Elephant Campaign: The Samburu know the land and its animals better than anyone: ‘The elephant is an elder to us – it is taboo to hurt one’

The Samburu tribe once lived side-by-side with elephants in Kenya’s remote Milgis region. Now they have joined the battle for protection

“The first man said the elephant is like us, like our brother, and we have to live together, not hunt elephant,” the tribesman told me. “That’s what we say we were told at the beginning. That’s what we still believe. The elephant has always been, and will always be, special to us. This is why we protect it now.”

We were deep in the bush of northern Kenya, in an area called the Milgis, where the ground is dusty and the only plants are hardy bushes clinging to hillsides. When rains do come, fast-raging rivers briefly flow, but when they don’t, like now, the beds dry up and turn into vast sand dunes that wind their way across the landscape. It was on one of these that we had struck camp.

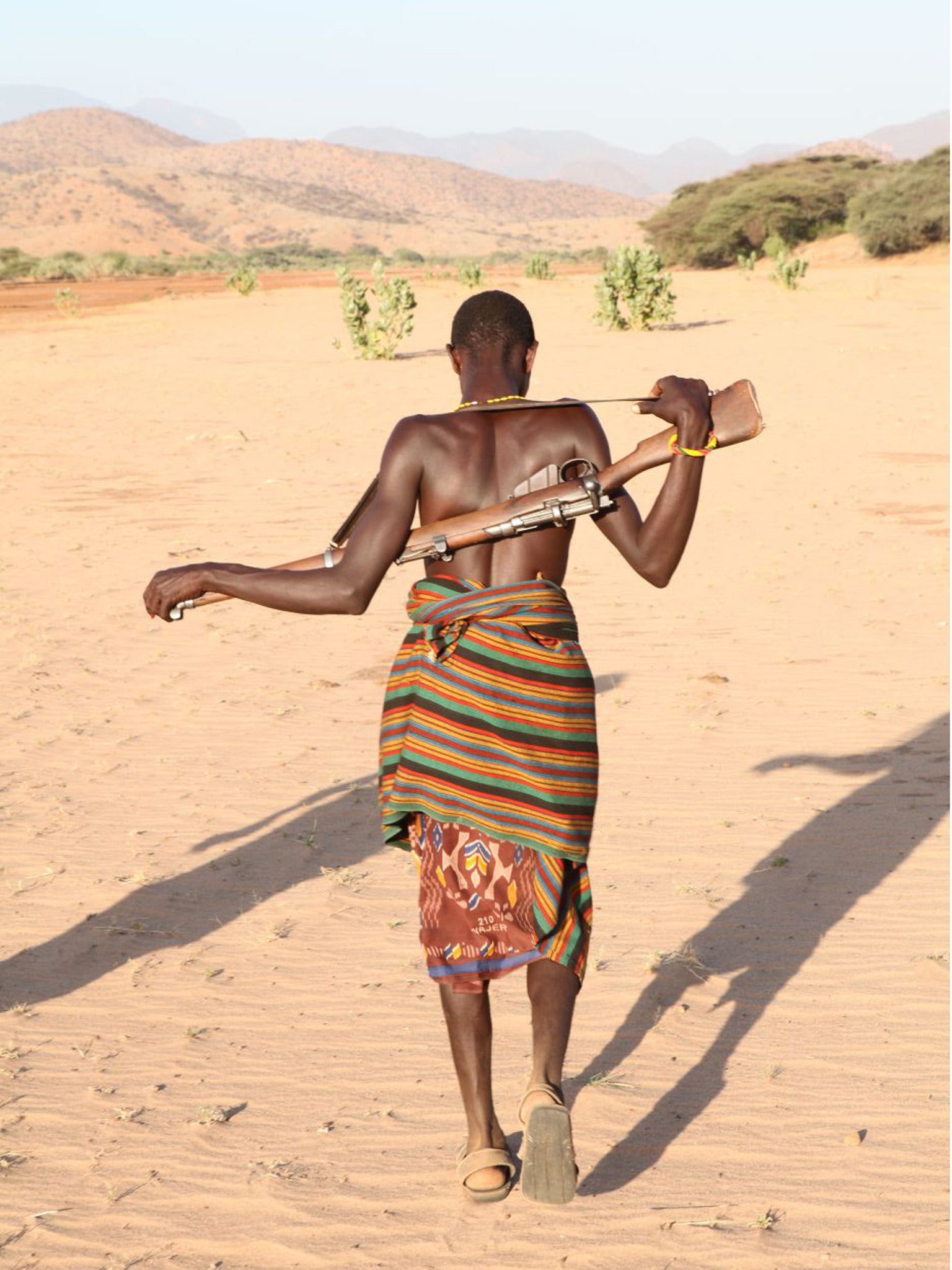

Few Westerners come here. This is the land of the Samburu, one of Africa’s oldest and most exotic tribes. Partly it is their appearance that makes them so special: the warriors decorate their faces and upper bodies with intricate patterns, emphasising their eyes and arranging their hair into elaborate plaits. Multi-coloured beads hang from their necks and arms, while the shukkas around their waists are often set off by a bright white sash.

But it would be wrong to think their dainty appearance indicates weakness. The Samburu have a fearsome reputation as warriors and hunters. From when they are young boys, they are trained to fight with sticks. After puberty, the young men are sent off to live for years in the wilderness.

They know the land and the animals who live there better than anyone – which is why they have proved so important to saving this wildlife from the poachers hunting exotic animals, particularly elephants, in unprecedented numbers.

I had travelled to the Milgis to spend time with them as a remarkable project has been implemented on their tribal land that has restored animal numbers previously hunted almost to annihilation. In the past few months, The Independent has been exposing how serious is the threat posed by the global poaching crisis. Here, I had been told, can be found hope that it could be defeated.

The Samburu made our camp and lit a fire on which we cooked breakfast. As food was prepared, their leader, Moses Lesoloyia, 43, explained why the conservation struggle was not just some Western concept but a principle anchored deep in local custom. “We say the elephant is like an elder to us,” he said, “so it is a taboo to hurt them. If we see one has died we pay respect to it. In our culture we leave small gifts, like beads or milk or green branches, on people’s graves. If we see the remains of an elephant, we do the same as a sign of honour.”

Samburu tradition says that humans and elephants used to live side-by-side in the same villages. The elephants used to help the women, doing jobs like gathering firewood for their homes. It was an argument – apparently prompted by one of the women complaining that the pieces of wood brought were not big enough – that supposedly caused the elephants to leave. But even after that they were considered fellow tribesmen.

The Samburu are divided into clans and one of the most important is the elephant clan, known as the Lukumai. Whenever a member of the clan meets an elephant, custom requires the clansman to throw dirt in the direction of the elephant to see if it is OK for them to pass. Only when the elephant kicks some dirt back is it safe to move on.

It is an ethnographic tradition that has created the ideal foundation for conservation. A decade ago there were no elephants left in the Milgis; all had been poached by hunters coming in from outside. Now there are hundreds and the river bed on which we sat was criss-crossed with elephant prints, including the dainty marks of freshly born young.

The reason why is the establishment of the Samburu community-based conservation project. It gave the Samburu, in partnership with the Kenya Wildlife Service, protection over the animals in their area. They now act as an early warning network for intrusions. Moreover, they are rewarded for their work, which provides much-needed financial assistance.

Mr Lesoloyia detailed how even the youngest members of the tribe have been recruited to the cause, not least by the introduction of special conservation classes in schools. The previous week, two poachers had been caught by the wildlife service after a tip-off from two young goat-herders. The boys helped to track them for days until the rangers arrived, and were rewarded with new goats for their flock.

Seeing what has been achieved with the Samburu was a welcome discovery. Before and after Christmas I spent weeks in East Africa witnessing the devastation poaching has wrought. With an elephant now being killed in Africa every 20 minutes, and with South African officials revealing that 1,007 rhino were killed last year when in 2007 it was just 17, the struggle can at times seem hopeless.

But there are success stories which show that, if the right provisions are put in place and the support of local communities enlisted, the poachers can be defeated.

As well as the Samburu project, I saw ranger teams who go toe-to-toe with elephant-hunters, often in brutal firefights. I discovered programmes to educate the judiciary and police on how to tackle the problem and stamp down on the corruption the criminal gangs foster to smuggle illegal wildlife parts out of Africa.

Perhaps most important of all, I learnt of vast, million-dollar initiatives to educate those who buy animal parts, particularly in Asia, on the true cost of their purchases. Astonishingly, 70 per cent of those surveyed in China did not realise ivory came from dead elephants. It is in correcting these misconceptions, and thereby stemming demand, that the fight against poaching will truly be won.

On the 12th and 13th of this month, the world is gathering in London to address the poaching crisis. Fifty leaders, including from across Africa as well as the Asian states where so many of these items are bought, will be attending a conference hosted by David Cameron and supported by the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge.

It is a precious opportunity to stop this trade before it is too late. If nothing is done now, some of the world’s most iconic species are doomed. Wild elephants could be wiped out within 20 years and rhino so reduced in numbers that they can no longer sustain an adequate gene pool.

Over the past few weeks, Independent readers have responded with more generosity than we had ever hoped possible in raising hundreds of thousands of pounds for anti-poaching projects. It has made it the most successful Christmas campaign in this newspaper’s history. Now we hope to use that same commitment to help ensure the opportunity offered by the London conference is not lost.

We are demanding that real action is taken by those attending, not just the wishy-washy pledges that can too easily emerge from such inter-state events. Concrete provisions must be agreed to stop the trade. To ensure that, we are demanding that those present must agree to:

* Provide better training and resources to rangers to protect elephants and other species;

* Stop demand by educating consumers, particularly in Asia, about the catastrophic impact that buying illegal animal parts has on both wildlife and local communities;

* Stamp down on corruption and implement adequate laws and legal punishments for those involved in the illegal wildlife trade;

* Uphold the existing ban on the global trade in ivory;

* Aid communities in poaching hotspots to develop sustainable livelihoods and provide incentives to protect their wildlife.

In the coming weeks, as our wildlife campaign enters its final days, we will be focusing in our papers and on our website on the importance of each of these pledges. Please help us to ensure these steps are taken by visiting our website and signing our petition demanding real action.

Spread the word. Encourage your friends and family. Let us together send a message to the Prime Minister and the other conference attendees that these crucial commitments must be agreed before it is too late.

As I saw in the Milgis, if we take the right action and safe havens are created, animals will come back and thrive. There is still hope. But time is running out. If these magnificent animals are to have a chance of survival, it is up to all of us to do what we can to protect them, and do it now.

Evgeny Lebedev is the owner of the ‘Independent’ titles and the ‘London Evening Standard’. Follow him on Twitter: @mrevgenylebedev

To sign The Independent’s Save the Wildlife petition and learn how to get involved in our elephant appeal visit: independent.co.uk/voices/campaigns/elephant-campaign/

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies