'I, too, am Oxford': The intricacies of racism today

Struggling to feel accepted and taken seriously at university, ethnic minority students at Oxford and Harvard have begun to speak out against racism

A few weeks ago, I watched with much difficulty as a friend of mine broke down on a platform at Waterloo station on our way home. Deeply concerned and yet somewhat awe-struck by the image of a grown man in tears (particularly a man of Nigerian descent in a world in which black men are constantly presented as ‘hyper-masculine’ — physical, feral and sexually potent musicians like Tupac and 50 cent or boxer Mike Tyson come to mind) my concern morphed into anger and resentment as I learned the cause of his upset.

This man, who I have always held in the highest esteem, was bawling over his feeling of rejection and isolation within the confines of the elite, majority-white university where he is undertaking a Master’s degree. He explained to me how he felt his knowledge was “devalued” by some of his white classmates on the basis of his skin colour, apparel, gestures, accent and all the other characteristics which differentiate him from most of the class.

He told me his classmates take little interest in his contributions in the classroom, and that they hold assumptions about his point of view as a black male of African descent, assuming what he has to say would be irrelevant to their context and could only be representative of Africa instead. Never mind the universality of issues surrounding public health, the subject of his degree.

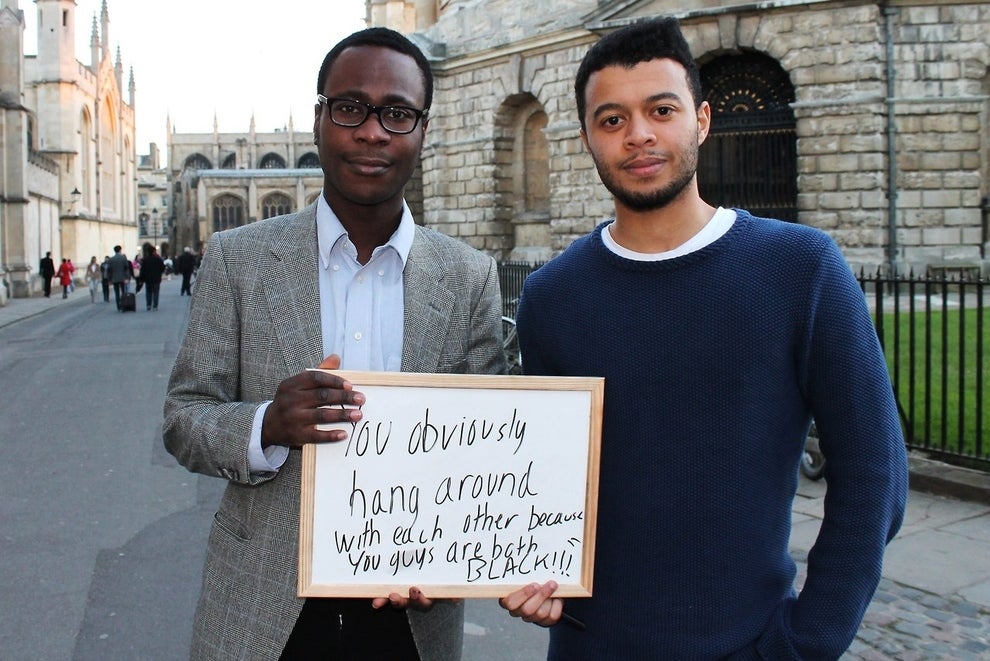

Such attitudes towards ethnic minority and foreign students are prevalent in addition to the “institutional bias” already harboured by some elite education institutes in accepting students from ethnic minority backgrounds. Struggling to feel accepted and taken seriously at university, ethnic minority students at elite institutions like Oxford and Harvard in the US have now begun to rightly speak out against the "othering" which they face. A new project which aims to debunk racist attitudes, highlights the presuppositions some students hold regarding minorities, for example, by assuming that minorities shouldn’t be able to speak English well or that they should have “African” names if black. Such projects are increasingly important to expose the intricacies of racism today.

Aside from seeking to highlight the implications of such presuppositions on the power-knowledge paradigm in classrooms, boardrooms and beyond, I am bringing up this issue in the hopes of offering an insight into one of the myriad ways in which racism manifests structurally in modern British society. In today’s Britain, racism is no longer necessarily obvious, but rather subtle - making it difficult for those who suffer to speak out, as a recent talk at the University College London regarding the lack of black academics in the UK brought to light. Rather than being confined to the colour of one’s skin, the nuances of today’s racism are best understood through more complex presentations of heritage, through language, religion, country of birth, gesture and demeanour and these presentations have become the criteria through which racist judgment is passed.

One report from 2012 states that of a poll of 2,000 adults, over a third admitted to making racist comments. On the other hand, a different report states that the young of Britain are actually overcoming the race issue as the “Jessica Ennis generation” where racism is ceasing to be a major issue by pointing to high levels of interracial marriage which would have been thought implausible just 50 years ago. What these reports fail to recognise is that the parameters of racism are evolving. By continuing to define racism to the blatant and visible, they tend not to factor in the kind of racism which is less apparent– within the immigration laws, inside the HR departments at offices, inside classrooms, admissions offices, boardrooms and within communities themselves.

The “casual racism” of bygone years - where one might pronounce someone as black and declare that the reason to deny them opportunity - may indeed be unthinkable today; and the majority white community may no longer fear the very words “black” and “Asian” anymore, but the fear of difference persists as ever. Perhaps that is why, even in 2009, it was revealed that in the job market, just having a black or Asian name could mean the loss of job opportunity. I myself have watched all my white friends with the same qualifications as me get interviews and jobs as I waited patiently for calls which never came. Black friends of mine have even changed their names to sound more English in the hopes of getting shortlisted. The job market is of course just one of the many places where this new brand of hidden racism continues to stunt the opportunities afforded to minorities in Britain.

While it may be satisfying to gloat about positively changing attitudes towards race in comparison to two decades ago, mulling over notions of a “post-racial” Britain as the national census of 2011 and the reports which were drawn from it seemed to highlight, it would be dangerous to become complacent about addressing the prejudice that minorities contend with. We should work towards exploring racism in British society beyond its occurrence, and into the ways in which the parameters are changing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies