Tom Sutcliffe: Mystery appeal of scuffs and smears

The week in culture

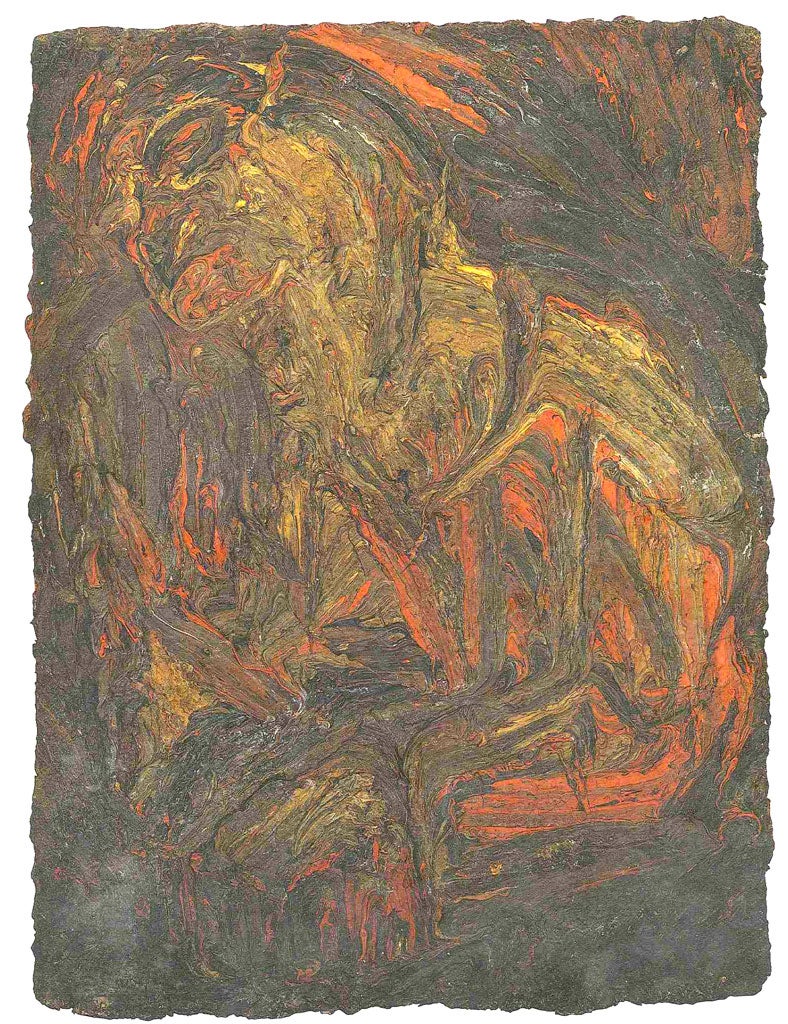

I'm not sure how universal this is going to be as a metaphor but it strikes me as so exact that I'm going to have a go anyway. First, I'd like you to think (if you can) of that odd residue you sometimes get when a coffee cup dries out and you're left with the remnants of espresso-stained milk-skin, a kind of ropy twist of dark material, often with a plasticky shine to it. The colours, in my experience, can range from a glossy chestnut brown to something almost black in colour. Now imagine a portrait-format painting almost entirely composed of this unlovely material, with the occasional admixture of other lighter stool-like colours and the odd swipe of dun red. Actually, I'm not sure you need to imagine the red after all. I'm working from the catalogue for the Haunch of Venison's new show The Mystery of Appearance and in my memory (possibly faulty) the art-work itself is a good deal grimmer and more swarthy than it's reproduction. Anyway, with red or without it, you should now have a reasonable image of Leon Kossoff's Seated Woman No 2, by some stretch the muddiest and most rebarbative painting I've seen this year.

It doesn't look as if it's ageing well either. The paint in the valleys of the deeply worked surface has puckered into those crazed ripples you get when you leave the top off a pot of household paint and the pigment seems to have darkened, so that its harder to see what is more obvious in reproduction – the fugitive presence of the woman of the title, her head canted back and her body hunched. She seems to be leaning forwards a little but it is impossible to say categorically because – with the exception of the region of her head – recognition flickers over the surface of the painting, first lighting on one long smear of paint as a definitive edge and then losing confidence and shifting to another. It's an odd experience looking at it. Not enjoyable exactly or pleasurable in any vanilla kind of way – the painting is just too clotted and gnarled and resistant for that – but compelling even so. It nicely illustrates the Bacon remark that the show takes as its epigraph: "To me, the mystery of painting today is how can appearance be made. I know it can be illustrated, I know it can be photographed. But how can this thing be made so that you catch the mystery of appearance within the mystery of making?"

Actually, in the Kossoff, I'm inclined to think that the mystery of making all but eclipses the mystery of appearance – he's so determined to work away from simple likeness. But his fascination with the contingency of paint, as a stuff that can conceal as well as depict, also finds expression in other paintings in this show that more closely catch Bacon's drift, in particular the way in which he completes his remark: "One knows," he continues, "that by some accidental brushmarks suddenly appearance comes in with a vividness that no accepted way of doing it would have brought about." Or, one might phrase it differently, no teachable way of doing it would have achieved. This show, full of scuffs and smears, of paint that has been allowed to fall where it will, of gluey strands of colour that have looped back under gravity to fall at odd angles across other brush strokes, is partly a celebration of contingency in making art but also a kind of manifesto against the controllable and predictable effect. Even painters like Euan Uglow and William Coldstream, who admit the scaffolding of an academic style into their images (in the grid lines of composition which they leave exposed), only do so to better highlight that moment when "suddenly appearance comes in", like a visitation from another realm. Depiction isn't a knack to be acquired these paintings seem to suggest – it's an evasive miracle that has to be wrestled with and explored and even held at bay from time to time. It's a terrific show, but if you plan to go brace yourself for that Kossoff. It isn't interested in making things easy for the viewer.

Is Tracey Emin such an irresistible draw?

The reaction to Tracey Emin's appointment as Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy resulted in a predictable schism in reaction, between those who think that the organisation has just scored an academic and cultural coup and those who've been making jokes about the imminent appointment of a Professor of Colouring-In. I confess that I'm among the doubters here. Better judges than I have admired the quality of the stitching on the emperor's garment, when it comes to Emin's draughtsmanship, but I just can't see it myself, despite repeated efforts. Perhaps Professor Emin's inaugural lectures will help clear things up. In the meantime, one can't help but admire the way in which she has made herself the go-to-gal when it comes to a certain kind of celebrity arts appointment. Was there ever any doubt that she would be one of the Olympic poster artists? The paper they drew the shortlist up on probably had her name pre-printed at the top. She also helped British Airways as a mentor for their Great Britons programme and she's going to be guest editing the Today programme over Christmas (I'm sure her qualifications to helm one of Britain's flagship current-affairs programmes are just as strong as those that got her the Royal Academy job). I'm beginning to wonder whether there's anything she would turn down. If it was announced that she was to be the Archbishop of Canterbury's special envoy to the Middle East I really wouldn't be at all surprised.

A handle on truly funny theatre

As Graham Linehan pointed out on Twitter, a surprising number of critics took the loose doorknob on the first night of The Ladykillers to be a pre-planned bit of business. It flew off a door on the upper level of the set early in the first act, rolled through the imaginary wall separating the "room" it was in from the rest of the set and was only prevented from heading into the audience by a neat boundary catch by one of the performers. It would have been much less fun, surely, if it had all been rehearsed beforehand. I couldn't entirely work out whether critics were being naive or cynical in giving the credit to the director rather than the fast reflexes of the cast, but I guess it's a kind of cynicism... and I wonder whether it was induced by the way a lot of us were caught out by the "impromptu" bits in One Man, Two Guvnors – particularly the banter with an audience member over a sandwich. It looked like an inspired bit of ad-libbing, but turned out to be a plant (which hasn't stopped it delighting audiences). Perhaps the distinction between these events matters even less than the precise birthplace of polar bear cubs. But I can't shift a paradoxical feeling that the glow we all felt after the doorknob went on tour was more genuinely theatrical than the interruption which had been rehearsed for weeks.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies