The American hysteria that led to CIA torture

Out of America: Amid the justifiable recriminations, it is too easy to forget that 3,000 people were killed in the US in one day

It has been a very bad week for American exceptionalism – for the country that likes to see itself as the shining city on a hill, a moral beacon for the rest of fallen mankind. Hypocrisy has been the word on every lip: how could the US lecture the rest of the world about human rights and the virtues of democracy even as, according to the chilling report of the Senate intelligence committee, it perpetrated unspeakable torture on suspects held in the "war on terror", some of whom were guilty of nothing more than being in the wrong place at the wrong time?

But the charge applies not only to the United States in its behaviour on the world stage. It might also be levelled at some of those on Capitol Hill who now fulminate so loudly at the practices of the CIA. It's pretty clear they were broadly informed at the time about the "enhanced interrogation techniques", or EITs, being employed during the three years after 11 September 2001. But they raised no objection. Then again, who's to blame them?

Amid the outrage, it's important to remember the sheer fear abroad in the land in the aftermath of 9/11. Almost 3,000 people had been killed that day in New York and Washington, by enemy attacks on the US mainland unprecedented in history, against the symbols of US financial and military power by a terrorist group that the country's security services knew next to nothing about.

The one thing they were sure of was that, having struck so devastatingly once, al-Qaeda would do so again. Those fears were further fuelled by the discovery of crude diagrams suggesting that Osama bin Laden's organisation was after nuclear weapons as well. Then came the mysterious anthrax attacks. America was terrified. The politicians merely reflected the national mood.

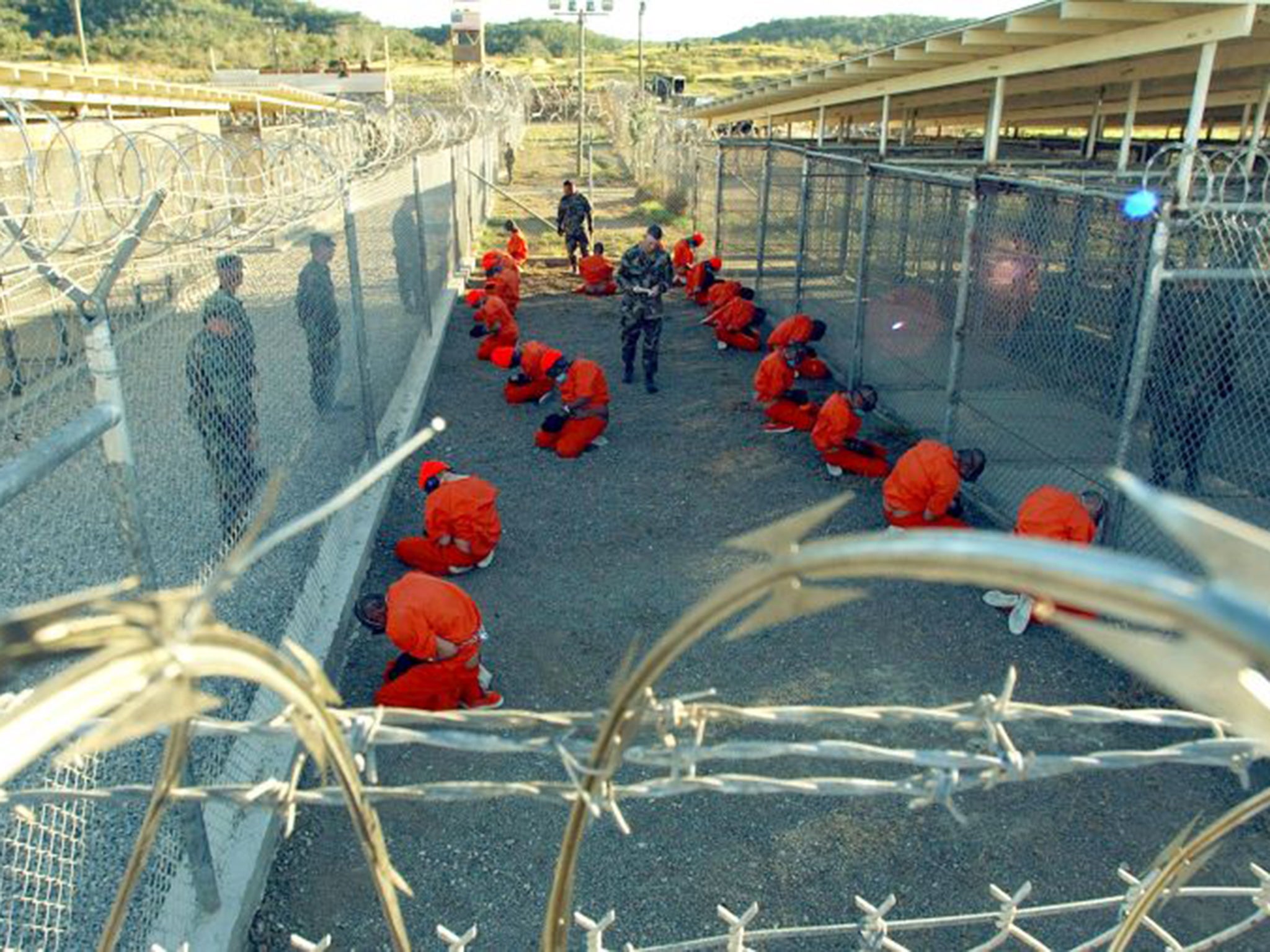

When the first shipment of foreign detainees was flown, shackled to their seats, to Guantanamo Bay in January 2002, even the normally restrained General Richard Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the most senior US uniformed military officer, described them as "people that would gnaw through hydraulic lines in the back of a C-17 to bring it down".

A poll at the time would surely have found 80 per cent support for the notion that anyone remotely connected with al-Qaeda deserved everything they got. Or as Dick Cheney, unrepentant defender of EITs and everyone's favourite villain, said of the torture of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, a prime architect of 9/11, "What are we supposed to do – kiss him on both cheeks and say 'please, please tell us what you know?' Of course not!"

And back in 2002, "Amen to that" was the overwhelming national response to such sentiments. "This is not America. This is not who we are," Angus King, an independent Senator from Maine says of the new report. But a dozen years ago, it was exactly what America was. And it is, to an extent, what America has always been.

The country's original sin, slavery, was underpinned by systematic brutality and torture. Torture was used in the Vietnam war, while the CIA at the very least abetted torture by the rightwing regimes the US supported in South and Central America during the 1970s and 1980s. To this day, US justice abounds with institutionalised excess: forced confessions, a penal system that imprisons more people per head of the population than any other on earth and the widespread use of solitary confinement, a practice widely classified as psychological torture. In 1983, a Texas sheriff and his deputies were even convicted of waterboarding suspects.

But none of this quite explains the response to 9/11. You might argue that the hysteria was exaggerated, that the reaction wouldn't have been as panic-stricken in other democracies such as Israel, France or Britain, more used to terrorism and direct attacks. But the last two didn't suffer peacetime attacks on Paris or London that killed 3,000 people at a stroke as part of a protracted guerilla war.

Invariably, that kind of conflict brings out the worst on both sides; take the reciprocal atrocities in the Algerian war of independence against France or Britain's use of torture in Kenya in the 1950s, for which an initial agreement was reached in 2013 to pay compensation to the victims. In that sense the US is unexceptional: neither better or worse than anyone else.

America being America, of course, the law was employed, or rather invented, to justify such conduct. In this undeclared war the terrorists were deemed "unlawful combatants", not entitled to the protection of the Geneva conventions (even though the administration mendaciously asserted they were being treated as if they were).

As for torture, Justice Department lawyers came up with a definition that it was constituted only by actions "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function or even death".

Tell that to the detainees who were banged against walls, kept sleepless for days or, in at least one instance, left to freeze to death. Apropos of torture, one is reminded of former Supreme Court Justice Stewart Potter's remark about hardcore pornography. He could not, he said, "intelligibly" define it "but I know it when I see it".

The Senate report leaves little doubt that senior American officials, including President George W Bush, came to know about the EIT programme. But they preferred not to see the appalling details. In other words, they behaved as their counterparts would have behaved in other countries, keeping the sordid truth at one remove to preserve their "deniability".

So much, then, for American exceptionalism – except in one vital regard. The report may be partisan, authored by the Democratic majority on the committee without a single Republican, but it came out. What other country would wash its dirtiest laundry so publicly? For that, at least, we must be thankful.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies