Tom Sutcliffe: When collector's items turn to clutter

The week in culture

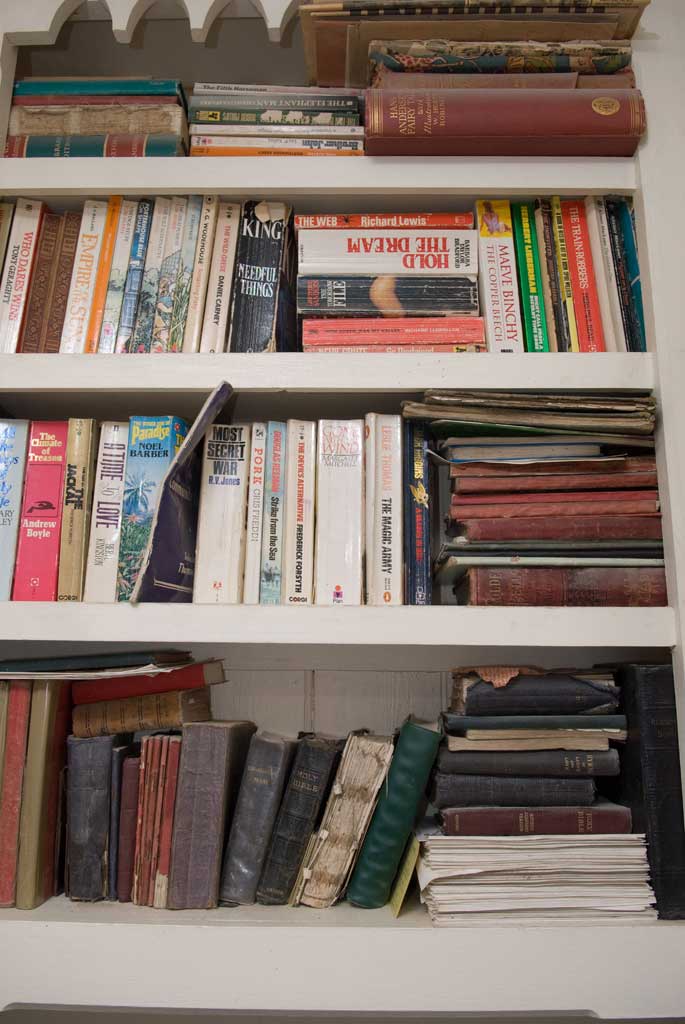

I cleared out my library over Christmas – or rather trimmed and tidied it, nervous that the increasing stacks of books on the floor were hazardously close to tipping its condition from "studiously cluttered" to "Channel 4 hoarder-documentary". A year of unrestrained growth and ill-disciplined browsing had steadily diminished its utility and pleasure. Quite often, I'd know that somewhere in the chaos there was a specific title that would be of use to me, but I wouldn't have the time to hunt it down. And the sense of being surrounded by books was coming to be tinged by a certain paranoia. They didn't neatly furnish the room anymore, a wallpaper of proxy erudition: they were beginning to mass, like the birds behind Tippi Hedren in that famous scene in the Hitchcock movie. It was clear that a cull was overdue.

What I hadn't quite reckoned with was how arbitrary that cull would seem to be, and how it would raise the question of what a private library is actually for anymore. Twenty years ago this wasn't nearly as difficult a question to answer. A library represented a kind of individual statement about literary virtue. It might have its idiosyncratic elements – books kept because of a private or nostalgic association, or a books that spoke to a personal enthusiasm – but the question you would ask yourself in sorting through it would be relatively straightforward: "Will this book be worth reading in 10 or 20 years' time?" If the answer was yes, you kept it. There would be the fairly substantial number of books you'd bought to flatter yourself that you were the kind of person who might one day read such a title (but hadn't quite yet got round to reading). And then, in my case, there would be useful books – non-fiction works that I believed (in the teeth of experience usually) might one day supply a telling fact or a useful inspiration.

This time round though I found that most of those old rationales for whether a book went back on the shelf or into the charity box weren't really functioning properly any more. The arrival of a Kindle and the internet had eaten into what had once been utterly routine judgements. Where once it would have been a no-brainer to keep one's copies of Walter Scott, say, this time round I hesitated. How likely is it, I wondered, that I will reread The Heart of Midlothian just for fun? And should I ever want to find a reference in it for some other reason would its proximity on a shelf be pertinent anyway? I've just looked it up on Google and clicked a link to a Gutenberg edition and it took me 17 seconds. I doubt I could have done it as fast by getting out of my chair, and once I had I certainly wouldn't have had a searchable copy at my fingertips. I could also buy a Kindle copy for 77p that won't need dusting or, by splashing out an extra £1.15 pence, download a collected works that comes bundled with three biographies and a selection of critical responses, including pieces by Hazlitt and Henry James.

The canon, in short, now has less of a claim to physical shelf space than more obscure books. For years now, a copy of Ved Mehta's memoir The Ledge Between the Streams has survived every pruning – some misty romanticism about The New Yorker and India marking it out as a some-day read. This year, finally, it was condemned by sheer bulk alone (I now see that should I ever regret this decision it will cost me at least $63.95 to replace it, which may be good news for Oxfam, I hope). Other books that went may well be irreplaceable, though I console myself with the idea that unread on my shelf is worse than eagerly read by some one else. And wonder about what I kept. Will Robertson Davies's star rise again one day and justify that six inches of precious real estate? Or was it just a temporary reprieve? I really couldn't tell you. What I'm left with now is a tidy study, and a collection of books that makes no sense at all – a mixture of the canonical, the sentimental, the optimistic and simple choice fatigue. And a nagging feeling that a copy of The Ledge Between the Streams will one day be indispensable to me.

The experiment that exposed a cherished myth

I loved the newspaper report about an experiment conducted at an international violin competition in which 21 musicians were asked to conduct a blind-test on six violins, three of which were modern instruments and three of which were by old master makers (two Stradivaris and a Guarneri). The players wore welders' goggles and were handed the instruments unidentified, and under these conditions most of them preferred modern instruments, with one of the Stradivaris coming last. The fabled superiority of such instruments, it seems, is exactly that. A fable. They're excellent (they were up against very good modern violins) but they're not magic, and it seems likely that their reputation rests on a looped set of associations. A great violinist must be able to recognise a greatness that might be inaudible to lesser ears. So the supreme qualities of these instruments are likely to be talked up. And what's interesting is how reluctant they can be to surrender the mystique. Writing in a Guardian blog about the finding, the cellist Steven Isserlis acknowledged the underrated nature of some modern instruments but went on to point out that players themselves might not be in the best position to judge the projection of an instrument. "A famous (and curious) feature of Stradivarius instruments," he wrote, "is that their tone seems to increase with distance." The word "curious" should probably be replaced by "illusory" – but good luck proving it to the connoisseurs.

Memories of a rubbish winter

There's a very funny moment in Phyllida Lloyd's film The Iron Lady in which a relatively youthful Mrs Thatcher walks out of her Whitehall office to find the streets full of rubbish. It's the Winter of Discontent, and British society is coming apart at the seams. Only Mrs Thatcher's gritty determination will stand against this encroaching chaos – clearly something she believed herself but which, at this moment, the film seems to believe too. And the funny bit is the sight of extras, pulling up in cars loaded down with black bin bags and heaving them on to the pavement. The implication is that they've driven all the way into Central London to deposit their rubbish, a level of desperation which doesn't tally with my own memories of that period. I took it as a classic example of the way that cinema caricatures the past, exaggerating and compressing to create a cartoon history. Then I looked online at some images of that grim winter and realised that, while the film overplayed the grot, my memory had underplayed it. I'd had a kind of proxy media memory of a mountain of rubbish in Leicester Square, but no direct personal memory of what you would have thought would have been a fairly unforgettable sight. In truth, I can't recall what I did with my rubbish, or even whether I was inconvenienced. At the time it was just a background detail. It only became an emblem later.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies