Everyone's a winner on the level playing fields of sport

Out of America: Baseball and hockey don't follow the stereotype of rampant US capitalism

Remember all the fuss when the American neo-conservative thinker Robert Kagan came up with his "Americans are from Mars and Europeans are from Venus" line?

That was back in 2002, when George W Bush was preparing to invade Iraq, to the horror of most of the Old Continent. But it encapsulated broader assumptions about fundamental trans-Atlantic differences, between a US that practised a pure and virile capitalism built on individual initiative and the survival of the fittest, and a cossetted and ever more sclerotic Europe, where governments and unions ran things, averse not only to war but to anything that smacked of confrontation and risk-taking.

This, in any case, was how many people here viewed Europe. And they still do. During the recent election, Mitt Romney held out "socialist" Europe as a nightmare vision of America after four more years of Obama. And the unending euro crisis hasn't helped either, cementing the image of a continent that lacks the strength and willpower to haul itself out of the mire.

Americans get far more agitated about the role and power of government than Europeans, while social safety nets are fewer (though you might not think so, given the current hullabaloo about the modest changes to government-run Social Security and Medicare floated as part of a package to prevent the US sliding over the "fiscal cliff").

As for unions, their role may be declining in Europe, but nowhere near as rapidly as here. US union membership is at its lowest in 70 years. And in 2009 – even with Democrats controlling the White House and the whole of Congress – a proposal to make it easier for workers to join unions, and to penalise companies that discriminated against them for doing so, died a death on Capitol Hill. But one unexpected area has turned out to be the exception proving Kagan's rule. I refer to top-level professional sport.

When it comes to its common faith of football, Europe operates by unadulterated Darwinism. Money alone rules. The main leagues are dominated by the same handful of clubs (the richest) and the price of failure is inevitable: for teams, relegation; for managers, the sack (as in Di Matteo, Roberto).

Not so in America. Here the top leagues operate as cosy cartels. Promotion and relegation do not exist. Instead, elaborate systems of revenue sharing, in some cases reinforced by salary caps, have been installed. A draft mechanism further evens out disparities by sending the best new players to the worst teams – which is one reason why the last 12 World Series in baseball have been won by nine different franchises. And finally, if there's one place where unions thrive, it's in major league sport.

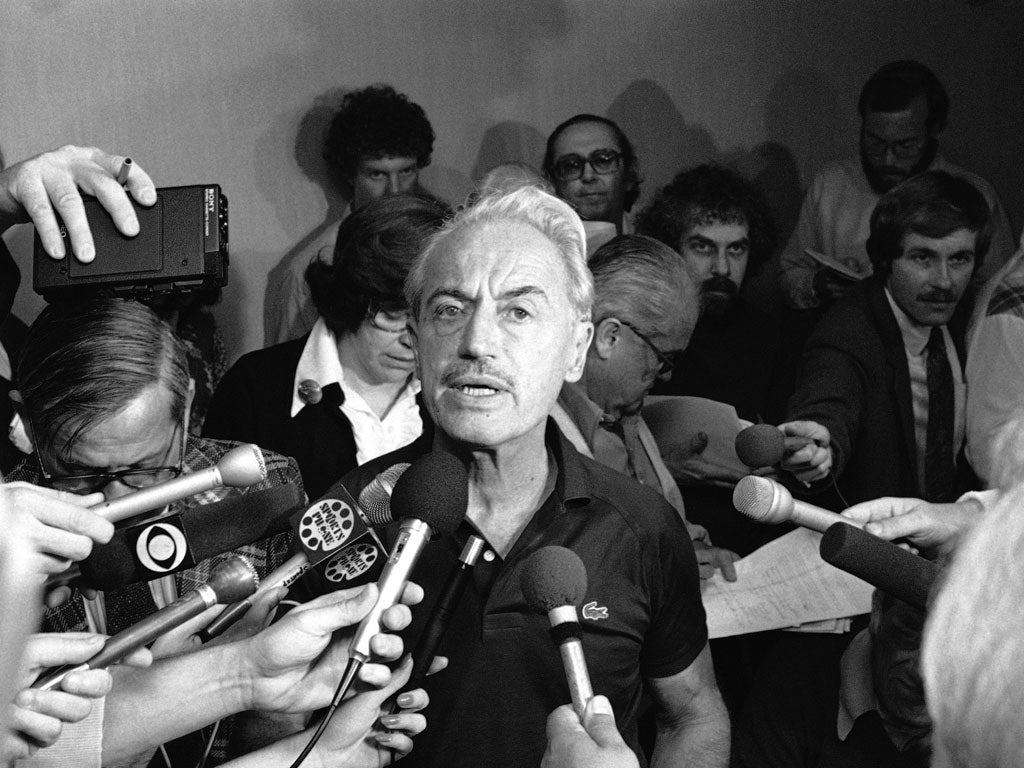

Two not-quite-unrelated events last week were reminders of that truth. The first was the death of Marvin Miller. You've probably never heard of him, but when it comes to baseball he's of Babe Ruth importance. Quietly spoken and sporting a matinée-idol moustache, Miller resembled an old-school diplomat rather than a baseball man. He never played the game seriously. But he was a brilliant and ruthless negotiator who headed the Major League Baseball Players Association (or union) between 1966 and 1982.

When he arrived, the players were "among the most exploited workers in America", he wrote in his memoirs: woefully underpaid and with a wretched pension scheme. Even after their contracts had expired, they were bound to their teams by a "reserve clause", like the "reserve-and-transfer" rule that prevailed in English football until the 1960s. When Miller left, the reserve clause was history, replaced by today's system of free agency. This has helped boost the salary of the average major leaguer to $3m (£1.9m) a year. It also anticipated the 1995 Bosman ruling that transformed player-club relations in European football.

The baseball owners considered him little better than a communist, but he had the better of them every time. Their small-minded revenge was to see to it that Miller was never in his lifetime admitted to baseball's hallowed Hall of Fame, even though he was one of the half-dozen people in baseball's history who truly transformed the sport. In death, that injustice may at last be corrected.

The second piece of news was of further deadlock in the National Hockey League labour contract talks, 75 days after an owners' lock-out of the players. A third of this season's scheduled games have already been cancelled. Almost unbelievably, hockey (the ice variety, that is) could soon be facing a second lost season within eight years – despite a boom in spectators and TV ratings. Imagine that happening to the Premier League, Serie A or La Liga; national disaster would be declared.

A mixture of stubborn owners who, unlike most of their European counterparts, run their clubs as a money-making business, and strong player unions have proved a constant recipe for trouble. Miller presided over baseball stoppages that disrupted four seasons. Basketball and American football have had labour disputes too, but none to rival those in hockey, whose union is led by a gimlet-eyed lawyer called Donald Fehr. It was he who succeeded Miller at the baseball players' association and was in charge during the sport's last big stoppage, which wiped out the 1994 World Series.

It helps that these particular union members are mostly rich beyond ordinary dreams. But one consideration might give Robert Kagan's most ardent Martian pause for thought. Under the system Miller shepherded into existence, everyone has benefited: the players, obviously, but also the fans and even the owners. They're in it for money, and they're making more of it than ever.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies