had heard tales of British Columbia and her vast mountains, and of the icy northern provinces, but they remained abstract regions in a vast country that I half called home. One area in particular had always fascinated me: Newfoundland and Labrador, a huge region comprising the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador that's the same size as Japan. Occasionally I would hear tales of this oceanic world of inlets and fishing ports, but it would take me more than 40 years to visit.

A life-long love of Labrador retrievers would finally result in a visit to Canada's Atlantic coast – specifically Newfoundland and Labrador – to research a book about this popular dog breed in the region which is widely considered to be its place of origin.

The first surprise was getting there – a flight of under five hours from London to the provincial capital, St John's, on Newfoundland, certainly the fastest Atlantic crossing I have ever experienced. St John's is dominated by its harbour, from which dozens of fishing trawlers and offshore supply ships set off into the North Atlantic.

The coastline of Newfoundland and Labrador is more than 18,000 miles long, comprising fjords, inlets, bays, coves and fishing villages that fringe the wild North Atlantic. It is often described as frontier country. During the first half of the 19th century, this was the Promised Land for migrants from Ireland and Scotland who were fleeing economic hardship at home and mostly came to work the rich ocean.

The result is a people set apart from the rest of Canada both geographically and culturally. Their accent can often sound vaguely Irish-Canadian, though when talking to one another they often dip into an incomprehensible patois. My taxi driver reminded me of a Frenchman with his beret, but was a third generation Newfoundlander, he informed me as he drove us to Signal Hill, overlooking the city. This landmark gained its name after receiving the first transatlantic wireless signal from Cornwall by Guglielmo Marconi in 1901.

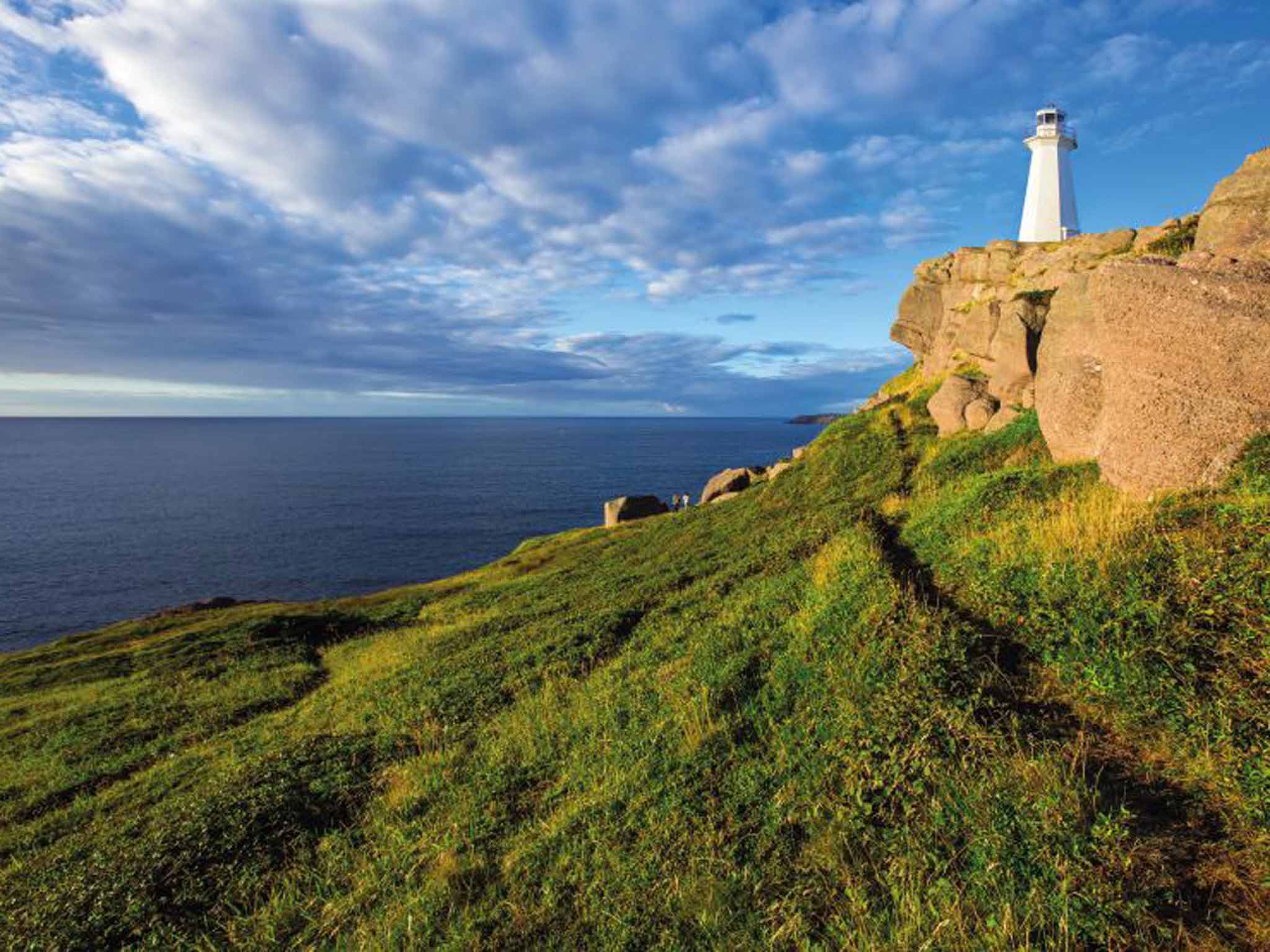

A 25-minute hike south-east from the centre of town transported me to Cape Spear Lighthouse. Like a scene from The Shipping News, the lighthouse is perched atop a dramatic cliff. The view was breathtaking. Huge rolling waves crashed against the rocky foreshore below as flocks of gulls feasted on a passing shoal of fish. As I looked out to sea I pictured the next landfall – Cabo da Roca in Portugal, the most westerly point of mainland Europe, on which I have stood many times, wondering what its North American neighbour looked like. Now I knew.

The mighty lighthouse behind me was a reminder of the treacherous ocean that has claimed many ships and cost many lives. This is a harsh environment. Newfoundland is bigger than Ireland, and for many months of the year the island is buried under 10 feet of snow. Walking along the coastal paths, the vegetation unfolded in shades of crimson, orange and yellow. It was late autumn and soon winter would return.

However, during the summer months, the islanders have a brief respite from the cold, and fishing trawlers make the most of the benign weather. At yet even then, Atlantic Canada is reminded of its Arctic geography as swarms of icebergs descend. Locals make good use of them – with iceberg water, iceberg beer and iceberg vodka. Washed-up shards are collected, to be put to use chilling gin and tonics.

Perhaps the most astonishing industry is the iceberg “movers” – individuals tasked with either blowing up or tugging away mighty icebergs that might be blocking harbours or endangering property. There is even a website, Iceberg Finder, on which “iceberg ambassadors” track the movement of these vast 'bergs, which are more than 10,000 years old and can weigh in excess of 10 million tons.

Ben Fogle's Atlantic Canada

Show all 5Icebergs also bring the polar bears that use them as ocean rafts. The shards sometimes deposit these fearsome predators close to human habitations – a fact which gives rise to another peculiar local expert, the polar bear “relocator”. Sadly, during my visit, there were no signs of icebergs, polar bears or the sperm whales that migrate through these waters – only a vast grey ocean.

A coastal road winds around the fjords of Newfoundland, from Bay Bulls to Witless Bay via countless little fishing villages. Small, multicoloured boat houses and fish shacks sit out over the water on stilts, long piers and docks jutting out into the water, serving as a sad reminder of the region's once-rich fishing heritage.

The cod banks here were legendary. Fisherman once described the cod as being in such abundance that you could walk across the water on them and boats were attracted from all over Europe by the rich bounty. It was Portuguese fishermen who introduced the Labrador dog to the region as a working animal that helped retrieve nets and equipment from the icy waters of the Grand Banks.

The fishermen's catch would be salted and returned to Europe. However, after centuries of over-fishing, the industry collapsed in the early 1990s. A government-imposed cod moratorium was draconian and destroyed many of the communities that relied entirely on the fish. And the Labradors too have long deserted these shores, although I met one friendly Lab and a shaggy Newfoundland posted to welcome arriving cruise-ship passengers.

The region is still very much defined by its fishing past. The food is still dominated by seafood: bacalao (salt cod) is a popular dish, as are cod tongues, doughboys (a deep-fried dumpling), salt fish and brewis, a traditional hard bread eaten with fish. The fishing moratorium still looms large in the community. The huge warehouse building, The Rooms, in central St John's, contains a museum and archive of the rise and fall of the region's fortunes. As I wandered around it, seeing its old wooden fishing boats, I got a real sense of what it must have been like a century ago – a hard place to live.

From the city, I headed south to join part of the 336-mile East Coast Trail, which attracts walkers and hikers to the shores of the Avalon peninsula on which St John's sits. Carolyn, a St John's resident, agreed to be my hiking buddy on the dramatic trail, high above the endless ocean. The footpath follows deep fjords and lush, storm-lashed forests. Fallen trees had been carved into bridges across small streams.

We continued past small, weathered clapboard homes crouching against the prevailing wind atop the cliffs. It was utterly breathtaking. The salty sea air filled my lungs and it felt like we were the only people at the end of the world.

However, the call of the ocean was too strong to stay on land. Fishermen once used simple ocean-going wooden skiffs to row out to the set their nets. I was keen to experience what it would have been like on such a tiny vessel. Happily, some obliging locals volunteered to accompany me out into the North Atlantic aboard one of their tiny boats.

Dwarfed by the mighty supply ships moored up in the harbour of St John's, we rowed out across the bay towards the open ocean. We paddled past dozens of wooden houses, nailed to the side of vertiginous cliffs and beyond the harbour entrance. Our tiny wooden skiff pitched and yawed. We disappeared with each swell, hidden between the mountainous water around us; I felt dwarfed out on the North Atlantic. It was a sobering reminder of how tough life would have been for those early fisherman who came here to seek their fortune – this, I was told, was a calm day in Newfoundland. I could only imagine what it would be like in the middle of winter when the gales set in.

It was a fitting finalé to my first foray into Atlantic Canada. It is a land dominated by its geography and landscape, a place inextricably linked to its past. A true wilderness, just a few hours from home.

Ben Fogle's new book, 'Labrador: The Story of the World's Favourite Dog', is published by William Collins (£8.99)

Getting there

Air Canada (0871 220 1111; aircanada.com) flies from Heathrow to St John’s until 23 October. The route will start again early next summer along with a new route on WestJet (00 800 5381 5696; westjet.com) from Gatwick to St John’s.

More information

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies