The death of Studio Ghibli was inevitable — but this might not be the end

What always made the studio so unique was its refusal to compromise

Hayao Miyazaki saw it coming.

Cameras trailed the great director as he honed his swansong movie, The Wind Rises, before its release in September last year. In the resulting documentary — titled The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness — a voice from behind the camera asks Miyazaki if he’s worried about what will happen, to the studio he built once he retires.

The 73-year-old replies with a smile: “The future is clear. It’s going to fall apart.” He emits one of the enigmatic chuckles with which he generously uses to punctuate his speech. “It’s inevitable.”

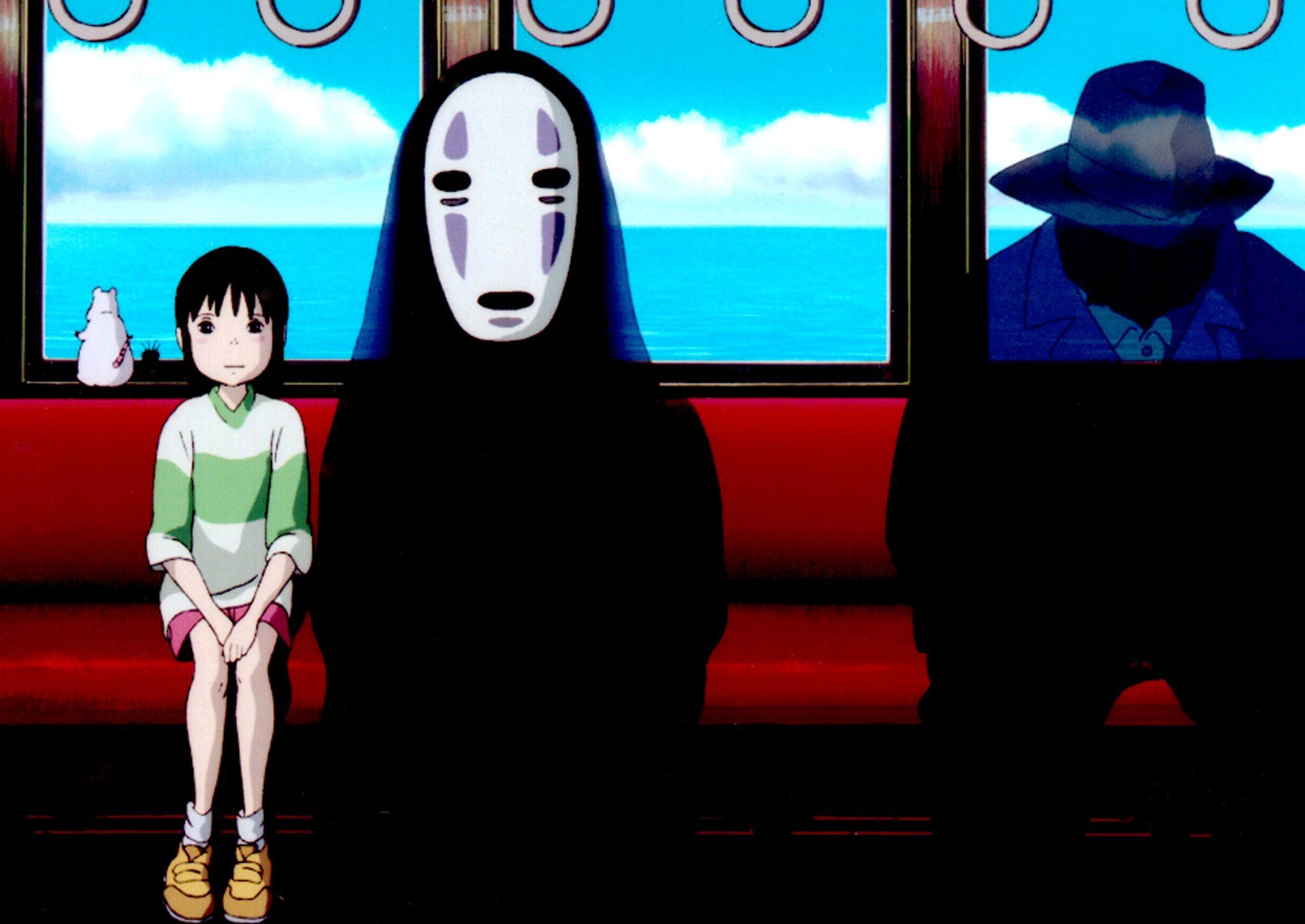

A year on, his prediction looks dead right. Yesterday’s announcement that Studio Ghibli will halt production after 29 years initially led fans to fear the worst. Blogs, then newspapers, buzzed with reports claiming the studio — responsible for bringing Japanese animation to global audiences with modern classics such as Princess Mononoke, My Neighbor Totoro and the Oscar-winning Spirited Away — would close immediately.

Without Miyazaki’s box office draw, the company’s earnings are expected to tumble. Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises brought in almost $120m, while the current non-Miyazaki-helmed Ghibli release, When Marnie Was There, has taken just a third of that number.

In interviews as far back as 2010, Miyazaki had revealed Ghibli’s back-up plan: slashing the 300-strong team to five staff charged with managing existing intellectual properties.

Fans have already begun trading optimistic notices that today’s stop would not mean the end of production. On Reddit’s Ghibli fan domain, a post promises (albeit with scant evidence) “in reality their (sic) is nothing to worry about.”

The studio was left to reassure fans that it was adapting, not closing – calling the restructuring “housecleaning.” But few doubt that big changes will be made to the studio's uncompromising approach.

The painstaking production of hand-drawn animation is not cheap, and Ghibli’s unusual business model has been weighing them down. Where other studios survive on skeleton crews — bulked out by temporary animators during active production — Ghibli’s expansive family of full-time employees eat up cash, even while inactive. Variety predicts salaries now account for $20 million in costs.

In the cinema, young audiences’ enthusiasm has been tested by the studio’s recent taste for sombre subject matter. Miyazaki’s latest covers the disastrous Kanto Earthquake of 1923, a tuberculosis epidemic, and Japan’s entry into the Second World War — a sharp turn away from the family-friendly fantasy adventure genre that has provided the studio’s biggest windfalls.

These irregularities were swallowed while Miyazaki’s ideas printed money (the director still holds still holds four slots in Japan’s Top 10 highest grossing films of all time.) But, now, all eyes are on the studio’s one big disappointment: its failure to nurture a successor capable of sustaining this momentum.

For the studio to win back the creative independence it had under Miyazaki, it’s going to need box office hits, and that will mean changes, from the company’s make-up to the films it makes.

Carelessness, greed, and intolerance of new ideas are not traits Ghibli can afford to exhibit, and rediscovering its youthful excitement may mean drastic reinvention for the studio.

A 3D CGI Ghibli would still be unthinkable – surely — and for some fans, any such departure would signal the final death of the studio they loved. But Miyazaki himself was ready to acknowledge innovations such as CGI allow animators to surpass the capabilities of the human hand, meaning that a second golden age of Ghibli might look very different from the first.

For Miyazaki, there’s no point in worrying about the studio’s legacy or what the future will bring. In the documentary, just seconds after the bearded director makes his grim prediction, we see him wearing shades and feeling philosophical.

“’Ghibli’ is just a random name I got from an airplane,” he says, putting one of his long, white cigarettes to his lips.

“It’s only a name.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies