If extremists are those who 'don't identify with Britain', then I'm one of them

As a second-generation immigrant, I'm not inclined to sweep Britain's xenophobic history under the rug

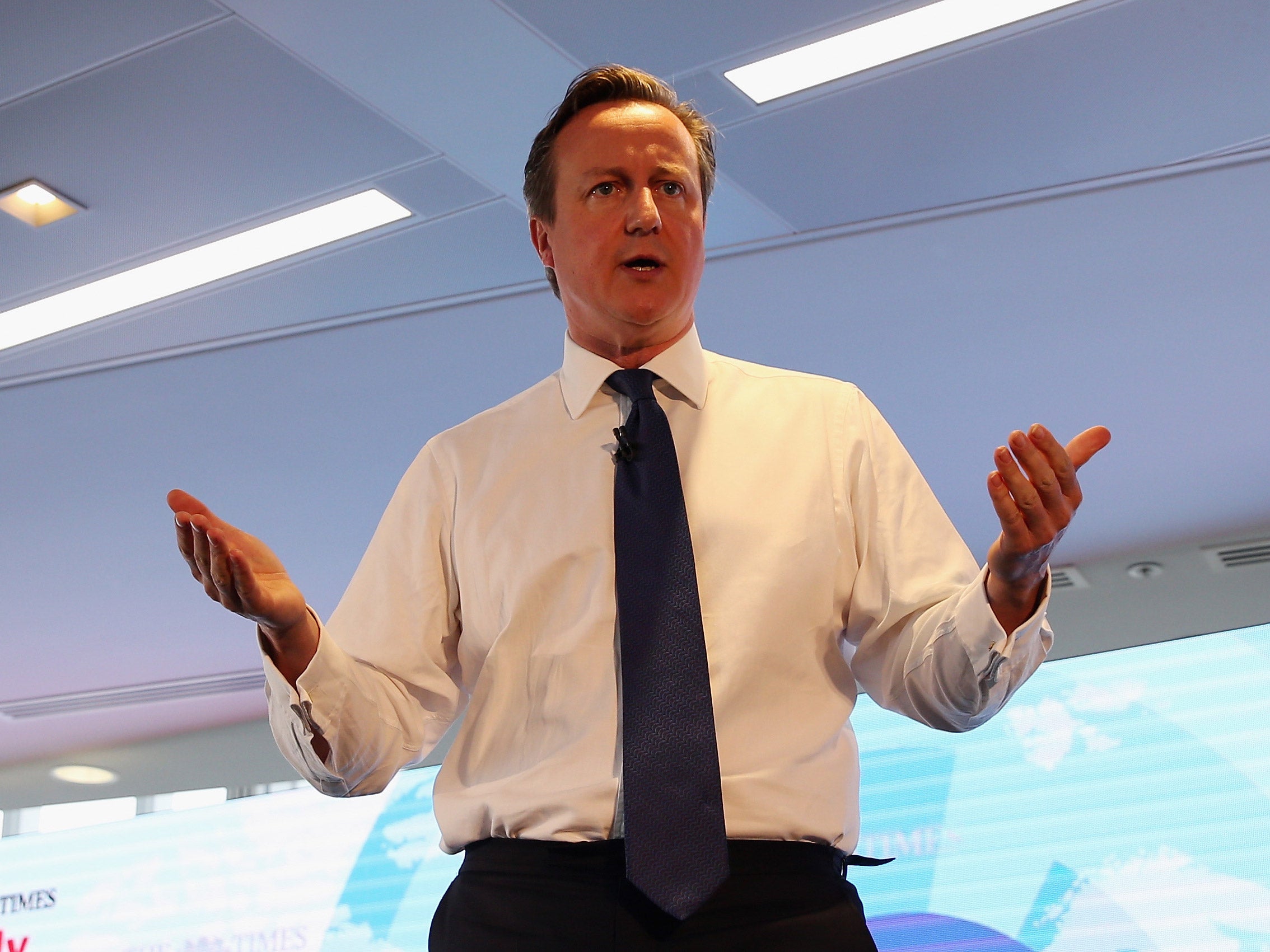

In his speech on extremism yesterday, David Cameron challenged us to “confront a tragic truth - that there are people born and raised in this country who don’t really identify with Britain”. Well, at the risk of winding up in Belmarsh, I have a small confession to make. I’m one of them.

As a second-generation immigrant with roots in the global south, there are numerous reasons for me not to self-identify as British. For a start, I have no wish to negate or even subordinate the important part of my background that is non-British. There are positive reasons for that, but also negative ones, namely the distinct lack of a warm welcome that immigrants and their families have received in this country over the years.

I understand why some of us feel the need, even the pressure, to proclaim our Britishness and express gratitude for being able to live here. But I’m personally not inclined to sweep decades of racism and xenophobia – expressed structurally, verbally and physically – under the rug in the interests of fitting in. These problems are not aberrational but endemic aspects of the country that Cameron instructs us to love, where immigrants and minorities continue to be scapegoated by Fleet Street, Westminster and many members of the public.

Another problem lies in how we define this allegedly wonderful thing called Britain. The Daily Mail attacked Ed Miliband’s late father as the “Man Who Hated Britain” because he opposed the country’s dominant institutions and the national status quo more generally. If this is the definition then once again, I fail the test.

Britain’s wealth and power was built in no small part on the epic crime of imperialism and the holocaust of Atlantic slavery. Today, our Anglo-American economic model has made ours one of the most unequal of the rich societies and, as a result of that, placed us close to bottom of the rankings across several measures of social wellbeing. Abroad, while the British state boasts of its liberal democratic nature, it helps to deny those same rights to the subjects of some of the nastiest regimes on earth, in its capacity as a world-leading arms dealer.

Perhaps worst of all, the industrial capitalist model that is British power’s historic gift to humanity is now cooking the planet, creating the prospect of a hellish future that our current government seems intensely relaxed about. All in all, demanding that people take national pride this legacy strikes me as a little extreme.

What if I put aside the Mail’s authoritarian notion that love of Britain means deference to the existing order, and instead look at the country as a whole? How can a nation of 60 million people, full of complexities, conflicts and contradictions, the good, the bad, and the indifferent, possibly be boiled down into something singular that one can meaningfully identify with? The government classifies extremism as a rejection of ‘British values’, but how do we decide whose values these are? Are they mine or David Cameron’s? Lenny Henry’s or Nigel Farage’s? Ralph Miliband’s or Paul Dacre’s?

It is time that we stopped treating patriotism as a self-evidently good thing, and instead recognised it as an irrational form of conceit, one that is especially unhelpful in political discussion, where we need to make honest, critical assessments of what is done in the name of our country. For example, rather than congratulate ourselves on our national love of liberty, we might reflect instead on the effects of decades spent lavishing material support on various autocratic regimes of the Middle East.

It is these elites who have driven the entire region into a socio-political cul-de-sac whose end is the panorama of civil conflict and state collapse that has given rise to the nightmare of ISIS. Through decades of backing for those regimes, and through its own military interventions, Britain has contributed significantly to this process. Facing up to these realities could form part of a more modest, fact-based and fruitful approach to the issue of terrorism than the one set out by the Prime Minister yesterday, which amounted to little more than wrapping himself in the Union Jack, and declaring that the cause of extremism is extremism.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies