Go Set a Watchman: Harper Lee’s new novel is more than just a literary event

Celebrations are in place for the long awaited sequel to her Mockingbird classic, but did Lee actually consent to its publication?

Fasten your dungarees. Practice your Southern drawl. Fire up the Cajun barbecue and hurry down to your local bookshop. 'Go Set a Watchman', the publishing event of the year – nay, decade – is upon us, and it can only mean one thing. That most communal, least literary of events: the midnight launch party. Yay!

At the Dorchester Waterstones, planning for the 14 July release is already at an advanced stage. A “tequila mocking bird cocktail party” awaits, as does a quiz, fancy dress (Scout-style overalls encouraged), and several buckets of Alabama-style fried chicken. The choice of food, among other things, may prove contentious. Harper Lee mentions over 50 foodstuffs in 'To Kill a Mockingbird', the 1960 sister novel to 'Watchman', and avid fans may have hoped for a more recherché choice: an alternatives menu might have included cornbread, scuppernongs (large Southern style grapes), and cats and squirrels (the imagined diet of Boo Radley).

Meanwhile, screenings of the 1962 adaptation of 'To Kill a Mockingbird' are pencilled in at independent bookshops from London to Hove to Shrewsbury. And elsewhere Waterstones and Penguin Random House have even managed to produce an “exclusive” edition of 'Mockingbird', based on the original 1960 publication (I examined the new copy yesterday – it has a different cover).

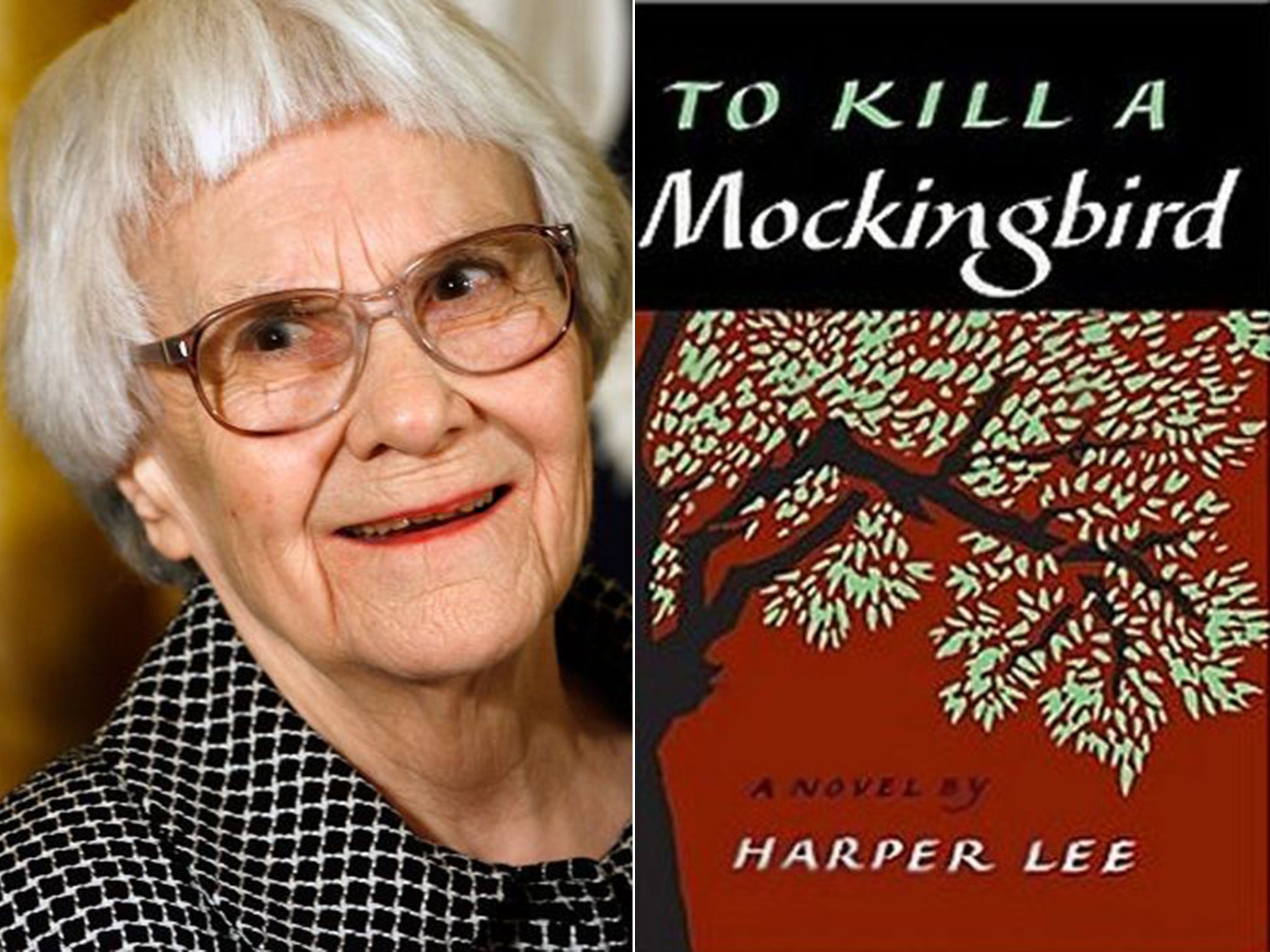

All of which, of course, is grist to the mill of marketing this most hotly-awaited book. But amid the screenings, the releases, the re-releases, and the opening parties there is of course one figure conspicuous by her absence – the author. Eighty nine-year-old Harper Lee, less a mockingbird, more these days an endangered Melodious Warbler – the rarest of birds with the sweetest of unheard voices – will not be attending. Waterstones may as well have invited Boo Radley.

One wonders, of course, what Lee – now almost blind and deaf after a stroke in 2007 – can or does make of this all. One treatment her new publication will receive is having 'Go Set a Watchman' publicly “speed read” at the Forum Books shop in Corbridge, Northumberland. Anne Jones, a world champion speed reader, will try to read the text in under 30 minutes to a live audience – a stimulating spectacle, no doubt.

Lee, meanwhile, will see out the celebrations from her care home in Monroeville, Alabama – the assisted living facility which has been her home for the last eight years. It is unclear how much she welcomes the release. Indeed, the genesis of the novel – the story of the story, and its complicated publication history – continues to fascinate would-be readers.

A report from the New York Times says the manuscript of 'Watchman' (actually written before 'Mockingbird'), was rediscovered in 2011, and subsequently buried again at the request of Lee and her then lawyer and sister Alice Lee. But Lee’s new lawyer, Tonja B Carter (Alice Lee died last year at the age of 103) claims to have discovered the manuscript of Watchman in a safe deposit box as recently as August last year. Commentators infer the worst. Was Lee tricked into the release?

The argument, of course, rests on whether Lee had the capacity to make such a decision.

On Mockingbird’s penultimate page Lee’s narrator, Scout, announces that she feels “very old”. Scout is a mere seven years of age but the implication is that the weight of her experience dwarfs her years. Harper Lee has felt similarly old, at least in the public imagination, for a long time. She published 'Mockingbird' aged 33, but experienced the brunt of fame harder than most. Accusations that 'Mockingbird' was actually the work of her childhood friend Truman Capote, the pressure of a follow-up, and invasions – still ongoing – into her private life quickly followed the novel’s release. Her life itself was subsumed into fiction, make-believe and mythology.

In 2005’s film Capote Lee is depicted as attaining recognition from everyone except the person from whom she seeks it the most: her friend Capote. This, again, is a half truth. In an early letter Capote expressed praise for the novel, though the two writers drifted apart soon after: Lee into careful solitude, Capote into alcohol and drugs – both victims of a kind to their own success.

July 14 offers the next chapter in the lives of Jem, Atticus, and Jean Louise “Scout” Finch. A day of celebration, Cajun chicken and speed-reading, yes – but also a day to reflect on one of the 20th Century’s greatest mystery stories: what became of Harper Lee’s life?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies