The Bank of England thinks the long-term jobless are out of the labour market. They are wrong

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee has zero evidence to support this idea

For the first time in four months I hobbled out of New Hampshire and went to the Windy City of Chicago where I had dinner with two great golfers who were playing in a PGA Champions Tour tournament. Brad Faxon is probably the greatest putter ever and Michael Allen won the Scottish Open on the King’s course at Gleneagles in 1989. Michael played well over the next two days and managed to tie for second place, On the last hole he hit his second shot to six inches and only lost when Tom Lehman holed a birdie putt on the last from around 12 feet. It’s tough at the top.

I arrived back home in time to watch Mark “I am forever blowing bubbles” Carney’s appearance at the Treasury Select Committee to explain why he had made such a fist of it with his Mansion House speech, where he raised market expectations of a rate rise in 2014. Apparently he didn’t really mean to do this, although why was never exactly clear but it had something to do with “uncertainty”.

This had had the effect of raising the pound to over $1.70 as well as the cost of borrowing, which in itself made the chances of an early rate rise less likely. Mr Carney made it clear that he was watching the data and in particular wage growth, which had, to his surprise, disappointed on the downside. As readers of this column well know, that is not exactly a big surprise to this labour economist.

The Thursday announcements from the worthless Financial Policy Committee that they would introduce some non-binding measures that would have no impact at all on the already surging house price bubble added to my view that Mr Carney is a closet West Ham supporter. The restrictions on lending will not affect current lending, so that’s fine then. All words and no action as the housing bubble continues to inflate. I see no ships!

As I noted above, Mr Carney apparently has been expecting a big upsurge in real wage growth starting in the second half of the year which shows no sign of happening. This claim is based on what Mervyn King used to like to call “judgements”. That is to say, they just make it up as they go along.

Let me explain. Wages are likely to rise when the economy approaches full-employment and not before then. Every student of economics is taught that full-employment doesn’t mean that there are no unemployed people as people will always be changing jobs in a capitalist economy. But as we approach full employment the only way for employers to get workers is to take them from other firms by offering higher wages.

The problem is that it’s largely guesswork where that point is; my view is that it is well south of 5 per cent and probably closer to 4 per cent. We are a long way away from that point with an unemployment rate of 6.6 per cent. But there is actually even more slack than that.

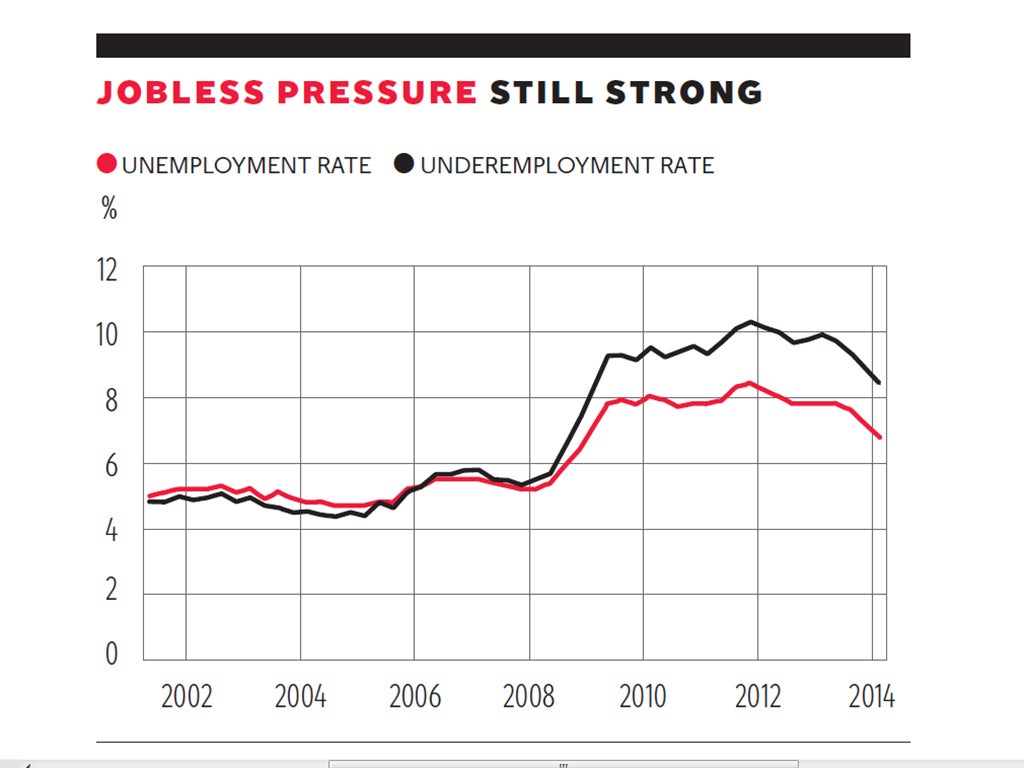

David Bell and I have identified that over and above the unemployment rate there is a large amount of underemployment that makes for even more labour market slack. Each quarter the Work Foundation publishes our underemployment index and the latest is out this week and is plotted in the first figure. It is calculated by using the same data the ONS uses to calculate the unemployment rate – the Labour Force Survey – where workers were asked if they would like more or less hours at the going wage. It turns out that presently on average workers are prepared to take a lot more hours without adding to wage pressure. We then calculated how much unemployment equivalents that amounts to. The chart illustrates that between 2000 and 2008 there was no underemployment but since then the two series separated sharply. Our latest seasonally adjusted estimate for Q12014 shows the unemployment rate is 6.8 per cent compared with an underemployment rate of 8.4 per cent.

The reason the MPC thinks there is going to be lots of wage pressure and soon is because they have decided to bring hand waving back into fashion and, by hand, lower the level of labour market slack to make the UK quite close to full-employment. In my view these downward adjustments are in error. Firstly, despite the fact that the MPC recognises there has been a rapid growth in underemployment, in their forecasts they decided they will just ignore half of the underemployment, or 0.9 per cent. This is surprising given it is clear that in the period 2001-2008 the underemployment and unemployment rates were broadly equal.

Secondly, the MPC also decided, with a stroke of their collective pen, that because just over a third of the unemployed have been out of work for at least a year many of those job-seekers are not really unemployed at all and that the the unemployment rate is accordingly lower. The MPC said in its May Inflation Report that this “reflects a judgement that people who have been unemployed for some time put less downward pressure on wages because they are less likely to find jobs”. This argument has zero basis in evidence.

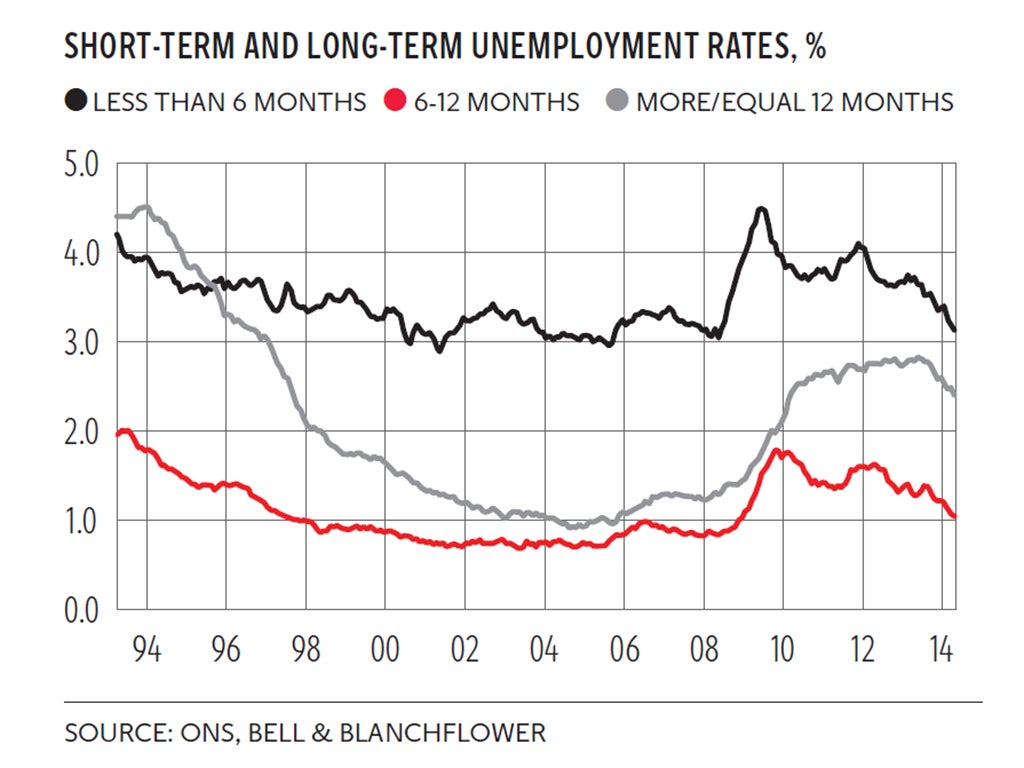

The MPC has absolutely no evidence at all that the long-term unemployed are different from the short-term unemployed. Indeed, the second graph suggests that simply is not the case. It plots short-term and long-term unemployment rates (they add together to make the overall unemployment rate) which move together and if anything the long-term rate is more cyclically volatile.

In 1990 I published a paper with my co-author Andrew Oswald* on exactly this issue and concluded “the British evidence does not support the view that long-term unemployment is an important element in the wage determination process”. Indeed, I asked the Bank of England if they had conducted any work on this since then or knew of any empirical evidence for the UK to support their adjustment. In response, a spokesman told me that: “We have not published any empirical work on this, and have no plan to, that I am aware of”. No wonder they are in wage trouble.

The proof of the pudding of course is in the eating. Wage growth continues to disappoint on the downside. The MPC is just making stuff up (and badly) as they go along.

Blanchflower and Oswald (1990), “The wage curve”, Scandinavian Journal of Economics

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies